Wednesday, December 12, 2012

The Lyceum is the University of Mississippi’s main administrative building. Constructed in 1848, the building housed a Confederate hospital during the Civil War and served as headquarters for federal troops when a riot erupted in 1962 over the enrollment of the first black student, James Meredith. Photo by Trip Burns.

On Nov. 6, Don Cole saw history repeating itself.

It was already a historic night. At around 11 p.m., the nation’s first African American president won a second term. The coalition of voters that made Barack Obama’s victory possible, among them African Americans and other ethnic minorities and college students, rejoiced at what sometimes seemed like an implausible victory.

The University of Mississippi in Oxford was no exception. Emboldened by Obama’s win, black students took to the campus’ streets in celebration. A small group of them, maybe 50 or so, taunted white classmates who, judging by their unhappy faces captured on widely distributed cell phone videos, preferred Obama’s rival, former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney.

It didn’t take long for black students to be reminded that they were still in Mississippi, and at Ole Miss.

Whites came out in droves from dormitories and off-campus locales to express their displeasure with the election results. Many packed into cars and pickups whose stereos blared “Dixie” and whose passengers declared that the South would rise again. The image of a group of young white men gleefully watching an Obama/Biden campaign sign burn would become the most enduring image of the night.

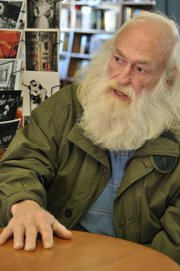

Cole, 62, who works at the university and lives in Oxford, was all too familiar with the sight of the campus in upheaval over the audacity of African Americans. Similar dramas have played out for years at Ole Miss, which today has a student population of 16,586, about 17 percent of whom are black. (Oxford, the tony town in which the university is situated, has 19,400 residents; 20 percent are black).

Before election night, Cole saw it nine years earlier when the university dumped its controversial Colonel Reb mascot. Cole saw it in the 1980s when a black cheerleader refused to carry the Rebel flag. Cole was all too familiar with the famous story of a cocky 29-year-old Air Force veteran named James Meredith, the impetus for a deadly riot when he stepped onto campus and into history books as the first black person to enroll at Ole Miss.

Cole had a starring role in the drama as an Ole Miss student in 1970, which resulted in his dismissal from the institution and started him on a decades-long odyssey through four states before he returned to Oxford in the early 1990s.

“Of all the people who were disgruntled and hurt and felt their work had been undone, I lead that pack,” Cole said of the election-night protest, which is currently under review by a panel that is attempting to reconstruct what happened.

“I saw years of work of digging out of this hole covered back up. I felt quite disgusted, and there are still some feelings there of discontent even today.”

Cole describes the main players on election night as a young, immature few, but he recognizes that their actions likely caused irreparable harm to Ole Miss’—and to a lesser degree, Oxford’s—already dubious reputation with respect to race relations.

That story goes back to the school’s origins in 1848 and its founding trustees, who were among the state’s most eminent scholars, politicians and slave-owning planters who saw the perpetuation of slavery as vital an institution as the university they governed.

Its nickname hearkens to the antebellum period when slaves referred to planters’ wives and daughters as “ol’ miss.” Colonel Reb, its revered mascot, is a crazy old officer in the vanquished Confederate army.

“I know the history of this place well and, to a great extent, I’m a part of the history of this place. Much of what the recent event unveiled was not too much different than anywhere else, but because it’s here, because of our history, because of the hole that we dug for ourselves, it’s magnified,” Cole said.

But Cole, who is African American, embraces the complexity of the history he shares with Ole Miss and Mississippi. “It’s a contradictory type of place,” he says.

Mississippi Microcosm

That contradiction is rooted in the university’s 1844 charter. Located in the north Mississippi hills of Oxford, it is the oldest public university in the state and its flagship. The school’s first matriculates were the sons of plantation owners and, when women began attending the school after the Civil War, it literally became a breeding ground for the South’s moneyed elite.

In that sense, Ole Miss has always been a microcosm of Mississippi. The concentrated wealth and promise that Ole Miss represents stands in contrast to the bleak reality the vast majority of Mississippi’s citizens have long faced.

