Wednesday, January 15, 2014

Peaches Cafe is one of the few remaining businesses on Farish Street, which developers feel is primed to be the heart of a thriving entertainment district one day. Photo by Trip Burns.

Photo Gallery

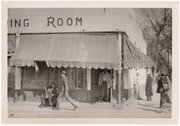

Farish Street in 1947

From Jackson State's Margaret Walker center, these photos by the late Charles C. Mosley reveal a different side of Farish street. We thank both Jackson State University and the Mosley family.

Most politically active citizens in Jackson are angry about something. Get them started, and you're in for a sermon. Popular topics for outrage include crime, low land value, the public education system and, of course, roads that have potholes big enough to sink a car.

But nothing rivals the level of disappointment over what has happened on Farish Street, the historic area on downtown Jackson's periphery designated as the future site of an entertainment district.

It doesn't make sense, thought, to talk about the Farish Street development project without noting the history of the area, one that is as illustrious as its redevelopment has been shameful.

At its peak from 1900 to World War II, the strip housed African American attorneys, doctor's offices, a bank, two hospitals and a dentist's office. During the oppression of Jim Crow Laws—which kept black residents out of many white businesses—commerce on Farish Street thrived.

By the 1950s and 1960s, civil-rights leaders started holding meetings in the Farish area's churches, restaurants and homes. Icons of the movement, including Stokely Carmichael and Medgar Evers, made the push for equality out of an NAACP office located at 507 N. Farish St.

When those men were successful, and Jim Crow was, at least on paper, kicked to the curb with the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the changes were remarkable for the black community. It didn't happen overnight—Mississippi schools didn't fully integrate until 1970, and Jackson didn't elect its first black mayor until 1997—but slowly, opportunities for minority-owned businesses to open shops downtown and in north Jackson emerged.

Farish Street was abandoned as customers moved elsewhere, with just a handful of businesses hanging on by a thread.

In 1983, Jackson architect Steven Horn came forward with a plan to renovate the area, and the push to revive Farish Street began.

The Early Tries

But nothing happened for two decades. Without a developer to take the reigns, the area sat nearly motionless.

In April 2005, Memphis development firm Performa and its president, John Elkington, picked up the stalled idea, promising Jackson an entertainment district that would rival Beale Street in Memphis. Elkington had cut his teeth luring big businesses to Beale during that area's renovation.

But Elkington's new Beale Street never happened. The way he tells it, Performa ran into problems with the Mississippi Development Authority and a state statute that outlawed alcohol sales near the expanded Mississippi College campus (which was resolved in July 2008 with a resort designation).

Elkington also told the Mississippi Business Journal in November 2013 that then-MDA President Leland Speed, who later retired in late 2012, demanded that Performa add residential apartments. He said Watkins got involved in the project first as a lobbyist working to get the resort status in place.

But even with resort status, the project stalled. The JFP reported in 2008 that Elkington was facing problems getting a bank loan, even though MDA was guaranteeing it. That angered Downtown Jackson Partners President Ben Allen, who was pushing for Farish to be Jackson's version of Beale.

At the time, Allen hinted that forces out of Performa's control were blocking the project: "There's a whole lot I'd like to say about it, but many of us are working hard to get this resolved, and I don't want to fan the flames in any way, shape, form or fashion. We're just trying to get it done," Allen told the Jackson Free Press then.

By October 2008, Performa was out, and the newly formed Farish Street Group took over, generating renewed hope because of chief investor David Watkins. He was known for his push for renovation of the historic King Edward Hotel and Standard Life buildings, both of which were still undergoing renovation at the time.

They are now fully operational and breathing life into downtown Jackson.

That momentum didn't carry over to nearby Farish, though. The strip does have one nightclub, Frank Jones Corner (commonly referred to as F. Jones), open at the corner of Farish and Griffith streets, and a small handful of legacy businesses hanging on, but none of that was Watkins' doing.

