Wednesday, January 2, 2013

Rep. Cecil Brown, D-Jackson, was chairman of the House Education Committee for seven years. He believes the most important thing to ensure good education for Mississippi’s children is community involvement in schools. Photo by Trip Burns.

Public-school K-12 education is slated to take a top spot on Mississippi lawmakers' agendas again this year. State representatives and senators will focus the debate on two issues—probably with considerable heat on both sides of the aisle: the Mississippi Adequate Education Program (aka MAEP) and charter schools.

Heat notwithstanding, Republicans will probably get their way on both issues. In the House, Speaker Philip Gunn did some reshuffling of the Education Committee. During the 2012 session, Democrats—with the help of three Republican charter-school opponents—held a slim majority of the 31-member committee; in this year's session, the balance is in the Republicans' favor.

In the last session, Gunn axed long-time chairman Cecil Brown, D-Jackson, and replaced him with committee neophyte Rep. John Moore, R-Brandon. For this session, Gunn removed Democrat Linda Whittington, a strong opponent of charter schools and another long-serving committee member. Her passion for service is reflected in the fact that she takes no salary or per diem from her position in the Legislature.

In her place, Gunn appointed Republican Charles Busby of Pascagoula, a charter-school proponent. Busby narrowly defeated one-term Democrat Brandon Jones—who sat on the education committee—in 2011.

Jones, now chairman of the Mississippi Democratic Trust, accused Gunn of using his speaker's authority inappropriately in replacing Whittington.

"Her removal from the Education Committee over a single policy issue is without precedent and makes clear that the speaker would rather stack the deck than risk losing a straight-up committee vote," Jones said in a statement.

"Issues involving public education in Mississippi deserve a full vetting by our legislators. With this decision, the speaker has ensured that that won't happen here."

Gunn's committee shuffling is within his purview and, in all fairness, Democrats might have done the same if they'd had the chance. Whittington maintained that stacking a committee in this way has never been done before. Republicans gained control of the House in 2011 for the first time since Reconstruction, giving them a majority in both houses of the Legislature in addition to holding every statewide elective position with the exception of the attorney general. If the state GOP was looking for a mandate from voters, that may be as good as it gets.

A Question of Priorities

Viewed from the campaign stump, educating the state's children is high on every politician's wish list for creating Mississippi's economic future. That lofty standing hasn't translated well into allocating actual cash from the state budget, though.

The state's per-pupil spending ($9,708 in 2009) is among the lowest in the nation, reported the Annie E. Casey Foundation in its annual "Kids Count" report. It's nearly half of what the nation's top spenders put into public education and well below the national average of about $11,700 per child.

The state's inability to provide adequate funding is reflected in poor academic performance. In 2011, 45 percent of 4th graders ranked "below basic" for reading; 42 percent of 8th graders were "below basic" in math. Minorities are disproportionately represented in the state's failing education system: The high-school dropout rate for whites in 2010 was 13 percent; for blacks, it's closer to 21 percent, the state Department of Education reports.

"The average student is not getting what he or she needs," Brown said. "... We tend to think that kids are little robots and that they come to school ready to learn. That's just not the real world."

Brown said that Mississippi schools lack the resources for school counselors and health professionals. Kids bring their family issues to school—everything from alcoholism to broken families to domestic violence—and schools can't ignore those issues and just expect the kids to sit quietly and learn.

"The dropout statistics we report aren't accurate. They're not even close," he said, indicating that 36 percent to 40 percent of Mississippi's 8th-graders never make it to graduation. "In Jackson, it's closer to 50 percent."

At the heart of each school district's ability to pay for its public schools are the property taxes paid within the district. Areas where the citizens are less prosperous can't put as much money into their schools as more affluent districts, resulting in an inherently unequal ability to provide quality education to children across the state.

The Mississippi Legislature passed MAEP in 1997 to level the funding playing field for all of the state's children who attend public schools. MAEP is designed to provide poorer districts with additional state funds so that each school district can provide at least an adequate education.

Former Gov. William Winter, who helped usher in the formula, emphasized the fact that it is only designed to provide adequate education, not anything extraordinary. "We would still be last in almost any category," he said. "... There has to be a way to raise the understanding of more citizens in this state of the imperative of investing whatever it takes to raise the quality of education."