As the university boasts annual recognition from national magazines for the hotness of its sorority girls and the pleasing aesthetics of its manicured lawns and Greek revival structures, Mississippi remains the nation’s poorest state with the most dismal health and educational outcomes.

Ole Miss is also the proving ground for a southern political cabal, the tentacles of which stretch to Jackson, Washington, D.C., and beyond. Curtis Wilkie, a historian, Ole Miss journalism professor and alumnus, wrote of the university in 2010: “The school had a pull on young people in Mississippi. For anyone interested in building connections, Ole Miss served as a valuable starting place. To those attracted to politics or the law, the school seemed essential to their curriculum vitae.”

The accuracy of Wilkie’s observation is evident when reviewing the extensive roster of Mississippi politicians and captains of industry. Ten of the last 11 Mississippi governors graduated from Ole Miss or its law school—one of two in the state—along with scores of statewide constitutional officers, congressmen, and state lawmakers and business leaders.

That list, too, is fraught with contradictions. While former Gov. Ross Barnett expanded the role of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a clandestine organization the Legislation created to spy on Mississippi’s citizens involved with the Civil Rights Movement, and refused to admit James Meredith until threatened with the largess of the U.S. military, Gov. Bill Waller dismantled the commission when he took office in 1972. Later, Gov. William Winter’s work on education and racial reconciliation earned him an institute at Ole Miss named in his honor.

In his book “The Fall of the House of Zeus,” Wilkie chronicles the unlikely relationship between Oxford attorney Richard Scruggs, a Democratic Party fundraiser, and his brother-in-law and fellow Ole Miss alumnus Republican U.S. Sen. Trent Lott.

Of course, building alumni ties is the whole point of college. But the way Ole Miss wields influence seems less meritorious alumni network than nepotistic secret society, more Skull and Bones than Phi Beta Kappa.

Busting up that good ol’ boys’ club is the thing that compelled James Meredith to enroll at Ole Miss, an act that has become the centerpiece of hundreds of books, documentary films and news stories about the Mississippi story.

Often with Ole Miss’ powerful graduates in the director’s role, race has been the main narrative thread in that drama. That tale includes slavery’s role in Mississippi’s ascent to the nation’s wealthiest state before the Civil War and its secession from the union to keep its numerous slaves subjugated and, thus, its riches intact. Then, after slavery’s destruction, its descent to the nation’s poorest state, where it has since remained. It also includes serving as the stage for the most dramatic scenes of the civil rights era, including the Meredith-inspired riot of 1962.

Throughout his life, Meredith has said he wasn’t concerned with blacks and whites eating side-by-side in the cafeteria.

“The University of Mississippi wasn’t my main target. My main target was the state of Mississippi. The university turned out to be the most vulnerable spot to attack the enemy. I was going after the enemy’s most sacred and revered stronghold.

“My application to Ole Miss had little to do with ‘integration’ but was made to enjoy the rights of citizenship, and by doing that, to put a symbolic bullet in the head of the beast of white supremacy,” Meredith writes in his 2012 memoir “A Mission from God.”

When Don Cole arrived as a proud freshman in 1968, less than seven years after Meredith, he was surprised how little progress had been made on the race issue. Whites still greatly outnumbered their black counterparts, and made sure the black students knew it.

White males, for example, would block sidewalks when black students approached. The young women were more subtle, preferring to convey their contempt by wearing scowls and brandishing small Confederate battle flags, Cole said.

On the evening of Feb. 25, 1970, Cole and half the black students marched onto the stage during a concert at Fulton Chapel and raised their fists into the air. The demonstration was the culmination of two years worth of demands from African Americans that the university recruit more black students, faculty and professional staff, and to address acts of harassment from their white peers and hostility from employees of the university.

In the days leading up to the Fulton Chapel protest, blacks had engaged in a number of acts of civil disobedience. The previous evening, some black students danced on tables in the cafeteria to the music of Mississippi native son and bluesman B.B. King. Another cadre of Black Student Union members marched to the home of Chancellor Porter Fortune, who arrived in 1968 from the University of Southern Mississippi. Fortune had permitted the BSU’s formation so African Americans could have a formal vehicle to voice their concerns, and he was not pleased that members of the organization were now standing on his front lawn.