The Farish Street Group's plans included 13 venues on the stretch of storefronts from Amite Street to Griffith Street, but the future of those buildings is once again unclear. Watkins had hoped to have a B.B. King's Restaurant and Blues Club open on the street by the end of 2012, but after architects finalized designs for the club, engineers discovered that the structure was not capable of supporting the capacity load. In fact, the building didn't even have a foundation.

The Jackson Redevelopment Authority cancelled the lease with the Farish Street Group Sept. 25, 2013.

Now, Farish Street Group, Watkins and the JRA are embroiled in a legal battle so tangled it could take years to clean up. Watkins placed liens on the buildings he was working on when JRA terminated his lease, and the JRA is suing Watkins for placing those liens. Not to be left out, the Central Mississippi Planning and Development District and the Mississippi Development Authority, two agencies with money tied up in the project, are both urging the JRA to reinstate Farish Street Group's lease until the parties can reach a more-amiable divorce agreement.

Two circuit-court judges have already recused themselves from the case, and both sides have logged hours of deposition.

The legal situation will eventually sort itself out, but what will happen to Farish? After 25 years, millions in investment and hundreds of hours of discussion, we're still left with more questions than answers: What does Jackson need out of the district? What will work? What kind of a role does race play? And maybe most importantly, who's going to get rich, and who is going to be left holding the bill?

Even with the adversity, the turmoil surrounding Farish could give Jackson an opportunity to hit the reset button and assess the situation—and maybe even have a conversation about what the aim of the project should be going forward.

What Won't Work?

Watkins wants to develop Farish Street as an entertainment district, which many developers and city leaders agree Jackson still needs. But should historic Farish Street turn into a tourist trap like Beale?

VisitJackson.com, a website run by the Jackson Convention and Visitors Bureau, states that "Farish Street is to Jackson what Beale Street is to Memphis and Nelson Street is to Greenville."

The comparison is easy to make.

Beale Street was once a lot like Farish. In the early 1900s, it was filled with many African American-owned clubs, restaurants and shops. NAACP co-founder Ida B. Wells co-owned and edited an anti-segregationist paper called Free Speech there, and Beale Street Baptist Church, built in 1864, served as a meeting place for black leaders during the Civil Rights Movement.

Like Farish's, many of Beale's businesses shuttered their doors in the late 1960s and early '1970s. The street sat lifeless as a ghost town before developer John Elkington, who is white, worked with city officials, preservationists and investors to turn the area into a thriving entertainment district.

A walk down Beale Street reveals a bustling community of nightclubs, blues bars and restaurants, with tourists walking from business to business carting big, green plastic alien-shaped drinks. Tennessee's self-proclaimed top tourist attraction is full of tourists, and while it retains some of its history, much is papered over.

A 1998 New York Times piece by Brian Knowlton noted the stark difference between the old Beale Street and the freshly refurbished entertainment district.

"The faces in Beale Street are now more white than black," Knowlton wrote. "While 40 percent of new businesses are owned by blacks, white-owned venues, including a Hard Rock Cafe, dominate."

Knowlton talked to Beale Street photographer Ernest Withers, who became famous for his black-and-white images of the segregated south before his death in 2007. "I'm old enough and wise enough to know that nothing lasts forever," he said. "The street's not what it was. It's something else now, and you just got to take it as it is."

Today, the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce member registry lists one minority-owned business on Beale Street: the Black Business Association.

"There are a few others," Black Business Association of Memphis President and CEO Roby S. Williams told the JFP in an interview. "There's a place called Eel Etc. Fashions that is doing pretty well, they've been there almost longer than anyone else, and of course, there's B.B. King's."

B.B. King's, named for the legendary bluesman and Itta Bena, Miss., native, was also set to be the anchor venue for the rest of the two blocks of Farish, from Amite to Hamilton streets, originally set to become the entertainment district.

Williams, who grew up in the Beale Street area, said he remembers when the area was the economic powerhouse for the black community in Memphis.

