Wednesday, November 13, 2013

The prospects of the project to develop a legitimate entertainment district have wilted as the legal and political posturing has heated up on Farish Street. Photo by Trip Burns

Socrates Garrett sat silently in the second-story conference room of the Mississippi secretary of state's North Street offices on Oct. 29, his legs crossed and his eyes fixed on his former business partner, lawyer and developer David Watkins.

Watkins was there to deny allegations of securities fraud for misusing money from Garrett's company, Retro Metro LLC, when Watkins was the managing partner.

When the hearing adjourned, the men exited the building without saying a word to each other. The high-profile developer and contractor aren't talking these days, and what was once a budding business relationship between two of Jackson's biggest fish, built to rescue some of Jackson's more challenging projects, has devolved into a very public and messy battle.

In recent years, Watkins has taken credit for several successful renovation projects—the King Edward Hotel, the Standard Life Building and Retro Metro, which renovated a large chunk of Metrocenter Mall.

Watkins has other big ideas on the horizon with plans documented on a website that features a slide show which, if made into reality, would transform the capital city into a social and entertainment Mecca in Mississippi, including Town Creek waterfront development, a Mississippi arts district downtown and even a marina near the proposed, but still unrealized, downtown lake.

Urban development is a second career for Watkins, one he took on after 35-plus years of practicing law. He had made enough money as a lawyer to retire comfortably.

But now, the grandfather of four is waging the fight of his professional life—a three-front legal battle that could end his career, tarnish his legacy and indefinitely delay one of Jackson's most coveted development projects.

A Legal Morass

That Watkins is involved in all of these legal battles is no surprise—he has been a thread in much of Jackson's recent development scene, where legal disputes between contractors and developers are not uncommon.

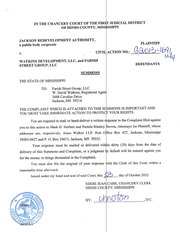

That is certainly the case with the Farish Street Entertainment District, where two contractors have placed liens on the property against Watkins Development for unpaid work, and Watkins Development has placed liens on the same property against the Jackson Redevelopment Authority.

This is the first front on which Watkins is fighting for control and his image.

Watkins got involved with Farish Street in 2009. He was a hot commodity when he agreed to help with the project, as he says that some city officials begged him to do. The King Edward Hotel was freshly re-opened after 40 years as an eyesore, and the Standard Life building was looking grand again, transformed from an aging office tower into an apartment building for the young professional set, as well as corporate housing, with him getting much of the public credit. The Belk building at Metrocenter Mall, which sat vacant and was quickly deteriorating, housed part of the Jackson Police Department and had new life—at least in part due to Watkins and his partners in his various firms.

But Farish Street is a different kind of development. It's not a building; it's a district. Businesses already exist on the street, but the infrastructure was deeply challenged from years of neglect. The area, once a booming economic hub for the Jackson's black community, had been a proverbial wasteland for decades. 'Unknown and Untested'

In 2009, Watkins took on $1.5 million in debt from the former leaseholder Performa, the company that had finished Beale Street in Memphis, and the Mississippi Development Authority kicked in a $5.4 million low-interest loan. He started a new firm, Farish Street Group, and brought in local contractor Socrates Garrett, attorney Robert Gibbs, businessman Leroy Walker, physician and professor Dr. Claude Brunson and former New Orleans Saint Deuce McAllister as partners.

Jackson architectural firm Dale Partners Architects developed the master plan for the entertainment district complex, which it described on its website as "five connected buildings in the Farish Street Historic District. These five buildings will support seven restaurants featuring four premier chefs paired with equally talented musicians from Jackson." The restaurants would have a centralized kitchen, the site said.

After he took over the project from Performa, Watkins put the MDA money into the infrastructure of the street and sewer system. He began to renovate the buildings and negotiate leases with potential tenants. He courted businesses such as B.B. King's Restaurant & Blues Club, a small chain with locations in Memphis, Nashville, Orlando, and Las Vegas that pledged to open an anchor venue on Farish in the block between Amite and Griffith streets.