That black students felt comfortable enough to publicly antagonize officials at the same university that drew white racists from far-flung parts of the nation to make an attempt on James Meredith’s life could have been interpreted as a sign of tremendous progress.

Blacks didn’t see things that way.

Mary Givhan (nee Thompson), who grew up in Oxford and was a freshman when she participated in the protest, recognized that the students’ protest was a bold move. Perhaps caught up in the general mood of the time, Givhan and others believed they had no choice. While whites seemed resigned that black students on campus was now a fact of life, the fact that the administration wasn’t doing more outreach to make African Americans feel like part of the campus community angered Givhan, Cole and other blacks.

“As far as opening up admissions for black students, yeah, that was done,” Givhan said. “But there was really nothing else done to make it a welcoming and inclusive environment.”

The Slavery Question

In some sense, the roots of the Fulton Chapel protest did not begin with James Meredith or even the founding of the University of Mississippi.

Before whites controlled the land, it belonged to the Chickasaw Indians. On Oct. 20, 1832, the Chickasaw ceded their tribal lands east of the Mississippi River to the United States to find a new home in the West.

The government outlined its rationale for relocating the indigenous people in the preamble of the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek, which states: “Being ignorant of the language and laws of the white man, they cannot understand or obey them. Rather than submit to this great evil, they prefer to seek a home in the west, where they may live and be governed by their own laws.”

President Andrew Jackson, believing the Chickasaw would never be happy or prosper under white rule, dispatched his Commissioner General John Coffee to make the deal for 6,283,804 acres in the Red Clay Hills of northern Mississippi. The immense parcel included present-day Lafayette (pronounced luh-FAY-et) County and the town of Oxford.

The pioneers named the fledgling municipality after the English town and university whose origins date to the 11th century, hoping to erect an American university to rival its namesake.

Even though most crops can grow in the dense soil and moist semi-tropical weather with long, hot summers and short, cool winters, Oxford’s founders eschewed basing the city’s economy on heavy agriculture. Because Oxford didn’t rely on farming, it didn’t require the large numbers of African American slaves who were abundant throughout the Delta’s fertile alluvial plains and other parts of the state. Today, Oxford’s black population is 20 percent compared to the 37 percent of African Americans who represent Mississippi.

The Mississippi Legislature agreed to form a university in January 1841, but did not designate a location. Contenders included Brandon, Kosciusko, Louisville, Middleton, Monroe Missionary Station, Mississippi City, near the Gulf Coast in the southern region of the state, and Oxford. Oxford’s one-vote margin of victory was so contentious that a small cadre of lawmakers from Adams and Wilkinson Counties flirted with seceding from Mississippi.

A who’s who of Mississippi gentility formed the original Board of Trustees, which met for the first time in Jackson on Jan. 15, 1845, and included wealthy planters, future Mississippi governors and key figures of the future Confederacy.

Most of the trustees, picked from state’s various regions, held vast tracts of land and some held slaves. This included one of the university’s first presidents, F.A.P. Barnard. Barnard, who later become president of present-day Columbia University and was the namesake for Barnard College, was a northerner who had studied at Yale and had misgivings about having slaves.

It wouldn’t be long before the brand new chancellor and university would grapple with its first race scandal, which historian David G. Sansing outlines in his book “The University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History.”

After attending a convention in Vicksburg, Barnard and his wife returned home to the news that two university students had raped and badly beaten their 29-year-old house slave named Jane. A witness identified the students as J.P. Furniss and Samuel B. Humphreys. Jane identified Humphreys as the rapist.

Barnard wanted the boy brought to justice, but the law barred slaves from testifying against whites. Barnard’s efforts to defend his slave soon drew murmurs and an all-out smear campaign that charged the northern-born Barnard was insufficiently resolute in his support.

Questioning a man’s commitment to slavery was a serious charge in the years that preceded the Civil War, and Barnard knew that appearing unsound could irreparably tarnish his reputation.

At the conclusion of a two-day long hearing that had the feel of a trial, Barnard pronounced, dishonestly, that he was “as sound on the slavery question” as every member of the board of trustees that served as his jury.