"When I was a kid, Beale Street was cookin', and it was black folks," he said. "Now you go down there, and the busiest places are stuff like Hard Rock Cafe and out-of-town chains."

That a similar trend could start on Farish is a real concern in Jackson, where 72.2 percent of the city is non-white, but only 44 percent of the city's businesses are minority-owned.

Likewise, Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba roundly rejects the idea of gentrification—a shift in an urban community toward wealthier residents and/or businesses and increasing property values, sometimes to the detriment of the poorer residents of the community.

In his inaugural speech on July 1, 2013, Lumumba said he regarded the gentrification of urban communities as "nothing more than a war on the people who already live in the community." Typically, areas around districts such as Beale become pricier to live in—thus gentrifying out poor people and often people of color.

While the Farish Street plan might have originally involved a lot of local businesses relocating to the two blocks of Farish from Amite to Hamilton streets, some argue that the Farish Street Group installed roadblocks that priced out at least one business.

Geno Lee, who owns and manages the historic Big Apple Inn, said the financial benefit of moving his business did not outweigh the initial steep costs.

Despite the fact that Big Apple Inn has been black-owned and on Farish for 75 years, Lee said Watkins quoted him such cost-prohibitive prices that it would have been easier to open a location on County Line Road or at the Renaissance in Madison, two areas on the periphery that have already established high commercial value.

"They told me it would cost $300,000 up front for an 1,800-square-foot space, and then I would pay nearly $25 a square foot for rent," Lee said. About half of that was the actual price for the Big Apple Inn to move in, and the rest to pay for building improvements, including air-conditioning repairs.

"There's no way I could afford to do that. For comparison, they are leasing space as low as $10 per square foot on County Line, and the one-time fee to get into Renaissance isn't anywhere near $300,000."

Lee said that Watkins told him that those prices were comparable to rents on Bourbon Street in New Orleans and Beale Street in Memphis. In talking with the folks from the Renaissance in Madison, Lee said he's found their price for rent to be not just comparable, but cheaper than Farish Street.

"It's crazy," Lee said. "But maybe that's why that area is successful. They aren't pricing themselves out of the market and not gouging the businesses that move in. And people wonder why a lot of economic development is moving out of Hinds County."

But Farish Street isn't anywhere near where those entertainment districts are, at least not in terms of foot traffic and commercial appeal, and it may never be. After running the numbers, Lee said he just couldn't pull the trigger.

"There were club owners and restaurants that were ready to take the plunge and try to make it down there," Lee said. "But to make the prices something we couldn't touch, I have no idea why they would do that, unless they had another agenda."

When Lee responded by saying the asking prices were too high, and that it would price him, and many other businesses out, the response from Farish Street Group, he says, was unnerving.

"There was no negotiation," Lee said. "They basically said, 'That's too bad.'"

Watkins, through his attorney Lance Stevens, said this week that he is sticking by what he said in a 2011 JFP article by reporter Adam Lynch on the same topic, and declined comment for this story.

"We can't afford to have any clubs that don't really generate a lot of money and attract a lot of traffic and customers," Watkins told Lynch in February 2011.

"...[A]ll of the developments have to be at a high level of quality, and all of the developments have to be approved by (the Department of) Archives and History."

Because development of the district must conform to expensive building standards set by the Department of Archives and History, Watkins said, the resulting real estate is some of the most expensive in the state.

"Every lease has its own build-out provisions," Watkins said. "We end up with so many governmental approvals that you have devils in the details."

What Will Work?

The good news for folks who oppose turning Farish Street into a place where you can have a Beale Street-like experience is that the comparison between the two streets ends at the history.

"What has benefited Memphis in building Beale Street is that, aside from being a bigger city, they started much earlier on the renovation than we did," Director of the JSU Center for University-Based Development and former JRA Executive Director Jason Brookins said.

"It was developed over a couple of decades. New Orleans created Bourbon Street over a couple of decades. We can't start now in the same place those communities started. It's going to take a multi-year plan.