In June 2011, Watkins kicked in $4.67 million of his personal money to the project. Watkins and the Farish Street Group then asked JRA for an $8 million bond in November 2011. In March 2012, JRA entered a memorandum of understanding that it would secure a loan for $10.25 million, to be paid back with proceeds from the entertainment district. But the JRA board never issued the bonds, saying in a lawsuit filed in late October 2013 against Watkins Development that FSG had failed to meet deadlines, constituting a default on the contract.

Build-out delays occurred, Watkins says, because financing was hard to find during the Great Recession and the project was "high risk" because Jackson is an "unknown and untested" market. The project suffered a crushing blow in June 2012, when a second engineering evaluation, requested by Dale Partners, found that the structure set to house B.B. Kings had no foundation beneath it. A structural engineer had earlier given the building a "good report," Watkins' attorney Lance Stevens told the JFP.

The foundation discovery added about $1.5 million to the total cost of the project, and forced Watkins to shuffle more resources into the first phase of the project.

Liens and Acrimony

Two contractors—Ellis Custom Construction and Dale Partners Architects, P.A.—filed liens against Watkins for non-payment for completed work on properties on Farish Street in February 2013.

The situation quickly deteriorated into a war of words, with Watkins claiming JRA was responsible, and JRA claiming Farish Street Group was at fault.

FSG minor partner Leroy Walker told the Mississippi Business Journal that the JRA's decision to remove Watkins from the project was understandable. "I think that David is a credible individual," Walker told the MBJ's Ted Carter, but "I do think some mistakes were made... . I think his effort was outstanding, but not the results."

The JRA board asked Watkins for an update in April, prompting Watkins to draft an 834-page document outlining the work that Farish Street Group had completed to date, as well as the current standing and future outlook of the project.

Watkins appeared at the April 2013 JRA board meeting to present the update, but board member Beau Whittington had to leave, and the meeting abruptly ended when the board lost its quorum before Watkins could present. He refused to provide the "proprietary" document to the JFP.

With public scrutiny mounting and lawsuits moving forward, Watkins said he had a plan to sell the development project to a third party. Watkins would take a back seat to a new unnamed developer, who would take advantage of the contracts and leases Watkins had already negotiated, and use historic tax credits Watkins Development had accrued. Watkins says these tax credits, earned by investing in the buildout, would not be available if the remaining work is not done by or in conjunction with, FSG.

But the JRA Board abruptly canceled the master lease Watkins had held since 2009 on Sept. 25, 2013, Watkins and his lawyer Lance Stevens to write a 10-page letter to JRA Chairman Ronnie Crudup. In that letter, Watkins, through Stevens, detailed what they saw as JRA's lack of support and explained the setbacks they had encountered in renovating a historic district.

"In spite of the JRA and its agents and attorneys having actual knowledge of negotiations underway to sell the development project to third parties ... the JRA did not give Watkins or his partners notice of the termination before taking action or a reasonable opportunity to come before the board before taking such devastating action," Stevens wrote to Crudup Oct. 9.

"The details and history of this development plan are many and complex. However, the underlying and undeniable truth is that the JRA has been given inaccurate information and bad advice and has acted on that information and advice resulting in substantial violations of the personal, property and civil rights of Watkins and others."

JRA maintains that it did not secure the $10.25 million in bonds because "(Farish Street Group) failed to satisfy the requirements and consequently, no funds were ever provided by JRA to FSG." The JRA board, through spokesman Crudup, has since refused to talk about FSG or Watkins, citing the ongoing litigation.

"It's very frustrating that after 14 years, we haven't seen the area developed," State Sen. John Horhn, who sponsored the legislation that authorized the $5.4 million MDA loan, said in late October. "There are other financial contributors and developers interested, but the current parties are so angry at each other that they can't see beyond playing a game of 'gotcha,' and yet the project is going wanting all this while."