In the years leading up to the war, whites were so afraid of slave rebellions, such as the massacre John Brown led at Harpers Ferry, that slaveholders reined in their chattel. One university trustee, A.H. Hamilton, had previously encouraged his slaves to learn to read and write, but reversed course and forbade the practice.

The national drama over the slavery question was starting to play out in Oxford.

Ups and Downs

After the 1970 Fulton demonstration, drama was just starting to play in Don Cole’s life. The Fulton Chapel protest was orchestrated to take place during a performance of Up With People, a racially diverse band that toured internationally. The Black Student Union thought the demonstration would thrust Ole Miss’ treatment of black students into the limelight for the first time since James Meredith graduated in 1963.

After the a brief moment on stage with the band, black students left the stage and exited the chapel where they encountered Mississippi Highway Patrol officers waiting to arrest the demonstrators.

Cole went to the Oxford city jail. When it filled up, the remaining protesters were shuttled to Parchman, home to Mississippi State Penitentiary. A photographer from the student newspaper, The Daily Mississippian, covered the event and snapped pictures of the black students who marched on the stage. Ole Miss commenced dismissal proceedings of Cole and others identified in the photographs.

He maintained a defiant disposition through the process, knowing what the outcome would be. M.M. Roberts, president of the Board of Trustees of State Institutions of Higher Learning, which oversaw the students’ final appeal, made no secret of his hostility toward blacks and frequently called the students n-ggers during the hearings.

Roberts had previously represented a Forrest County circuit clerk who was the first southerner charged with discrimination under the federal Civil Rights Act. Roberts was also a member of the Forrest County Citizens Council—a group of white businessmen and civic leaders formed to defend segregation—and is the namesake for the University of Southern Mississippi’s football stadium.

“We went in with a certain amount of arrogance toward the university, and if we thought we were going to get off, we would have gone in a little more humble than we did,” Cole said. “We knew our fate was sealed.”

That was a dark period in Cole’s life. He and his best friend landed in Gary, Ind., working at a steel mill. Cole applied to several universities, but none would admit him, and he eventually quit trying. A bookish fellow, Cole hated being a steel worker.

“I was making good money, but the job was not satisfying. I wanted a higher level of conversation. I didn’t want to be ashamed to talk about a book I’d read,” Cole said.

Meanwhile, things were looking up for Cole’s classmate Mary Givhan. Givhan had grown up in Oxford and chose to attend Ole Miss to be closer to her family instead of Tougaloo College in Jackson and, more simply, because it was her right to do so.

After she graduated with a degree in business in 1973, Givhan became one of the first African Americans to work in the university’s financial aid and admissions department. She oversaw recruiting at African American and poor white high schools around Mississippi, and her charge was to be a walking counterpoint to the prevailing orthodoxy that you had to be a rich white kid to get into Ole Miss.

Givhan understood all too well. Having grown up near the university and, despite the fact that her mother worked there as maid in one of the female residence halls, Ole Miss retained an aura of mystery. Among Oxford’s black residents, who mostly worked as laborers and domestic help, Ole Miss was a bit exclusive. For them, having a university job carried almost as much cachet as attending the school did for whites.

So Givhan didn’t need a script when she found herself talking to high-school seniors; she had something more effective: “My face was the company line. It was me standing up there to say, ‘You, too, can make it Ole Miss,” she said.

It helped that the number of black students had now grown into the hundreds. Athletics, at last integrated, also had a racial sensitizing effect on the student body.

In 1970, Ole Miss became one of the last Southeastern Conference schools to integrate its varsity sports teams. In February of that year, Coolidge Ball, a sturdy prospective forward from Indianola, visited campus for a game against SEC powerhouse Kentucky.

When they made their pitch to Ball and his parents, Ole Miss coaches confessed that they had been trying to recruit black players for some time, but none wanted to play there because of the school’s turbulent history with deconstructing race barriers.

So Ball decided to use the Kentucky game to gauge whether he would fit in. At halftime, the public address announcer introduced Ball and a white recruit from Louisiana (the National Collegiate Athletics Association now forbids the practice of introducing prospects at sporting matches). Ball drew greater applause than the white recruit.

“I got such a warm welcome, it stuck in my mind. That was one of my most defined moments. Most defined moments come when you get to the university, but mine came before I got there,” said Ball, who continues to live in Oxford and runs a sign business there.

