Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Young Jackson Public Schools scholars returned to classrooms last week. And whether Aug. 8 marked the first time riding a big, yellow bus or the final year of locker assignments, the students will all share one thing this year with every other public-school student in Mississippi: Common Core State Standards.

Variously hailed as the Next Big Thing in education or decried as just another in a long line of high-stakes, test-based reforms that won't work, the Common Core aims to re-establish the United States as a preeminent producer of educated young people.

"When we look at the Common Core State Standards, or college- (and) career-readiness standards, those are more closely aligned to prepare students, when they finish high school, to move into post-secondary study, to move into the workforce," said Nathan Oakley, director of curriculum and instruction at the Mississippi Department of Education.

It's a high bar. Right now, those in higher education complain that many incoming freshmen aren't prepared for college-level work, and employers say new hires don't have basic skills needed to succeed in the workplace. U.S. students once topped the world's educational heap, but that hasn't been true in decades. In comparison with other developed nations, the U.S. ranked "average" in reading, math and science reported the international Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development in 2010.

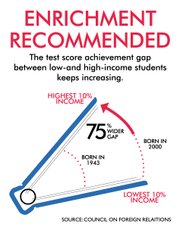

The Council on Foreign Relations noted the country's decline in educational achievement in its June 2013 report, "Remedial Education." Americans who are now between the ages of 55 and 64 have the highest rate of high-school graduation in the world. For the generation aged 25 to 34, the standing has slipped to No. 10.

In 2009, the National Governors Association set out to find a solution. With funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, it hired consultant David Coleman, who assembled a team of 135 fellow consultants, administrators and educators to write a set of standards that, if students reach them, would put us back on top.

A year later, the first two sets of standards—in English-language arts and math for kindergarten through 12th grade—rolled out to "provide a consistent, clear understanding of what students are expected to learn, so teachers and parents know what they need to do to help them," the group's website states.

Mississippi adopted the CCSS in the summer of 2010. In all, 46 states have followed suit. Tests to measure the standards effectiveness in the classroom are in development, and will be available at the end of the 2014-2015 school year.

"I think that there's always something positive and something that's beneficial when new methods, new standards, are implemented ... that can help students," said Carolyn Jolivette, executive director of the Parents for Public Schools Jackson. Problems arise, though, when programs such as CCSS become one-size-fits-all solutions. "We always want the quick fixes," she said. "... We miss part of what the real deal is, and that is: How is this going to affect the children who are going to have to deal with the decisions that adults are making?"

CCSS advocates say that the standards provide a framework to allow teachers to delve more deeply into their subjects, developing students' comprehension and critical-thinking skills over rote memorization. The standards delineate what students should know and what skills they should have at the end of each school year. But the methodology, the specifics of how the schools arrive at those standards, is largely left to the states and to individual school districts.

"The mechanism—the curriculum piece and the materials piece—is determined locally," Oakley said.

Common Core sets high expectations for students, teachers and school districts. Budgeting for new technologies in a time when just putting books in classrooms can be a financial hardship, but high-tech is a reality that schools must prepare students for.

"To deny that education needs to shift, I think, is kind of turning a blind eye to the world we live in," Oakley said.

For students already struggling—and often failing—to reach the old, No Child Left Behind standards, which CCSS replaces, they will see achievement levels drop further with more rigorous standards in place.

"We recognize these standards will require more of our students, and it will take a few years for Mississippi students to master them. States that have already implemented higher standards similar to these and measured their students' performance for the first time saw the number of students scoring proficient drop," states the MDE on its website. "We can expect similar results here in Mississippi. It won't be because our students are any less smart than they were before. It will be because we will be holding them to higher academic standards, which will benefit them and their future."

That the scores will go down isn't surprising. "The question is: What are we going to do with that?" Jolivette asked. She stressed that schools, teachers and students shouldn't be penalized because of the drop. On the other hand, perhaps the deficit model isn't the best one to follow. "It's always about 'what's wrong,'" she said. "It's always about 'these kids' or 'those kids' who are not stepping up to the plate ... and 'those parents' who don't care. ... We never look at what's working and build on that."

MDE has provided professional development for the state's teachers since adopting CCSS. Oakley said he is looking forward to seeing Mississippi's students striving to reach the new standards, and that the main challenge will be how teachers help students who are having problems.

"Focused, individualized attention becomes of paramount importance," he said. "We've got to be targeting instruction to individual students to meet their needs."

What happens before a child walks through the doors at school matters, Jolivette indicated, both good and bad, and no one should expect schools to solve every child's problems. Those solutions must come from the community working together to provide what individual children need to achieve at their best. Nonetheless, at school, she said, "We should educate them, no matter what."

Common Core Samples

From the first grade English-language arts standards:

• Retell stories, including key details, and demonstrate understanding of their central message or lesson.

• Explain major differences between books that tell stories and books that give information, drawing on a wide reading of a range of text types.

• Compare and contrast the adventures and experiences of characters in stories.

From the grade 11-12 English-language arts standards:

• Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

• Analyze multiple interpretations of a story, drama, or poem (e.g., recorded or live production of a play or recorded novel or poetry), evaluating how each version interprets the source text. (Include at least one play by Shakespeare and one play by an American dramatist.)

SOURCE: corestandards.org