The Power of JRA

JRA itself is embroiled in controversy, and not just involving Watkins.

Tired of hearing about Farish Street delays, Ward 3 Councilwoman LaRita Cooper-Stokes placed on the Oct. 14 city council agenda a request to "unauthorize" the Jackson Redevelopment Authority.

Council clerk Beatrice Byrd read the motion and, after some brief confusion, Ward 1 Councilman Quentin Whitwell, Cooper-Stokes' polar political opposite, moved to adopt the motion. Council waited for another member to second, so it could be put to a vote.

And then, silence. All eyes were on her, but Cooper-Stokes wouldn't second her own motion, so it couldn't be considered for a vote. It died, that day, for lack of a second. Council President Charles Tillman placed it in the planning committee.

The scene was indicative of Jackson's approach to dealing with the bureaucratic entity, which was formed in 1970 and originally designed to develop and manage downtown parking garages.

The majority of Jacksonians can't tell you what JRA does, let alone name a member of its board, but these members manage more than $40 million in public assets. The terms of the board members are five years, but two, Ronnie Crudup and financial adviser Brian Fenelon, are now serving beyond their terms by more than a year, and a third, businessman Gregory Green, was nearly four full years out of term when Mayor Chokwe Lumumba replaced him last month with loan originator Michael Starks Sr.

The task to appoint these members falls to Lumumba, pending approval from the Jackson City Council. Crudup, the New Horizon pastor who calls the shots as board chairman, has been out of term since Aug. 13, 2011. Former Jackson Mayor Frank Melton appointed him, along with Fenelon and former state legislator John Reeves, whose terms technically ended on Aug. 13 of 2012 and 2013, respectively.

It's unclear whether a changing of the guard will change the way the board operates, but Lumumba said he thinks it will.

"Any time you have open positions and you can get your own people in there, that is going to make a difference," Lumumba said. As of Nov. 12, Crudup, Fenelon and Reeves still held their positions.

The seven-member board has power, under current state law, to establish and construct municipal parking facilities for motor vehicles belonging to members of the general public, and to rent, lease, purchase or acquire land and property for public purposes—the historic Farish Street district or the land on which the convention center now sits, for example.

It also has the power and authority, under state law, "to rent, sell, convey, transfer, let or lease such facility and related structures or any portion thereof, or any space therein, and to authorize commercial enterprise activities other than the parking of motor vehicles on leased property comprising any part of such parking facilities and related structures," which is what it is doing with Farish Street and, as another example, the land on which the refurbished and about-to-open Iron Horse Grill sits.

As with many laws passed when gas was less than 50 cents a gallon, the interpretation of JRA's charter has changed significantly over the years and without a single change in the language of the law.

JRA proponents will tell you the board has done some great things for Jackson. It systematically bought all the land on which the convention center now sits. It also bought the land on which a proposed convention center hotel will perhaps, one day, stand.

But even JRA's arguably biggest achievement, the convention center, comes with a caveat: the ongoing hotel dispute. During the Melton administration and under that mayor's orders, the board sold the land for the proposed site to Houston development company TCI, which unveiled impressive plans to build a hotel complex—that withered on the vine, leaving the city without access to the land until recently.

After Melton died and Harvey Johnson Jr. was returned to office, it took Johnson two years to get the land back and re-open the bidding process to build a hotel across Pascagoula Street from the convention center. After two requests for proposals and two submitted proposals, the city still does not have a developer for a hotel as of press time.

JRA also bought most of the land and buildings on Farish Street, and has contracted two different developers in the last 15 years trying to put businesses in those buildings.

Then There's the Secrecy

While most public entities have mechanisms in place to ensure public access to information, JRA operates, in many ways, like a private entity, although the city of Jackson and, thus, taxpayers provide its funding.

The monthly meetings on the third Wednesday of every month may be open to the public, but that notion is, to put it plainly, a farce.