Before long, the university was integrating in other ways. In 1973, Robert “Ben” Williams joined the football team. In 1976, Peggie Gillom became the first African American on the women’s basketball squad. Gillom is currently an associated head coach for the Lady Rebels.

Phi Beta Sigma, a historically black fraternity founded at Howard University in 1914, became the first black Greek-letter organization to have a house on campus in 1977. Dr. Lucius Williams joined the university as an assistant to the vice chancellor for academic affairs, becoming Ole Miss’ first black administrator, in 1976. Williams’ arrival was a boon to Cole, who had received a bachelor’s degree from Tougaloo, a master’s degree from the University of Michigan and had started a doctoral program at State University of New York in Buffalo before his application to return to Ole Miss’ landed on Williams’ desk.

Williams forgave Cole’s bad boy behavior of seven years earlier.

“Back in the ’60s, everybody was protesting. America was protesting. I was protesting,” Williams told Cole, who was readmitted to Ole Miss in 1977 and finished his doctorate in mathematics in 1985.

Ole Miss was still protesting in its usual contradictory ways. Despite wide acceptance of black students and athletes, the school proudly displayed vestiges of the war the South fought to keep their ancestors in chains at sporting events and other functions. John Hawkins, Ole Miss’ first black cheerleader, declined to participate in the custom, stating at a 1982 news conference at the Phi Beta Sigma house to which Hawkins belonged: “While I’m an Ole Miss cheerleader, I’m still a black man. It is my choice that I prefer not to wave one.”

Hawkins’ refusal to wave the Dixie flag touched off a firestorm of controversy, which included a Ku Klux Klan rally in Oxford that drew about 450 spectators.

Cole was trying to shake his rabble-rouser reputation that got him tossed from campus 12 years earlier and keep his nose clean but, as an informal adviser to black students, he commended Hawkins on his courage during the first of several battles over Ole Miss symbols.

“They knew a nickel’s worth about that history,” Cole said of Confederate flag supporters.

Then Came Secession

Mississippi joined the Union in 1817 and seceded from it 44 years later, in 1861.

The state prospered and needed black slaves to maintain its robust economy and social arrangement. Mississippi outlined its rationale for defecting in its Articles of Secession, which state: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.”

When the war started, Ole Miss suspended classes because the entire student body went off to fight and die under the Confederate flag. A graveyard of 250 student soldiers now sits on the campus grounds. Cannon attacks damaged many buildings in Oxford, including the Lyceum, which functioned as a hospital during the war, and the Lafayette County Courthouse.

During Reconstruction, Oxford again began to prosper, and the period marked a turning point in the state’s history. White settlers and newly freed blacks took advantage of the new opportunities. An area just off the Square attracted enough African Americans that the section was nicknamed Freedman’s Town. Freedmen erected one of the first black churches in the city, Burns Methodist Episcopal Church in 1869.

Among the newcomers was a white couple from New Albany. Murry and Maude Falkner and their 5-year-old son, William (who added a “u” to the surname), relocated to Oxford in 1902.

It was also during Reconstruction that Mississippi elected its first African American representatives to the state Legislature and to Congress. Then, the Republican Party was the party that ended slavery and worked to help blacks achieve equality after the war—and it was the party of choice for new freedmen. Mississippians elected Hiram Rhodes Revels, a Republican, to the U.S. Senate in 1870 as the first black man to serve in Congress. Isaac D. Shadd and John R. Lynch would each serve as speaker of the Mississippi House. Lynch also served in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Improved conditions for blacks drew the ire of the newly formed Ku Klux Klan, started by a band of disgruntled Confederate soldiers in Pulaski, Tenn. The Klan’s first grand wizard, Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, became the namesake for a Mississippi county—Hattiesburg is now the county seat. Forrest’s grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest II, was born in Oxford in 1871, and would follow in his grandfather’s footsteps to lead the KKK.

The Klan was active in Lafayette County. Klansmen regularly performed night raids to terrorize blacks and Republicans to maintain white supremacy. Michael Newton describes in his book “The Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi: A History” how the Klan slaughtered more 30 blacks because they believed an African American murdered a Klansman named Sam Ragland and injured Ragland’s wife. The same group of Lafayette County Klansmen also tortured a group of blacks accused of theft before the accuser realized he had misplaced the money.

