Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Zero-tolerance and get-tough policies means once a child has been suspended, even the most minor offense can put him or her back into the system. Photo by Courtesy "Handcuffs on Success"

If it's not your kid involved, it could be easy to look the other way when zero-tolerance policies incarcerate children for minor offenses. But the effects of those policies are far-reaching: They undermine every step forward Mississippi schools try to make, and they cost every taxpayer in the state in terms of economic development.

Those are some of the conclusions of a new report, "Handcuffs on Success: The Extreme School Discipline Crisis in Mississippi Public Schools," issued jointly by the ACLU of Mississippi, the Mississippi State Conference NAACP and the Mississippi Coalition for the Prevention of Schoolhouse to Jailhouse Advancement Project.

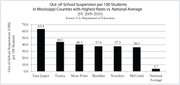

The stories of how Mississippi schools put kids on the path from classrooms to jail cells have resulted in numerous federal civil-rights lawsuits, most recently in Meridian and Lauderdale County. In the Jackson Public Schools, 96 percent of arrests made on school grounds during the 2010-2011 year were for minor offenses. Kids are sent to youth detention facilities for "normal adolescent behavior": talking back, wearing the clothes that don't appear on the school's dress code, being a distraction in the classroom--or the catch-all charge: "insubordination."

Zero-tolerance and get-tough policies means once a child has been suspended, even the most minor offense can put him or her back into the system. A youth-court judge in Meridian County put an 8th-grader on probation for fighting. Since then, the young man has been in an out of the juvenile justice system 30 times for infractions that include being a few minutes late for class and wearing the wrong color socks.

The report tells of extreme bias against African American students. Even in districts where the majority of kids are white, far more black children are treated harshly from their first offense. For every one white child suspended during the 2009-2010 school year, more than three black students received suspensions.

"The white kids don't get handcuffed. If a white kid gets into an altercation it depends on who they are and how they act," a Jones County 9th grader told investigators. "... They won't go to jail. They will just get suspended for three to five days and come back to school. ... I was handcuffed and arrested for getting into a fight at school. They took us straight from school to the detention center where we were stripped of our clothes, forced to shower in front of others, and required to take a drug test. We had to spend the night there. I had never been in trouble in school before."

Taxpayers are paying the price for harsh treatment of young people in Mississippi.

"These extreme policies have serious consequences ... for the entire state educational system, as they effectively act like a giant brake on statewide school-improvement efforts," the report states. "There are no successful schools that suspend, expel and refer large numbers of students to law enforcement."

To improve student achievement, schools have to maximize the time students engage in academic pursuits; however, suspensions and arrests result in lost learning time and in students being increasingly alienated toward school. As students become more removed from academic success, teachers are less effective, relying more on remedial instruction and harsh discipline. It's an unproductive cycle.

The presence of armed guards adds to the escalating negativity of the environment. "The look and feel of many schools changes dramatically with the addition of security, becoming less welcoming and more threatening to students," the report states. More threatening environments lead to increased hostility. "Young people resent being treated as threats; they lose faith in the goodwill of police when they believe they are being treated unfairly; and they frequently become antagonistic toward law enforcement in response."

Harsh, unwarranted discipline of children results in huge costs for Mississippi taxpayers. Funding for prisons has increased 166 percent from 1990 to 2007, while funding for public schools continues to decline year after year. "Thus, in fiscal terms, the State is prioritizing incarceration over education," the report states.

Costs of guards, security equipment, court costs and the cost of running alternative schools is just the tip of the financial iceberg to Mississippi. The long-term cost of kids dropping out of school--often the result of harsh disciplinary practices--is far greater. From lost tax revenue to higher public-health, public-assistance and criminal-justice costs, the cost "is likely tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars every year," the report states.

"Economists have estimated that each student who graduates from high school, on average, generates economic benefits to the public sector of $209,100 over her or his lifetime. Thus, the more than 16,000 members of every Mississippi 9th-grade class who fail to graduate on time cost the state (more than) $3 billion."

Beyond laying out the scope of the problem, the report also offers several recommendations to alleviate the problem. From developing a graduated approach to discipline to improving accountability and developing training curricula, the report provides steps based on best practices in other districts nationwide. The Baltimore City school district, for example, has lowered its suspension rates by a third and increased graduation rates from 60.1 percent in the 2006-2007 school year (prior to discipline reform efforts) to 71.9 percent in the 2010-2011 school year--an 11.8 percent increase

"There is no great mystery to creating safe and effective schools," the report concludes. "Young people need to feel valued and cared for; they need to be provided the appropriate resources; and they need to be allowed to make the same mistakes that all of us make when we are young."

Comment at www.jfp.ms. Email Ronni Mott at [email protected].