Wednesday, November 11, 2015

Mississippi House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton, spoke against Initiative 42 at a press conference in Hattiesburg on Oct. 22. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

As soon as the Mississippi Legislature proposed an alternative measure to Initiative 42, a citizens' initiative to fully fund the Mississippi Adequate Education Program, its advocates cried foul, saying the alternate was only there to confuse voters. But the alternative-initiative gambit worked whether it was a meaningful amendment or just a legislative trip-up for voters. While the alternate amendment itself did not win, the two-part question, including 42-A, on the ballot undoubtedly confused some voters on Nov. 3.

By Mississippi constitutional standards, the Legislature was fully entitled to propose an alternative measure to a citizen-driven ballot initiative—that's in the constitution. The unraveling of Initiative 42 began in the Legislature itself in the 2015 session, when the Republican leadership backed a bill that Rep. Greg Snowden, R-Meridian, sponsored in the House of Representatives that suggested alternative measure 42-A.

At a press conference on Oct. 19, Snowden said that the Republicans moved quickly to add an alternative because of what they perceived to be the danger of Initiative 42 passing. Snowden said Initiative 42's proposed constitutional amendment was "completely contrary to our system of representative democracy," from power it supposedly passed to the judiciary branch to removing the word "Legislature" from the constitutional provision, which the Legislature made sure to keep in 42-A.

From the outset, the Republican leadership's campaign message to stop Initiative 42 from passing was not "Vote for 42-A" but instead "Vote No on 42."

Power and Control

Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson, said that those who created 42-A did not support their own language. By proposing 42-A, those legislators were also proposing a different constitutional amendment—something they rarely mentioned. Initiative 42-A would have amended the state constitution as well keeping the Legislature responsible for public-school funding. It would have changed Section 201 of the constitution to say, 'The Legislature shall, by general law, provide for the establishment, maintenance and support of an effective system of free public schools." The Republican leadership seemed most concerned with squashing Initiative 42, however, and not amending the constitution itself.

At an October press conference before the election, House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton, focused on the language that Initiative 42 would add to the Constitution.

"I want to show you what Initiative 42 proposes to do: If you look at the first change made in the constitution, (it's) the deletion of the words 'the Legislature,'" Gunn said at a Hattiesburg press conference.

At the same gathering, Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves said Initiative 42 was a vote about power and control, not education funding, pointing again to the constitutional language.

"The proponents of 42 would have you believe that this is about funding, but if you look at the changes they propose in the constitution, the word 'funding' is nowhere to be found," Reeves said.

The Republican leadership harped on the Initiative 42 language but rarely, if ever, promoted 42-A's ballot language. Blount said they were disingenuous, for this very reason.

"From early on, the mixed messages sent out by the opponents of 42, namely 'We don't want to amend the constitution,' (were contradictory to what 42-A is)," Blount said.

The anti-42 campaign sent out mailers and flyers encouraging voters to vote "Against Both" and in favor of "42-A," a vote that in and of itself is incongruous, because voters who vote against a constitutional amendment do not have to choose which one they want.

Ballot of Confusion

Patsy Brumfield, the spokeswoman for Better Schools, Better Jobs, said the alternate measure was designed to ensure a "difficult-to-understand ballot" and erect another barrier against Initiative 42.

If the vote had been a straight "Yes" or "No" on 42, which is what the ballot would have looked like without the alternative, it might have turned out differently, Brumfield said.

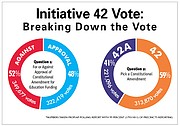

The ballot totals for the first question, on whether to amend the state constitution, asked voters to vote "For Approval of Either" or "Against Both."

It received 672,096 votes, with 52 percent of those voters choosing "Against Both"—blocking any constitutional amendment from passing.

The second question asked voters to pick between 42 and 42-A. If a majority of voters (50 percent plus one vote) had chosen to amend the constitution, then the second question would come into play, with two caveats.

First, either 42 or 42-A had to garner a majority of the votes. Second, the winner's vote tally had to be at least 40 percent of total votes cast in the election.

If voters had understood the way the ballot was structured, then there should only have been about 322,420 votes for the second question—the number of people who voted "yes" on amending the constitution. However, the second question drew 534,966 votes total, with Initiative 42 drawing the most with 59 percent of the votes. The Mississippi Constitution allows those who vote "against both" measures to still vote on the second question, even though they do not want to amend the constitution.

In fact, Initiative 42 won the 40-percent overall majority of total votes cast in the election that would have been required for the ballot initiative to pass, as prescribed in the Mississippi constitution.

Brumfield said the first question likely confused some people, who skipped to the second one because they recognized the number 42.

"I think the configuration of the ballot ... really threw a lot of people," Brumfield said. "They didn't know what to do with that first question, so I think they went down to that question they knew what to do with."

