Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Photo by Trip Burns.

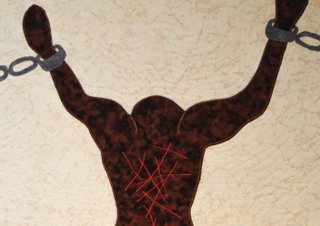

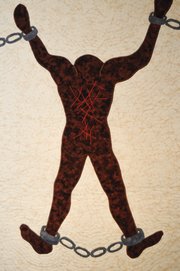

The image is stark. And shocking.

A black man, his ankles shackled, his head hanging away from the viewer, stands in relief on a field of white. Chains stretching to the image's borders on the left and right pull his arms taut. Fourteen crimson marks crosshatch his back. Within the dark fabric that frames "86 Lashes to Go," a small rectangle is labeled simply "salt."

"Plantation owners and overseers were often sadistic when they meted out punishment," fiber artist Gwendolyn Magee wrote about her piece. "Sentences of 50 to a 100 lashes were not unusual. And frequently even that was not enough—to inflict additional excruciating pain, salt was rubbed into the wounds."

Magee, who died in 2011, drew international acclaim for her striking quilts, which elevated an African and African American folk tradition to fine art. Her narrative pieces tell her people's stories of survival and brutality during 350 years as slaves in Magee's native south.

"Making quilts became one of the primary methods used by our grandmothers and great-grandmothers to try and keep their families warm when 'the hawk' came swooping through the cracks and crevices of the dilapidated shacks and shanties in which they were forced to live," Magee wrote. "It is the tradition of quilts like those that our 'Big Mamas' and 'Aunt Effies' so painstakingly made that is the essence of the medium through which I now visually represent their trials and tribulations and unfailing capacity for hope eternal."

The Mississippi Museum of Art is fortunate to include in its permanent collection several of the artist's story quilts, currently on display in "The Slave Series: Quilts by Gwendolyn A. Magee." Each piece layers rich, hand-embellished fabric to provide snapshots of startling reality.

In "You Ain't Go Be No Slave" a mother's arms hold a naked, squirming baby over a field of blue, the infant's mouth a surprised "O" as her head touches the water.

"Slaves didn't have a lot of control over their lives, but they did have some," Magee wrote about the piece. "This mother is in process of drowning her infant to prevent her from having to suffer a life of servitude."

Magee was unflinchingly honest in her art. In "Powerless," a black man sits outside his cabin door, head in hands, as white babies play at his feet. The door is ajar. Inside, portrayed in "Powerful"—the first in a two-panel piece titled "Powerful/Powerless"—a white man takes off his clothes as a naked black woman hangs her head. In "What the ..." across the gallery, a white man has dropped the gift of jewels he brings to his wife after the birth of a child—a swaddled cafe au lait infant sleeps in his crib, unaware he is the source of the white man's shock.

"Sexploitation of slaves by the Missus of the plantation happened infrequently, but it did occur and the 'chosen' one was damned if he did and damned if he didn't," Magee wrote. "However, unlike the Massa, the outcome was a little different for her if she wasn't careful."

"The Slave Series" is contained within the last gallery of a larger photo exhibit, "This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement." When you visit, walk through the many photos to see the quilts first. They will provide a larger historic context for the deeply affecting black-and-white photographs that portray the struggle against slavery's legacy in the Deep South. The region's harsh Jim Crow laws and exploitative sharecropping system echoed slavery's economics of servitude and poverty.

It took decades of determined protest and oceans of blood to achieve a semblance of equality for African Americans in a south where many whites still grimly cling to an ideology handed down through centuries of myth justifying dominion over all. In a photo by activist photographer Matt Herron, the arrogance and hatred is clear in the faces of the white Louisiana state troopers leaning on waist-height round sticks, taking a smoke break in Bogalusa, La., in 1965. "Later in the march, the tall trooper in the center used his club on the photographer," the placard states.

See "The Slave Series: Quilts by Gwendolyn A. Magee," and "This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement," through Aug. 17 at the Mississippi Museum of Art (380 S. Lamar St., 601-960-1515). Visit msmuseumart.org for more information.