Oxford would not be immune to the Klan’s brand of racial terror. In 1904, an African American bootlegger named Nelse Patton was accused of murdering a white woman and jailed. That night, a lynch mob formed to administer their brand of justice, but the jailer hid the key to Patton’s cell and refused to give the inmate over to the raiders.

W.V. Sullivan, a U.S. senator who was born in Panola and had graduated from the University of Mississippi, led the posse. Members of Sullivan’s mob started chipping away at the jail’s exterior wall and opened up a hole in the cell wall large enough to stick a pistol through and shot Patton, wounding him. When they finished knocking down the wall, the mob dragged Patton to the town square where they hanged him from one of the newly erected electrical poles that delivered the still-new invention of electric power to Oxford.

Sullivan was proud of the part he played, boasting later: “I directed every movement of the mob, and I did everything I could to see that he was lynched.”

Oxford at a Crossroads

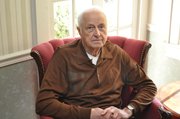

During the chaos of 1962, Ken Wooten was in law school at Ole Miss working in the student-affairs division, and assisted federal marshals and fielded calls from reporters from news outlets around the world.

By the late 1960s, Oxford’s growing pains were almost as acute as the university’s. Eight years after Meredith integrated Ole Miss, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered Oxford—along with the rest of the South—to immediately integrate schools in January 1970.

Arnold Pegues, a lifelong Oxford resident, was in 3rd grade at Johnson-Peterson Elementary School when the schools integrated. In those days, blacks’ only refuge in stormy weather was the public library because merchants would not permit African Americans to stand under their awnings.

“It was a typical southern town. It’s hard to say (racism) was bad because it was the status quo,” Pegues said.

When the court handed down the integration order, some Oxonians feared forcing little white children into classrooms with blacks could touch off an insurrection similar to the revolt that Meredith spurred.

“We didn’t want what happened at the university to happen again. It’s not what we are at this point,” Wooten said of the time.

Wooten helped solicit one representative from every social and civic organization in Oxford, from the Rotary Club and the Garden Club to the Negro Chamber of Commerce and black churches, to pencil out a plan for what integration would look like. The group met at Oxford High School shortly before the Christmas holiday in 1970, which commenced a week earlier than planned.

For high school, blacks attended the Oxford Training School, which represented a challenge because the school was run-down compared to Oxford High School, and white teachers might protest having to teaching there.

Volunteers solicited donations from local hardware stores and repaired old windows and broken doors, painted the building and scrubbed floors. Wooten said they made OTS the showpiece of the district. When the winter term started after an extended five-week Christmas vacation, Wooten said there wasn’t a single incident.

That, he said, showed progress. “You had faced in 1962 a mob of people that was burning cars and shooting and killing and maiming people to no incident in the space of eight years,” he said.

“Of course, the public-school integration was all local people. I guess we were crossing our fingers. There’s always the possibility that there are radicals everywhere and anywhere.”

Transcending Race

After an eight-year stint at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee, former radical Don Cole took another job at Ole Miss in 1993. Ole Miss during the 1990s and early 2000s saw the same pattern with race relations it had followed since Cole was a student: complicated.

In February 2000, a shade less than 40 years after Meredith, the student body elected its first African American president of the Associated Student Body. Not everyone received Nic Lott with open arms, though. Black students grumbled among themselves that Lott only won election because of his light complexion and conservative Republican political leanings that whites found non-threatening.

“(Being Republican) certainly helped build a campaign staff and team to launch my campaign for being student body president, but anyone who would say I only won because I was a Republican would have to totally ignore the coalition we built,” said Lott, who lives in Jackson and works in state government.

At the time, Lott chaired Mississippi College Republicans and said the Black Student Union, College Democrats, International Student Organization, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered organization or their leaders endorsed his candidacy.

Chancellor Robert Khayat, an Ole Miss grad and himself a former Colonel Reb, saw Lott’s election as demonstrative of the strides the school had made. Khayat told the Associated Press in early 2000: “The election (of Lott) confirms that our students have transcended the issue of race.”