"But if we're being honest, we don't want in the heart of our downtown, in between downtown and a residential area, a Bourbon Street or Beale Street. It needs to be our own kind of thing. It could be family-oriented, but still have some nightlife for the young people. It could have pockets of a lot of things. It needs local flavor, and local people."

Watkins' vision of Farish was one of a big anchor, B.B. King's, and several other smaller clubs, including Funny Bone Comedy Club, daiquiri bar Wet Willie's and the King Biscuit Cafe, a blues club. But the Farish Street Group was going to have to spend big money to fix the building set to house it. He has said B.B. King's wasn't going to come in if it was going to be the only club. It was only interested in installing a location if it was going to part of an entertainment district.

If Watkins returns to the project after the legal battle ends, it stands to reason that his vision will return with him.

Local attorney and former JRA board member John Reeves said in a recent interview with the JFP that if anyone can make the project work, it's Watkins, because he's involved for the right reasons, Watkins, he said, has a vested interest because he has already was the public face of two projects in the area: the King Edward Hotel and the Standard Life Building.

"At the time (that the took on the Farish Street lease)," Reeves said, "I told him, 'I don't know why you're doing this.' Honest to goodness. Performa couldn't get a single local or state bank to put a penny in it, and he was going to have to beg for tax credits and get investment from out-of-state banks, because when local people start running the numbers, they can't make it work on paper."

The work of finding a new developer will be tough, Reeves said, especially considering the lengthy court battle that is ramping up now.

"David would still want to do it," Reeves said. "He's an optimist like that. I think they should let him have it, but honestly I don't know why he'd want it. Most successful business people would agree that Farish Street lease is a liability, not an asset."

Et Tu, Alternatives?

If Reeves is right that the current Farish lease is a liability, it could mean that Jackson should rethink what we want out of the historic Street.

Local businessman Malcolm Shepherd, who grew up on Farish Street and at one time worked for the Jackson Advocate, a black newspaper in Jackson, recently parted ways with development company Full Spectrum South to return to work full time for his own company M&M Services. He said in a recent interview with the Jackson Free Press that perception is a big problem when trying to get funding in Jackson.

Shepherd worked on the Old Capitol Green project—a stalled plan to develop the area around the warehouse on Commerce Street that houses Hal & Mal's into a shopping and entertainment area—until the Hinds County Board of Supervisors denied the next phase of funding in late 2013.

He said that, in lieu of big-money investors, whomever the Farish Street developer ends up being should take a local approach. To that end, he said he encouraged his friend, and former Green Party gubernatorial candidate, Sherman Lee Dillon, to open F. Jones Corner at the intersection of Farish and Griffith Streets, which he did along with his son Daniel Dillon and family friend Adam Hayes in 2009.

F. Jones has made it, Shepherd said, because it's the only game in town when it comes to Farish. "They aren't making a million dollars a month," he said. "But they are doing alright. So what if we get a couple of other local investors to open other old bars up and down the street. I'm talking about the Crystal Palace Ballrooms and Birdlands of Jackson's past. People would remember and go to those places."

Brookins also points to F. Jones Corner as a source for optimism.

"The benefit of doing it in that area is that the JRA already owns the land. That should expedite things. It's also an easy spot for tourists to frequent. It's got the theme of Mississippi talent, homegrown talent. The Mississippi Development Agency and the Department of Tourism both recognize it as a key stop on a tour of Mississippi's birthplaces of American Music.

If the city embraces tourism as a major economic engine, Brookins said, then Farish could become unique among entertainment districts, and serve as a showcase for what Mississippi has to offer visitors to the state.

"You do want local people, because that ties you into local investors," Brookins said. "When you bring in a national chain, so much goes back out of the community. ... We've got to sell it, and it's got to be a part of the national narrative. It's got to be a global discussion, and everyone in the state has to buy into it.