Take the Oct. 22 meeting at the Richard J. Porter Building across from City Hall. At that meeting, the board took up three issues. The first was an ongoing discussion about Union Station, which had been experiencing break-ins and recently had the roof replaced (with insurance money, although JRA did pay the $5,000 deductible). The second was a change in plans on a property JRA had sold Jackson State University for the purpose of building a mixed-use building on the outskirts of campus.

The third item was titled "Consideration of and, if appropriate, actions with respect to Authority's termination of its lease with Farish Street Group LLC, litigation filed by Dale Partners Architects, P.A., against the Authority, Farish Street Group, LLC, and Central Mississippi Planning and Development District and lien notice filed by Watkins Development, LLC."

By lumping all those issues in the third agenda item together, the board used a legal excuse to go into executive session without publicly discussing the letter Watkins sent.

The JRA board did the same thing to discuss Farish Street and proposals for the convention center hotel at the Aug. 21 meeting, 28 days before they cancelled the Farish Street Group's contract.

Other public bodies, such as the Jackson City Council, discuss ongoing projects at length in public, right up until the point they need to receive an update on an ongoing legal dispute—which honors the spirit of open government.

Stevens also complains that JRA did not invite Watkins to a meeting to give an update on the project prior to the lease termination, nor did they, according to the Watkins camp, elect to call him to offer any notice that the contract was up for cancellation.

The Fraud Question

The second front in Watkins' battle is a fight to maintain his reputation, his career and his legacy. The challenge he faces here is an allegation of securities fraud.

Mississippi Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann, though his attorneys, is accusing Watkins and his company, Watkins Development, of committing securities fraud when he allegedly misused half a million in tax dollars awarded for the Metrocenter Mall redevelopment in Jackson to purchase a building in Meridian for a different project.

Secretary of state attorneys issued a "notice of intent" July 30 to impose administrative penalties and demand restitution from Watkins for the money transfer.

In conjunction with the order, the secretary of state held an administrative hearing that began Oct. 29 and concluded the next day to allow Watkins to address the allegations that he redirected part of a $5.2 million bond to help fund his Meridian Law Enforcement Center project.

Mississippi Business Finance Corp. awarded the bond April 12, 2011, for the revitalization of the first floor of the old Belk building in Metrocenter.

Watkins doesn't deny that he transferred $587,084.34 on June 8, 2011, from a BankPlus account registered to Retro Metro to a real-estate closing account in Meridian. He is arguing he was within his rights to do so.

As the hearing wrapped up, Watkins denied any wrong-doing and finished his testimony by answering his attorney Brad Pigott's query: Did he have any reason to conceal information from investors, as the state has suggested?

"Mr. Pigott, I have every reason to avoid any kind of concealment or any fraud," said Watkins, who, that same month, took over as the new chairman of Downtown Jackson Partners. "I've spent almost 40 years as a lawyer, and over half of those years in public finance and public bonding. Securities fraud is a career-ending disaster."

Watkins added that his "whole life has been one of integrity" and commitment to community and good works. "I would never do anything that would put myself in a position that would end my career or damage my reputation or the reputation of the good works I've been able to accomplish. This is a serious problem for me, personally. It's caused a lot of emotional distress, because it's undeserved," he said.

The secretary of state also accuses Watkins of failing to disclose in the bond documents "the intent to use and or convert any portion of the proceeds to finance the activities of MLEC." Because he did not disclose that intent, it could be "material omission" under the "General Fraud" section of the Mississippi Code of 1972.

Watkins' lawyers claim that the investigation is just an extension of the attack on Watkins by his foes—the JRA, its lawyers, and his former business partner, Socrates Garrett.

Garrett, who owns Garrett Enterprises and the Mississippi Link newspaper and is a former partner in both Retro Metro and a current partner in the Farish Street Group, has been at loggerheads with Watkins ever since Watkins sold his portion of Retro Metro late in 2011.

