Wednesday, September 4, 2013

On a recent trip to the William F. Winter Archives and History Building, a couple of enterprising reporters dug up some old pictures and articles about Capitol Street. A picture dated Jan. 20, 1967, taken from the West Street intersection looking east, shows a bustling business district with independent businesses lining the street.

There are people in the picture. There are cars in gridlock (without road construction). There is life.

As the caption on the now-tattered newspaper clip said, the picture "reveals a busy downtown artery with all the hustle and bustle of modern city life."

A lot has happened since 1967, the year some of the conspirators who murdered three civil-rights workers in Neshoba County were convicted, and hardly any of it has been kind to Jackson's retail scene.

Looking at the same street from the same view today paints a picture of what was, what is and what could be.

Jackson's downtown retail is either flat, or moderately improving, depending on whom you talk to, but it's not anywhere near the level of occupancy it once enjoyed.

Between 1970 and 1980, the west end of Capitol Street, a microcosm of the entire downtown scene, devolved. An article in The Capital Reporter by writer Richard Hart, dated Sept. 24, 1981, describes it best: "The trains slowed to a halt, the hotel closed up, and the few last diehard merchants hung on for dear life."

That article, titled "Saving What's Left of Capitol Street," reads like it could have been written yesterday, with lines like "The Farish Street renovation just blocks away has not spread interest into that part of town."

Those merchants are even fewer in number now. Lott Furniture, The Mayflower Cafe and a handful of other businesses have hung on long enough to see the King Edward Hotel renovated and reopened. Jackson-based BlackWhite Real Estate Development is working on renovating and reopening some mixed-use space across the street from the hotel, but it's still in the early stages.

Even with great excitement and myriad promises of a revitalized downtown over the last decade, one major question still looms: Where is the corner store?

The Flight of Retail

Stacy Mitchell, a Portland, Ore.-based senior researcher at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, said the decline is not exclusive to Jackson or southern cities.

"This has been a phenomenon that has been experienced across the country," Mitchell said. "It began in the 1950s and '60s as shopping malls started popping up on the outskirts of towns. By the late '80s and '90s, big-box stores started popping up. That really dealt a severe blow to a lot of downtown retail areas. As one business left, it made all the other stores suddenly a little less convenient than they were before, because you couldn't fill all your needs in one area anymore."

In Jackson and many other cities, the problem was ironically exacerbated by the end of Jim Crow laws: Black business districts such as Farish Street and Beale Street lost the bulk of their customers to shopping areas they were previously restricted from, and suburban malls grew to meet the demand of white families fleeing newly integrated public schools and, thus, the city. "Urban renewal" didn't help, meaning that rows of previously successful local businesses downtown were razed for office buildings and parking lots.

Mitchell says savvy cities started doing something about the shrinking retail problem in the early 1990s, when they realized the migration of business was not healthy for the downtown economy. They reinvested in downtown and stopped putting all their infrastructure dollars into the far-reaching corners, chasing real-estate demand.

Meanwhile, Jackson was sluggish to respond to downtown's needs, and instead, began to expand its borders to keep the people who were moving outward inside the incorporated city limits, but far from downtown.

The businesses on Capitol Street continued, and still continue, to scrape by, surviving on the promise that the area will eventually return to its former glory. And so it goes in most pockets of downtown, where the streets turn into a ghost town at 5 p.m.

At the eastern end of the strip, Jackson's landmark restaurant Hal & Mal's has survived on Commerce Street, a block off State Street, since 1982. Owner Malcolm White confirmed that the downtown described in the 1981 article was very real.

"There was no life downtown after the sun went down," White said. "It was 'move 'em in, move 'em out' when it came to people working down here. When people came to our restaurant, they were coming to downtown with the intention of coming here and nowhere else."

That has changed in recent years. Downtown nightlife lives beyond Hal & Mal's, with bars like Underground 119, Martin's, Fenian's, Ole Tavern on George Street, F. Jones Corner and a few other watering holes dotting the landscape. There are restaurants like Wasabi, Steve's Uptown, Miller's Grill, Basil's, Mayflower Cafe, Adobo, Parlor Market and Elite Restaurant, but the list of businesses long gone is even longer.

"If you look at the big picture, the retail and business scene in downtown has gotten a lot better since the 1980s when we were first opening up," White said.

"It's just a slow, slow process."

'Utopian Planning'?

Getting independent businesses to open or relocate downtown is a tricky task, and the number of ideas for creating the environment for growth seems to far outnumber entrepreneurs capable of, or interested in, opening and sustaining a retail business there.

Jackson State associate professor of Urban and Regional Planning Mukesh Kumar has written about the problems that plague downtown's retail scene. He believes the city and its civic leaders must market downtown as a means to an alternative lifestyle for people who want to live in an urban setting. More people, he says, will create the demand for retail that the capital city needs.

"The biggest difference between living in a suburb and living in a downtown area is transportation—how you get from point A to point B," Kumar said. "If I still have to get into my car and drive to the grocery store or to the movie theater, then for what am I living downtown and paying higher rent?"