"We could have food from the coast, and music from the Delta and north Mississippi. This is the capital city, and it makes more sense for us to have an entertainment district where people can taste a piece of the rest of the state. We'll consider it their first blush at us."

What Role Does Race Play?

One telling aspect of the Farish Street saga is this: In the entire revitalization process, not one private bank has extended credit to anyone to invest in the project.

The Mississippi Development Authority has put $4.7 million in through the Central Mississippi Planning and Development District, and Watkins invested $4 million, but there have been no bonds, no loans and no private investors.

Local developers and businessmen point to two reasons behind that.

First, Reeves pointed out, is that there's a perception that the project is doomed to fail. Businessmen, he said, are looking to make viable investments that have a great shot at succeeding and being successful.

"If the Farish Street project can't stand on its own economically, it shouldn't be done," Reeves said. "If it doesn't make sense on paper, it's going to be near impossible to do it. Let's say you build a restaurant and bar on Farish Street. Is a couple that lives in Brandon going to scratch their heads at 6 p.m. on a Friday and say, 'Let's go to Farish Street and get a bite to eat?' The answer is no.

"Look at all the development in the outlying areas. You've got Madison Crossing, The Outlets of Mississippi (in Pearl). The Farish Street development isn't happening any time soon. I'd like to see it work. I'm sure it'd be wonderful, but it's only going to happen if a businessman can look at a balance sheet and see where he is going to make a profit. People don't open businesses unless they think they can make a profit."

Shepherd suggested that the motivation behind the non-investment is due to archaic thinking around investing in majority-black areas of the region. He called the perception of Jackson as a base of operations among state business leaders "outdated."

"People are real conservative from a historical perspective," Shepherd said. "It's ingrained in some of them. We've got support from the (Jackson Convention and Visitors Bureau) and the state tourism department with the blues markers and things like that. That's free help. To not take advantage of that, I think, is a reflection of people's attachment to their historical perspectives.

"They can't see the viability of this area, because they never invested their intellect. It's like keeping blinders on, because you can't recognize that the market has changed. Well, change is coming whether you want it or not, and in fact, it's already here. Diversity is what you need."

Shepherd compares the neglect of the African American community as an empowered financial consumer group to the way college-age kids were once perceived—where once students were thought to have little-to-no buying power, today their needs are driving the narrative of development.

"The powers-that-be finally realized that the students are the ones that are going to these venues and supporting the restaurants," he said. "They are the ones calling for bike lanes and complete streets. It just goes to show you that we have been drug into the 21st century kicking and screaming."

That perception is slowly changing, he said, thanks to developments on Lynch Street near Jackson State University and the growth around the Mississippi Medical Mall. "A new grocery store moved in, and now there's a Walgreens there," he said. "It's happening; it's just happening slower than these projects in Madison and Pearl and Flowood because there's not big money behind it."

When Elkington had the lease on the project, the Jackson Advocate reported that Beale Street had been built with little minority participation, and tried to dissuade city leaders from allowing the same thing from happening on Farish Street.

So did things get any better when Watkins and the Farish Street Group came on board? "Hell, no," former Jackson Advocate writer Stephanie Parker-Weaver said. "We never had a problem with (Watkins) personally, and I think he's a very pleasant, nice guy. But development-wise he started becoming a Leland Speed-type developer. (Watkins) had made a bunch of money as a lawyer for the JPS board, and he was able to take on projects and develop, which was great, but he continued, and continues to feed out of the public trough."

Speed rebuked that indictment Tuesday morning by phone, noting that he worked as head of MDA for four years without receiving a pay check.

Parker-Weaver would prefer to see Farish developed in a more grass-roots way with more taxpayers benefitting. "Public dollars shouldn't be used to line the pockets of already-wealthy people. The needs are too great: housing, street resurfacing, water and sewer. Instead, those Community Development Block Grant funds, which are supposed to be for the poor, end up going to development projects."

See jfp.ms/watkins to read more about the current legal problems plaguing Watkins and the Farish Greet Group.