Students challenged Khayat’s assertion, though. A spate of racially charged incidents, all occurring around the time of Lott’s election, took place at Garland-Hedleston-Mayes residence hall complex. In late January, a Black History Month bulletin board in the lobby was ripped down. The display was reposted but was torn down again, this time replaced with a poster depicting a monkey and a Confederate flag.

A week later, a bathroom wall was defaced with slurs. About a week after that, the hall director had two football-sized pieces of asphalt thrown through his apartment window. A note with slurs scrawled on it was left next to one of the rocks.

“There was a lot of tension,” said C.J. Rhodes, a Hazlehurst native who entered Ole Miss in the fall of 2000 and was involved in student government.

Two years later, on Nov. 6, 2002, a pair of students discovered slurs and images of nooses on their dorm-room doors and in the elevator at Kincannon Residence Hall, a high-rise dorm that sits on a hill. The incident, which occurred around the time the university was celebrating the 40th anniversary of Meredith’s integration that fall, drew national media coverage.

When three black students confessed, it put the administration, which had vowed to expel the responsible parties, in a prickly spot and enraged campus activists who said the Kincannon incident illustrated the need for hate-crime legislation.

“Why would you do something that foolish and foolhardy and take something that serious and make it into a joke?” said Jason Thompson, a Jackson businessman and musician who was a student at the time.

“I was pissed,” Rhodes said. “I was pissed that these kids would not appreciate what that word n-gger meant and what it would do to inflame this university.”

Lott and Rhodes give Khayat credit for moving the university forward.

In 1997, Khayat got rid of the Confederate flag that had blanketed Ole Miss sporting events by banning the wooden flag sticks, ostensibly for safety. Khayat would make another controversial move a couple of years later that he thought would improve the school’s image even more.

Khayat announced in 2003 that Colonel Reb, the Confederate throwback adopted as the official mascot in 1979 but whose image had been around since the 1930s, would no longer be a staple of Ole Miss on-field matchups. Khayat’s public reasoning was that having “a 19th century person representing a 21st century university in such a highly visible role” seemed odd.

A group called the Colonel Reb Foundation formed to reinstate the old mascot. Efforts included an advertising blitz urging students to reject developing a new mascot. In 2010, after the school gave students the choice between a new mascot and no mascot at all, the Rebel Black Bear replaced Colonel Reb as the official on-field symbol of Ole Miss. The university retains the trademark to the colonel’s likeness.

“The chancellor faced a lot of challenges and opposition. People were kicking and screaming and he led us through that time to make a degree from the university worth a whole lot more,” said Lott, who believes removing the controversial symbols added value to an Ole Miss diploma. “We need to make sure that people who receive this degree are respected just as much as anybody else.”

In 2009, under new Chancellor Dan Jones, Ole Miss instructed its band to shorten the song “From Dixie With Love,” to discourage students from chanting the last line of the song—”the South will rise again.”

In response, a handful of members of the Ku Klux Klan participated in a small demonstration on the steps of Fulton Chapel, where Don Cole and his comrades were placed under arrest four decades earlier, as about 250 people jeered at the Klan’s presence.

The mascot and song remain touchy subjects with many whites in Mississippi and throughout the South who do not grasp the significance of the symbols, and why blacks find them offensive.

“You always had two different conversations. You have the conversation about this is heritage, this is tradition. Then you have the conversation that this is offensive, and those two groups never met,” Jason Thompson said.

Rhodes, now the pastor of Mt. Helm Baptist Church in Jackson, said the symbol controversies and 2012 election-night protests demonstrate that despite Ole Miss’ steps ahead, an ethos of white supremacy remains on the campus.

“I don’t know that the university has really come to terms with what’s in the DNA of the school,” Rhodes said.

“I mean, you can change symbols, you can get rid of the Confederate flag, you can tone down playing ‘Dixie.’ All that has happened, and thankfully so, but what I would like to see is for this flagship institution to lead the way in transforming the systemic, political and economic issues that face our state, and name forcefully how race is the reason why Mississippi is at the bottom.