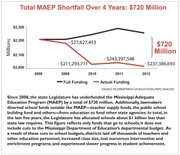

The MAEP concept has not been popular enough in the Legislature to actually provide the money to make it work. In its 10-year existence, lawmakers have only given the program its full due twice, after Hurricane Katrina for the 2006 and 2007 school years, when an influx of federal funds made up the difference.

The Mississippi Department of Education has requested $2.4 billion to fully fund MAEP for the coming school year. If history repeats, the reality is that the Legislature will allocate a figure short of that by some $250 million.

The lack of adequate money has left many of Mississippi's school districts with crumbling buildings, not enough teachers or textbooks, and looking to their district's taxpayers to make up the difference with increases in property and local sales taxes.

"I've got schools up in the Delta where when it rains, you put out buckets, and the kids don't have all their textbooks." Whittington said. "... What are we thinking?"

"Money is a necessity," Brown said. "You can't have schools that don't have money to pay the utility bills. You can't have schools that can't pay teachers." He added that hundreds of teachers across the state have been laid off because schools don't have the funds to pay them. "They have bigger classrooms and fewer teachers. We have school building with sewage backing up in the bathrooms."

One of the factors in figuring the formula is that actual costs from the prior year are used to determine costs for next year. That means low funding in the past translates into low funding for the future, when costs for the 2010-2011 school year determine funding for the 2012-2013 year.

The talk this year is that the Legislature may scrap the formula altogether, but as yet, no proposals have been publicly revealed. State Auditor Stacey Pickering wants to revised the formula to ensure that each school district reports to the state using the same criteria, for example.

"[T]he definitions are not uniform across the state from school district to school district," he told Mississippi Public Broadcasting. "They cannot be audited by federal law, so they shouldn't be in the formula to start with. And we shouldn't be using that to base this much of our state budged on."

House Education Committee Chairman Moore concurred with Pickering. He argued that a lot of the data coming in from the districts was inconsistent.

That includes the way districts count daily attendance, report test scores and how many students are eligible for free lunches.

"If it skews the data even a little bit, districts that need more money are being penalized, and then there are some districts that are getting more money than they deserve," he said, and mentioned Claiborne County as an example. Moore added that the formula should ensure money goes into classrooms and not administrative costs.

"Who's been driving this freight train?" Moore asked rhetorically, saying that he wants to get to the bottom of why the district reporting has been so inconsistent. In the years MAEP has been in place, he added, "no one has ever thought to look at this situation; there's never been any audit. There's never been anyone who questioned this formula."

If the data going in is garbage, the conclusions drawn from it can't be any better, he said. "We want Mississippi to quit being number 50," he said, adding that he would love to see people coming from all over to find out how the state went to No. 1 in education.

Charters This Year?

2013 Key Legislative Dates

Jan. 8 — The Mississippi Legislature convenes at noon

Jan. 16 — The last day for drafting general bills and constitutional amendments

Jan. 21 — Deadline for introduction of general bills and constitutional amendments

Feb. 5 — Deadline for committees to report general bills and constitutional amendments originating own house

Feb. 14 — Deadline for original floor action on general bills and amendments by own house

Feb. 27 — Deadline for revenue and appropriations bills originating in own house

March 5 — Deadline for committees to

report general bills and constitutional amendments originating in other house

March 13 — Deadline for original floor action on general bills and constitutional amendments created in other house

March 19 — Deadline for original floor action on spending bills originating in the other house

March 29 — Deadline for introducing non-revenue local and private bills

March 30 — Deadline to file conference reports on spending bills

April 1 — Deadline for filing conference reports on general bills and deadline for final conference reports on spending bills

April 7 — Sine Die

Privatizing and monetizing public functions have been at the core of conservative policy for decades, and education is no exception. In his 1996 book "Agenda for America: A Republican Direction for the Future" (Regency Publishing Inc.), former Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour hailed charter schools as an important part of public-school choice for parents. He also urged the abolition of the U.S. Department of Education and the end of teacher unions and state certification.

"[C]harter schools encourage innovation and decentralization," he wrote. "By definition, charter schools are 'public' or government-funded schools that are created and operated by a group of teachers, parents or other qualified individuals. These individuals enter into a contractual arrangement with the state or school system and, as long as they prove that they are meeting their contractual agreements with the sate or local district, they operate largely free from state and district supervision."

