Wednesday, March 14, 2012

I sensed trouble as my brother's three sons and wife slunk out of the room slowly, without making eye contact. It had started well enough. I was in town and hadn't seen my brother or his family for a few months, and they had invited me over for dinner. There had been some cryptic remarks from my sister-in-law concerning the fact that I had told my brother that we had two relatives, great-uncles they would be, who had fought in the Civil War. They were sons of an Irishman who had immigrated to the United States in the early 1800s.

My brother, Will, had asked if I would like to see the research he had on the Breen brothers. Instantly, a chill had set in the atmosphere. I could tell that the question was significant as Will's family was sitting tensely on the edge of their seats awaiting my response. But my little brother looked at me so pleadingly with big puppy-dog eyes that I blithely answered, "Sure."

I understood the family's reaction a few minutes later when Will re-entered the room with an enormous stack of notebooks, pictures, books, maps and other papers. He proceeded enthusiastically—barely taking a breath over the next several hours—to relate the Breen brothers' Civil War experience to me.

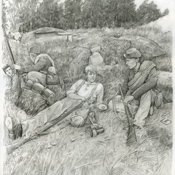

William and John Breen reunited about 8:30 p.m. July 2, 1863, on Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg.

Look closely at the drawing Will commissioned of the event. William's pack (left) has the insignia of the 32nd Massachusetts and on John's pouch the 9th Massachusetts. William's pants and canteen have bullet holes in them from fighting all day in the wheat field. John Breen is in his marching gear, as the 9th had just arrived at Little Round Top. John has a bedroll instead of a knapsack; he apparently cast it off during the long march up from Virginia. His records show the army charged him $2.14 for his knapsack after the Gettysburg campaign. If you look very close to the upper left side of Haslett's Battery, you will see Col. Guirney of the ninth on horseback.

Much like my brother's rediscovery of our two Irish kinsmen, St. Patrick's Day always reminds me of my Irish heritage. Ireland has 6 million Irish people, but 35 million Americans think they are Irish, and I am one of them. The entire linage on my mother's side of the family hailed from Ireland.

My grandmother was a first-generation Irish American—her father emigrated from Ireland around 1900. She was a sweet woman, but hated the British and was an Irish Republican Army supporter. Most of us have forgotten the bloody sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants that defined Northern Ireland for many years. I remember going to some St. Patrick's Day parades in my youth that were scary places to be.

Although parades in Northern Ireland were celebratory for the most part, floats and marchers always reflected both sides of the conflict. Participants hung British soldiers in bloody effigy, and death's head-wearing revelers followed by taunting Catholics.

My brother pointed out that the Breens fought in nearly every major engagement in the eastern theater of the war. Hauntingly, though, it did not go well for either of them. William was captured late in the war and died miserably of exposure in a prison camp. John was wounded in the battle of Spotsylvania and spent the rest of his life with a mangled arm.

Listening to my brother, my mind jumped to the present and to my two nephews. Both are Marines, and both have served two tours of duty in Iraq. Neither came back the boys they were when they left. In my mind, the Breen brothers are linked across the centuries with the Coupe cousins by their shared sacrifice of youth and innocence.

The Irish have given hope to the modern world. Somehow, some way, wiser heads were able to prevail in Northern Ireland—the bloody violence has halted, and peace reigns. Will the same hold for Iraq and Afghanistan? Only time will tell.

The Breen brothers were not heroes in the classic sense. Neither led a desperate charge to halt the enemy advance, nor did they win any medals for bravery. But heroes they are nonetheless, because when duty called, they answered. The same goes for my nephews. I remember roughhousing with them when they were young boys. (One claims his earliest memory is of me dangling him by his feet from a balcony over a barbecue—that can't be.) They are now men and heroes in my eyes.

As we celebrate St. Paddy's Day this year, wearing green and drinking beers, as we catch and fight over superfluous trinkets and thrown beads, it would do us well to remind ourselves of the sacrifices necessary for justice and peace in this world, and of those men and women who willingly do their duty when called.