“At some point, the school has to be courageous enough to say we can’t just talk about being the New South. If we were the epicenter of intellectual white supremacy, we now must be the epicenter of a new kind of intellectual ethic. We’ve got to start to train a whole new crop of leaders to understand that if we don’t become a more equitable state, we’ll continue to be at the bottom.”

Picking Up the Pieces

Twenty-four years have passed since Ole Miss expelled Don Cole for going up against the establishment. Today, he’s part of it: He is an assistant provost for minority affairs and an aide to Chancellor Dan Jones.

“Many individuals said and often say they didn’t understand why I didn’t have any animosity for the place, but I came in loving the place and always did. How can you hate bricks and mortar? How can you hate a building? I might not like the name of it, but I had no animosity,” Cole said in a recent telephone interview.

He watched the election-night protests unfold with disgust as years of hard work to reshape the school’s image unraveled.

The Obama protest followed a year of historic milestones. In March, Kimbrely Dandridge became the first black woman and fourth African American elected as student body president.

On Oct. 1, the university marked the 50th anniversary of James Meredith’s integration of the school. Meredith declined to participate in the anniversary, comparing it to the French celebrating Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo.

Meredith, who was present in 2006 for the unveiling of a bronze statue of his likeness near the Lyceum, believes the statue should now be destroyed.

“I have become a piece of art, a tourist attraction, a soothing image on the civil rights tour of the South, a public relations tool for the powers that be at Ole Miss, and a feel-good icon of brotherly love and racial reconciliation, frozen in gentle docility,” Meredith writes in his memoir.

Also in October 2012, the student body elected Courtney Pearson, a pretty, full-figured, dark-skinned woman, as the first black homecoming queen, an honor historically bestowed on white girls.

There were also signs of regression. In August, vandals keyed the word “n-gger” on freshman Jamal Woods’ car and smeared the same word in lotion on Woods’ dorm room door. Officials reassigned Woods to a different residence hall and turned the case over to the FBI, which launched an investigation. An Oct. 26 campus alert notified students of a black male suspected of committing a strong-armed robbery on campus, reportedly of two white women.

When Nov. 6, 2012, came, the stage was set for something big to happen. Jeremy Holliday, a junior from Tupelo, headed to campus when heard the reports of a campus disturbance and found a parade of cars filled with whites playing “Dixie” and a group of about 100 black and white students causing a ruckus in front of Kincannon Hall. Another 300 students stood around the perimeter, and at one point he thought he heard a gunshot that turned out to be fireworks.

“Did I think it was about to escalate? Yes,” Holliday said. “Did I think there were about to be some fights? Absolutely. Any time someone screams ‘F the n-gger’ and ‘Death to the n-gger,’ and you’ve got a group of black kids outside and a group of white kids outside, absolutely you think something’s about to go down.”

At the end of the night, police had arrested two people, and no one was injured. The following night, a candlelight march to the Lyceum organized by the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, housed at Ole Miss, drew a crowd of 700 students—seven times the number of protesters from the night before.

Chancellor Jones convened a panel of faculty and students to investigate what happened and will issue its findings in a report.

In Holliday’s estimation, Ole Miss needs to do a better job of educating students about race and examine itself on a deep, molecular level. Holliday, who is black, suggests assigning freshmen to read Randall Kennedy’s 2003 book “Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word.”

After election night, he said, too many of his classmates’ anger was misplaced. Instead of being upset about what happened, they focused on the media’s characterization of the incident as a riot after students began using the Twitter hashtag #olemissriot.

“We’re so focused on not calling it a riot. I don’t care what the media says; this is home for us as students. This is the place that we’re associated with and the place we pay to go school and receive an education, so we need to concentrate on making sure that the students are OK and how to make this not happen again,” Holliday said.

“Ole Miss was not the only school that protested President Obama’s re-election, but Ole Miss is the only school that ends up on worldwide news for protesting because we are the University of Mississippi. So therefore, we have to be more careful because people look at us through a microscope.”

Cole said it’s easy to criticize Ole Miss for its history of intolerance, but he believes it’s up to all Mississippians to work toward the institution’s improvement.

“If I give up on it, then my tax money and your tax money is still going to be going there,” Cole said. “And the lower (Ole Miss) is, the lower we all are, so I’m going to be here building it up, picking up the pieces.”