While still a small part of the huge public-education pie, the numbers of charter schools in the United States are steadily growing. From 1999 to 2009, the number of students enrolled in charter schools jumped from 340,000 to 1.4 million, more than tripling in a decade. In the 10-year period, charter schools went from making up 2 percent of all public schools to 5 percent with about 4,700 schools in the 2008-2009 school year.

Mississippi has had a charter-school law on the books since 1997, but as yet, no charter schools. The dilemma hinges on details: How much supervision should the state give to charter schools, for example.

Part of last year's legislative debate swirled around teacher certifications: The proposed bill stated that state Department of Education certification would only be required for half the teachers in a charter school.

The bill failed to make it out of committee by only one vote.

Opponents say that charter schools will suck precious funds away from public schools, which has occurred in places where charter schools have been enacted. Public money for education goes with the child, but that doesn't account for a district's fixed costs.

"The local and federal money follows the child to the new school," Whittington said. That doesn't reduce costs such as insurance, electricity, the salary for the school principal or the cost of running school bus routes. "It sounds so simple, but it's not."

Parents should not see charter schools as a panacea for what ails education in Mississippi, charter school opponents point out. The record of charter-school successes is mixed: Some are excellent, others failures. Most fare no better or worse than traditional public schools.

"If you give me a well-funded school that has committed teachers and involved parents, I'll give you a good school," Whittington said. "And it doesn't matter if it's charter or not."

The problems go a lot deeper than who controls the money. But even staunch Democrats are willing to give them a try in districts that consistently fail their students.

"We have inherited such a huge economic and social and cultural deficit in Mississippi," Winter said. "We've had such a huge imbalance in the economic well-being of so many people. I guess this is another way of saying that we are still paying the price for having neglected raising opportunities for African Americans. ... The public schools have had imposed on them a burden they cannot meet."

"I think well-conceived and properly run charter schools have a place," Winter added. "I think they may be the answer in some of the poorer (school districts) that seem to be incapable of raising their own standards. But I think charter schools are not the answer. I think they are an answer in certain situations. I think it would be a huge mistake to drain off public funds to set up another set of schools out there."

"What I want the public to understand is that we need to be paying attention right now," Whittington said. "We're about to start taking money away from our public schools, (which) are already underfunded. ... Let's fund public education before we start siphoning (funds) off."

Wait, There's More

In addition to MAEP and charter schools, look for bills this session to legislate teacher merit pay (a favorite of Gov. Phil Bryant) and at least a discussion of pre-K education.

Gov. Winter—who was responsible for enacting statewide kindergarten classes in 1982—said emphatically that a comprehensive, statewide pre-K program is the most important thing the state could do to ensure the future of Mississippi's children—not creating charter schools. That, and teaching parents—who themselves may not have a tradition and culture of learning—the importance of early education.

"The capacity of the brain to absorb learning is maximized in those early 3, 4 and 5 years," Winter said in the interview. "If we miss that opportunity, then it's too late."

Whittington put it a bit more succinctly. "Put the money on the front end," she said. It's cheaper than spending it on incarcerating grownups who can't get jobs and cope.

Moore wants to ensure Mississippi's schools are the best in the country. The most important thing the Legislature can do is to give teachers what they need. "If we give them the resources, I believe they can do the job," he said.

But resources aren't the only thing teachers need. We need to raise our esteem for the profession of teaching to meet the lip service so many have given it, Winter said, as vital educators of our children and the builders of our future.

Ultimately, it has to come back to the local districts to make the difference, Brown said, because that's who hires supervisors, teachers and where children will or won't get a good education.

"The Legislature can't really do anything about educating kids. All of that's done in the schoolhouse," Brown said. "... Until communities get involved in the schools again, until communities where we have failing schools get outraged about the fact that their schools are failing, nothing's going to change."

Comment and email Ronni Mott at [email protected].

CORRECTION: In an earlier version of this story, we mistakenly reported that Rep. Linda Whittington takes no salary or per diem from her position in the Legislature. We should have said that Whittington works without pay for the Communities in Schools of Greenwood Leflore, Inc. The JFP apologizes for the error.