Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Photo by Trip Burns.

Despite the pervasive notion that guns make people safer, science suggests otherwise.

"They actually pose a substantial threat to members of the household. People who keep guns in their homes appear to be at greater risk of homicide in the home than people who do not. Most of this risk is due to a substantially greater risk of homicide at the hands of a family member or intimate acquaintance. We did not find evidence of a protective effect of keeping a gun in the home, even in the small subgroup of cases that involved forced entry," a group of researches wrote in a 1993 article that ran in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The article challenged the conventional thinking at the time—which remains the conventional thinking today—and bolstered the long-held view in the medical community of treating guns as a public-health problem, and treating gun-induced trauma the same way doctors treat patients suffering from other traumatic events.

Consider, for example, that 30,000 people die every year in car accidents. The numbers were once higher but, over the years, stricter laws requiring passengers to wear seat belts and prohibiting the use of alcohol while operating motor vehicles have caused the number of car crashes to plummet.

Recognizing the public-health benefits of ensuring that people drive as safely as possible drove down the rate of vehicle deaths from around 26 per 100,000 people in the late 1960s to 10 per 100,000 today.

After the December shooting in Newtown, Conn., in which 20 children and six adults were murdered, public-health officials urged President Obama to intervene.

"The tragedy of gun violence is compounded by the fact that the usual methods for addressing a public health and safety threat of this magnitude—collection of basic data, scientific inquiry, policy formation, policy analysis and rigorous evaluation—are, because of politically-motivated constraints, extremely difficult in the area of firearm research," the group wrote in the Jan. 10 letter.

Pro-gun groups such as the NRA have resisted government-funded research about the effects of gun violence, however. An investigation by NBC News revealed that U.S. Rep. Jay Dickey, R-Ark., led a push in the mid-1990s to slash $2.6 million from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ultimately, center's budget remained intact but gun-friendly lawmakers succeeded in adding language to the CDC's appropriation bill in Congress that "none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control."

Meanwhile, the number of gun-related deaths tends to mirror deaths that result from other forms of trauma. In 2009, the United States saw 31,347 firearms deaths.

Of those, about 60 percent were suicides, and 37 percent were homicides. Homicide is the leading cause of death for young people ages 10 to 24, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. John Porter is a trauma surgeon in the emergency department of the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, and is on the frontlines of the public-health crisis rising from the cycle of gun violence.

"When a person gets traumatized, whether it's a gunshot wound or a car crash, what the doctor does at that point is not the end," Porter said. "There's a big path to recovery that includes nursing, rehabilitation, physical therapy, occupational therapy and also of the families that are involved because it's such a huge event."

Annually, medical costs and lost productivity from gun violence totals more than $70 billion, according to a 2007 American Journal of Preventive Medicine article, "Medical Costs and Productivity Losses Due to Interpersonal and Self-Directed Violence in the United States."

At UMMC, the path to healing begins in the ER, where a team of surgeons, residents and nurses stabilize the victim before there, the patient receives case managers, social workers, physical therapists and speech therapists who work not only to get the victim and his or her family on the road to recovery. A unique feature of UMMC's trauma program involves working closely with churches in the victim's community and talking to children, Porter said.

"Sometimes on TV, it makes it looks like you're a hero to be shot, but we want to point out all the pain and all the recovery involved," Porter said.

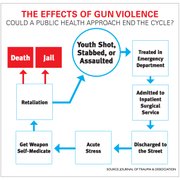

About 18 percent of patients seen in the UMC trauma center are penetrating trauma victims—shootings and stabbings—and Porter sees many of the same patients over and over. In fact, the trauma recidivism rate is around 30 percent, and the severity of the wounds worsens with each shooting, Porter said.

To Porter, treating gun-related trauma from a public-health perspective is similar to fighting an infectious disease pandemic.

"You have the host--that's the person who was shot. You also have the environment, which is where the person lives. And then the pathogen is actually the guns itself," Porter explained. Porter eschews debates about gun control, preferring instead to offer his trauma patients with information on how to store guns and ammunition more safely.

"I'm not in the business of saying who can have a gun, I'd just like the guns to be safer so fewer people get shot," Porter said.