At least publicly, Garrett has been mum on the apparent feud. But under his leadership, Retro Metro also filed suit against Watkins Development for the money transfer the secretary of state is investigating.

Garrett did not respond to messages left at his office for comment for this story. His contracting company, Garrett Enterprises Consolidated Inc., is responsible for building several notable projects in the city, including the One University Place shopping center at Jackson State University. In 2010, his company completed New Horizon Church International, a new $2.5 million site for JRA Chairman Crudup's church.

Tangled Legal Web

The other player in this story is the New Orleans-based law firm Jones Walker. It has avoided headlines to this point, but its lawyers are undeniably entangled in the Watkins controversy.

Jones Walker attorney Zach Taylor represents the JRA board in both litigation and bond proposals, and Jones Walker collects payouts as it serves as bond counsel for JRA on most of Jackson's development projects, most recently, the Iron Horse Grill under construction on Pearl Street.

Additionally, Jones Walker represents Retro Metro, and by extension Garrett and businessman Leroy Walker, another former Watkins partner, in two pieces of litigation against Watkins Development.

In March, Taylor filed for a waiver for conflict of interest so Jones Walker could represent a tech company that wished to lease space on Farish Street, and that would have placed a non-entertainment business in the entertainment district.

It was a Jones Walker attorney, Keith Parsons, who said, under oath on Oct. 29 that he filed the allegations against Watkins with the secretary of state's office.

U.S. News and World Report ranks Jones Walker as a tier-one firm, and both Taylor and Parsons are named among the nation's top attorneys in their field by the same publication.

"Jones Walker is the common thread for all of David Watkins' current problems," Sam Begley, a Jackson attorney and Watkins' former partner in Retro Metro, told the Jackson Free Press.

After JRA filed suit against Watkins Development in an attempt to recover the money Watkins had put into Farish Street, Stevens filed a motion Oct. 30 to disqualify Jones Walker from representing the board. In his motion, he charged that the firm was helping clients "attempting to steal the Farish Street project from (Watkins)" with its involvement with various lawsuits spinning around the beleaguered developer and his various projects.

Stevens argued that the tangled relationships between attorneys and principals involved in the various lawsuits create a situation that is "ripe for corruption and present an unacceptable ethical scenario."

In an interview, Stevens said: "David Watkins does not get a warm and fuzzy feeling when he hears the words 'Jones Walker.' I think the feeling is mutual."

When reached by phone, Jones Walker's JRA attorney Zach Taylor said he doesn't comment on ongoing litigation. "I know some attorneys think it's a good idea to play out cases in the media," he said, "I'm old school, and I am not one of those lawyers."

Parsons did not return phone calls for comment on this story.

'Delay or Doom'

While the litigation and acrimony play out, Farish Street sits unfinished. Completing the project was on the tip of every political candidate's tongue during the 2013 municipal elections, and getting a new developer for the project was a common theme.

Not much has changed in the past two years. Some of the facades on the buildings have been cleaned up, and the bricked streets with fancy light fixtures look nice. But the buildings are empty, many of the windows are busted out, and some buildings have what looks like kudzu growing through their floors.

In one of the abandoned warehouse spaces at 272 Farish St., in the first block between Amite and Griffith streets, the only signs of life are a makeshift pallet where a person has been sleeping and a pile of trash where someone had Krystal burgers for supper the night before.

Where the project goes from here is anyone's guess, but Watkins, in his 10-page letter to JRA, presented two scenarios through lawyer Lance Stevens.

The first: The JRA board stands by its decision to boot Farish Street Group from the project, and the litigation stands.

If that happens, Stevens warned Crudup that "the inevitability of protracted litigation in federal court could delay or doom the project" if Watkins does not continue to be involved at some level.

The second: JRA reverses its decision and brings Watkins back into the fold to sell the project to a third party, perhaps a new developer who can breathe in new life and finish the project.

Crudup said in an interview with the JFP in late October that JRA "made a decision as a board with what we think is the best interests of the city."