Kumar has a few ideas of his own, like re-striping all the streets to accommodate bike and walking lanes, just to start, but he'd rather see the city have a real conversation that is based on creating desire for commercial and residential space that isn't tied to some big multi-million dollar project.

He sees projects like the District at Eastover, the renovations of Farish Street and Capitol Street, the Westin Hotel and the Convention Center Hotel as positives, but doubts they will create the climate for growth that Jackson would like in downtown.

"Instead of thinking about project A, project B and project C, we need to be thinking about how these projects collectively will get us to where we want to be," Kumar said. "(Renovating Capitol Street) is probably going to create a little more demand for housing in and around this area, but it doesn't really fit with what we're trying to create."

Jackson architect and developer Roy Decker opened his architecture firm Duvall Decker with wife Anne Marie Decker in Fondren in 1998. He has since taken on significant projects in midtown and, more recently, in west Jackson, trying to replace the blight that has brought land value, all across the city, down for years.

Looking out the window of his State Street offices in the heart of Fondren, you can see thriving restaurants and retail hot spots, but it wasn't always like that. Twelve years ago, the Mississippi Department of Wildlife and Fisheries was the only entity on the block. Now, residents and visitors enjoy restaurants like Rooster's, Basil's, Sneaky Bean Coffee Shop, and several retail clothing stores.

Decker agrees with Kumar that large developments will not turn the fortunes of downtown Jackson around. "We don't need one big project here and another there," he said. "What downtown really needs is a coordinated, strategic plan that can build consensus among the city leaders."

The Philadelphia, Pa., transplant said another problem with the prospects of downtown is that there is a lot of talk, but too little action among aspiring developers.

"Utopian planning is rampant," Decker said. "It's not just in downtown, it's the entire architecture and development market. We have these new urbanists proposing visions of an endgame, but there's no connectivity among the projects, and they end up creating buzz, but produce no results."

That said, Decker, who is in the process of contracting on housing developments in downtown that he's not ready to go public with, is optimistic about the market there.

"You're going to see the same thing that happened in Fondren happen (downtown)," he said. "It's just a matter of providing housing for a diverse crowd that reflects Jackson. You want people of mixed income living in the area so you don't create a yuppie paradise that only the well-off can afford to survive."

North Toward Fondren

Kumar uses Fondren, the area around Decker's Jackson office, as an example of what could be in the downtown area, if only there was affordable housing.

"It's a natural progression for the art community to move where you can live relatively cheaply but you aren't in the suburbs," Kumar said. "That's why Fondren and Belhaven are doing so well. The boutiques and niche stores move into the area to cater to that clientele."

One example of what Kumar is referring to is the renaissance that is currently happening in midtown. The once-blighted community is back on its feet, attracting businesses and fostering an artistic sense of community.

Decker provided the first bit of affordable housing by building a series of innovative affordable houses. Then Midtown Partners and the Business Association of Midtown, known as BAM, have partnered with Millsaps College Else School of Business to provide support—from taking out the trash to providing financial instruction—to businesses that want to relocate to the area.

Whitney Grant, the creative economies coordinator for Midtown Partners, said another driving force behind the area's resurgence has been the strategic plan the various groups developed together, including BAM, Midtown Partners and the neighborhood association.

"I don't know where we'd be without our strategic plan," Grant said. "When we go into a meeting with a potential entrepreneur, we can point to a building on a map and show them how their investment in that building will affect all the buildings around it."

Malcolm White, now the state's director of tourism, says residential demand is there for downtown, but there just aren't enough affordable places for people to live. He points to waiting lists for apartments at the Standard Life Building on Pearl Street and the King Edward as a sign that more people will come if there is affordable housing.

Flats at the Standard Life, which has rentals ranging from $975 for a one-bedroom apartment to $2,025 for a two-bedroom, two-bath apartment, are anything but affordable for the average Jacksonian. Data from the 2010 census show Jackson's median household income to be $34,567.

"It costs so much to go in and renovate these residential areas that it's a slow process," White said. "But there are some mixed-use projects that are soon to get off the ground, and we'll see more affordable housing in the future."

Catering to the Day Crowd

The message from downtown's business improvement district is rosier, however.

Downtown Jackson Partners spokesman John Gomez maintains that local stores and boutiques that cater to the business community are doing well there.

"Any retail we get right now is going to be niche retail," Gomez said. "We've had some success with a few jewelry stores and office supply stores... stores that cater to that 8-to-5 business crowd."

Gomez points to Carter Jewelers, which has been in the same location on High Street, on the edge of downtown, for 160 years. Unlike a startup, Carter has a clientele that travel from all over the state to purchase a product.

"What I think has hurt the business downtown is the city has shackled us with some really high taxes," Carter's owner Jerry Lake said. "Taxes have to be passed on in the form of rent, and I don't know how some of these business are paying it. The city has been great to us over the years. We've worked with different mayors and the police protection we've been provided has been wonderful; our only complaint is the taxes."

Lake paid $14,928 in taxes in 2012 at 711 High St., which has an appraised value of $486,120 and an assessed value of $72,918, according to public tax records.

Gomez said DJP is banking on downtown's eateries and entertainment spots to help bring people back downtown after dark. Retail, he said, is more about daylight hours.

"Our numbers just don't mesh with what we're looking at," Gomez said. "We're trying to grow our culture and restaurants and bars to give people a reason to come back after 5 p.m. That's where we are focused right now. We are also trying to convince someone to open up a small corner grocery, so we can support that residential growth."

Some residents downtown say that, despite high residential occupancy rates, downtown can feel like a ghost town at night—perhaps due to many apartments owned or rented by absent or corporate tenants. Few residents, few customers for local drugstores, restaurants and gift shops at night.

Gomez said the belief that downtown has a good deal of taken-but-unused housing isn't "necessarily true." He says entrepreneurs don't want to take the risk.

DJP, he said, is focused on one-on-one contact, looking for a local entrepreneur willing to take a chance and work out a deal with local government to get some tax relief for the first few years of operation. That way, he said, they will have time to figure out what they need to carry to get support from the local community before they hit a financial crunch and have to close.

One business that went that route was the Standard Life Bodega, which opened in November 2010, and closed in April 2012.

"It's tough when you are a local retailer, and you don't have the buying power of a national company," Gomez said. "We are just going to have to keep trying until we get a business that the local residents can support."

That is, don't hope to wander into local quirky shops after happy hour soon like you can in Austin, Texas, or Athens, Ga. That's not the focus, at least of Gomez' group.

'None of This Is Easy'

Other cities have successfully turned their downtown areas around, and Jackson could be the next one to follow suit—with the right focus, organization and local will.

Mitchell said Jackson would probably benefit from a group she has worked closely with, the National Main Street Center, a non-profit based out of Washington, D.C., that has helped more than 2,000 communities reclaim their downtown area, creating $54 billion in investments and 450,000 jobs, according to the group.

"It's a subsidiary of the National Trust for Historic Preservation," Mitchell said. "It's worked in thousands of communities and has quite a successful track record. The way it works is a local organization gets created as a chapter of the Main Street Center, then organizers come in and work with the citizens in the community and civic leaders to come up with a decent formula for what to work on."

Mitchell said another step cities can take, and Jackson apparently is in the process of doing, is to improve the quality of the streets and the infrastructure underneath them. On top of the $10 million makeover to Capitol Street, Mayor Chokwe Lumumba proposed a budget last week that will pump an extra $22 million into public works, bringing the city's total expenses on public works to a whopping $398 million for the coming year.

"None of this is easy," Mitchell said.

"There is a lot of evidence now, through consumer surveys and things like that, that show there is a growing interest in independent business and in walking and riding bikes for transportation. When I got in this business, those things were in a downward spiral. Cities can capitalize on these larger trends, they just have to have community and civic leaders who are dedicated to making it work."

Jackson thought it had that in 1981. The potential was there, and still is. White puts it best:

"I used to tell my brother Hal all the time that we would see the revitalization of downtown in our lifetimes," he said. "It's happening, it's just extremely slow. I still believe it will get there. I just begin to question whether I will be alive to see it."

Reporter's Note: An earlier version of this story attributed Richard Hart's 1981 story to the Clarion-Ledger. It was reported in the Capital Reporter. We regret the error.

Top 10 Reasons to Support Locally Owned Businesses

- Local Character and Prosperity In an increasingly homogenized world, communities that preserve their one-of-a-kind businesses and distinctive character have an economic advantage.

- Community Well-Being Locally owned businesses build strong communities by sustaining vibrant town centers, linking neighbors in a web of economic and social relationships, and contributing to local causes.

- Local Decision-Making Local ownership ensures that important decisions are made locally by people who live in the community and who will feel the impacts of those decisions.

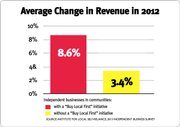

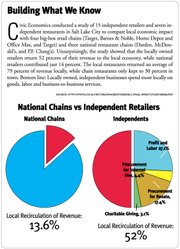

- Keeping Dollars in the Local Economy Compared to chain stores, locally owned businesses recycle a much larger share of their revenue back into the local economy, enriching the whole community.

- Job and Wages Locally owned businesses create more jobs locally and, in some sectors, provide better wages and benefits than chains do.

- Entrepreneurship Entrepreneurship fuels America's economic innovation and prosperity, and serves as a key means for families to move out of low-wage jobs and into the middle class.

- Public Benefits and Costs Local stores in town centers require comparatively little infrastructure and make more efficient use of public services relative to big-box stores and strip shopping malls.

- Environmental Sustainability Local stores help to sustain vibrant, compact, walkable town centers, which in turn are essential to reducing sprawl, automobile use, habitat loss, and air and water pollution.

- Competition A marketplace of tens of thousands of small businesses is the best way to ensure innovation and low prices over the long-term.

- Product Diversity A multitude of small businesses, each selecting products based, not on a national sales plan, but on their own interests and the needs of their local customers, guarantees a much broader range of product choices.

Source: www.ilsr.org