"That was our determination," Crudup added. "I'm aware of a lot of what is being said (such as in Lance Stevens' letter), but it's not productive for us to debate that in the press."

Both JRA Chairman Ronnie Crudup and Lumumba seem open to the idea of bringing back the other members of Farish Street Group, including Garrett and Walker.

"We're open to anyone who wants to come to the table and prove that they can do a deal that will help in developing the district," Crudup said.

"If some of those folks happen to be people who were involved in the previous deal, and they can prove to us that they have the capacity to finish the project, then we would consider them like anyone else."

What's Next for Farish?

Rumors surfaced last week that behind-the-scenes negotiations had begun in an attempt to protect the interests of all the parties involved, but neither side would confirm or deny that talks were under way.

The Central Mississippi Planning and Development District, the entity who represents the MDA's interests, sent a letter to JRA interim Executive Director Willie Mott on Nov. 12 urging the board to withdraw its motion to cancel the lease.

In that letter, the CMPDD said JRA did not give it proper notice under the terms of the loan, and asked it reinstate Farish Street Group, and submit notice of its intentions, before going forward with the termination.

Despite the acrimony, Stevens, speaking on behalf of Watkins, said there is still ample room for discussion between the parties to resolve the issue and get the project completed in a timely manner. "We have offered that olive branch," he said.

Sen. Horhn said he can foresee an agreement where Watkins is involved, but not in a leadership position.

"I think what needs to be developed is an exit strategy for Mr. Watkins from the Farish Street development, but one that compensates him fairly for the work that he's done," he said. "We're at a point where a new developer can come in with a fresh equity to get the thing done."

"I think that if cooler heads will prevail, and JRA and Mr. Watkins sit down and try to work their way through this process, we can get some development on Farish Street, and very soon."

This is part 1 in an occasional series on "The Battle Over Downtown." Have more information on this saga or others affecting downtown Jackson? Email City Reporter Tyler Cleveland at [email protected] or call him at 601-362-6121 ext. 22.

The players:

David Watkins was once considered the Golden Boy of Jackson after he successfully led redevelopment of the King Edward Hotel and Standard Life Building. He is the owner of Watkins Development and founded Farish Street Group and Retro Metro, LLC.

Socrates Garrett is Watkins' former partner in Retro Metro and still a member of Farish Street Group. A contractor, he owns Garrett Enterprises and the Mississippi Link newspaper.

Lance Stevens & Brad Pigott are Watkins' attorneys. Stevens is representing Watkins in the ongoing dispute on Farish Street, and Pigott, a former U.S. attorney, is defending Watkins in his proceedings related to the Mississippi secretary of state's investigation.

Zach Taylor & Keith Parsons are both lawyers with the Jones Walker law firm. Taylor represents the JRA board, and Parsons testified against Watkins during the secretary of state hearings.

The companies:

Watkins Development LLC is David Watkins' main business entity. It's a company with around a dozen employees and more than 50 projects on its radar.

Farish Street Group LLC is a firm Watkins founded with initial investment from Watkins, Garrett, attorney Robert Gibbs, Dr. Claude Brunson, developer LeRoy Walker and football star Deuce McAllister to redevelop the Farish Street Entertainment District.

Retro Metro LLC is a company Watkins founded with Garrett, Walker, and several other small investors to renovate parts of Metrocenter Mall, mainly the abandoned Belk building.

One of the major complaints in David Watkins' attorney Lance Stevens letter to the JRA board is that neither the city, nor JRA, has invested in the Farish Street project. See page 17 for a list of investors in the project.

Initial Investors in Farish

Watkins Development, LLC $250,000

Robert Gibbs $50,000

Claude Brunson $50,000

Deuce McAllister $50,000

Socrates Garrett $50,000

LeRoy Walker $50,000

MDA/CMPDD loan $1 million

Subsequent Investment

Watkins & third parties $6.6 million

MDA loans to FSG $4.4 million

Total $12.5 million