Despite Initiative 42's failure, Brumfield said she believes supporters of 42-A still support public schools.

Sen. Blount agrees.

"I know there are a significant number of people who voted against the constitutional amendment but want the Legislature to fully fund MAEP," Blount said. "I think all legislators need to look at the results carefully."

'We Have Roofs That Leak'

Initiative 42 and even 42-A brought Section 201 of the Mississippi constitution into focus, particularly the issue of education funding.

MAEP, the formula that calculates the Legislature's contribution to public-school funding, has only been fully funded twice since its creation in 1997.

Before the election, Rep. Cecil Brown, D-Jackson, who served as the chairman of the House Education Committee and was just elected public-service commissioner of the central district in this election, said he was not convinced that lawmakers campaigning against 42 are going to fully fund MAEP.

"These folks are not going to fully fund education," Brown told the Koinonia Coffee House Friday Forum audience on Oct. 30, days before the election. "We've got 500,000 kids in public schools. The problem is we have roofs that leak; we don't have textbooks; we don't have computers."

MAEP funds the base of the educational system, paying for teachers, staff, and the buildings and facilities that make the public-school system work. With underfunding, most of the formula's funds end up paying for teacher salaries and raises. Brown believes that Republican leadership is going to shrink MAEP or change it in order to "fully fund" it in the upcoming legislative session.

"They will change the formula, so they can magically fully fund it, and all of a sudden, MAEP will be 'fully funded' with no (additional) money," Brown said in an interview.

Lt. Gov. Reeves did not mention changing the formula when asked about it in October. He said he will support full funding, however.

"I'm for fully funding MAEP for a slightly different reason than some other folks," he told the Jackson Free Press at a press conference in Hattiesburg. "I want to fully fund it because I want to take the excuse off the table."

Sen. Hob Bryan, D-Amory, who was re-elected for another term, said legislators should not tamper with the formula, and if the election results prove anything, they show that 48 percent of the people are for the formula. Bryan said the Senate Democrats have been pushing for fully funding MAEP in the past two legislative sessions, suggesting a three-year phase-in, and will continue to do so in the upcoming legislative session.

"The Senate Democrats have had a very legitimate, conservative budget proposal where we could fully fund the adequate-education formula in three years and have corresponding increases in three years for universities and community colleges," Bryan said.

The plan, Bryan maintains, does not come from a tax hike or from additional taxes, but instead from revenue coming into the state coffers that has been moved to other parts of the state's budget in past years—particularly tax cuts for corporations and businesses being wooed to Mississippi. Bryan said campaigning against the state income tax seems more important to Republican leaders than funding public schools.

In this past election, Republican leaders campaigned on their education funding, and Reeves acknowledged that the formula had not been a priority—but say that hiring reading coaches and improving literacy have been.

"If all we cared about was the politics, we would have already funded it, but instead of investing every penny we're investing on K-12 in the formula, we're actually doing things to help kids," Reeves said in an October press conference against Initiative 42.

'All Hands on Deck'

Sanford Johnson, deputy director at Mississippi First, a group that advocates for policies and solutions to increase educational attainment in the state, said the "how" of public-school funding got lost in the Initiative 42 campaign. The general public, he said, has the responsibility to stay informed and involved in the issue now that the initiative has failed.

"We have to have these conversations about equity and accountability," Johnson said. "'Are we spending our money efficiently? How much money does it actually cost to educate a child?'"

Johnson said the approach to education in Mississippi going forward needs to be "all hands on deck," focusing on not just fully funding the MAEP formula but also boosting reading achievement and expanding access to pre-kindergarten as well.

"We don't have time to focus on one (element)," Johnson said.

"We need to be working on more than one thing at a time."

Initiative 42's demise means that planning for education funding now lies in the hands of all the legislators elected Nov. 3—a GOP-controlled Legislature.

Nancy Loome, executive director of the Parents' Campaign, strongly encourages engaged Mississippians to reach out to their legislators and make sure they are representing their communities' desires to fully fund public schools.

"It's incumbent upon us to make sure that they know what we want to have happen," Loome said. "They can't represent us well if they don't know where we stand."

Loome said that so many voters weighing in on 42 and 42-A shows that Mississippi taxpayers want public schools adequately funded at least, and that it is time for the Legislature to start listening and do something about it. When the Republican leadership talks about their "record-level" school funding, Loome said the funding they tout does not directly benefit all school districts.

For instance, the funding for reading coaches (which is not a part of MAEP) helped hire around 72 of them, Loome said, but those coaches could not possibly reach all the schools—in fact, that's only one coach per every two school districts in Mississippi.

Next Stop, Vouchers?

Grant Callen, executive director of Empower Mississippi, a school choice advocacy group that campaigned against Initiative 42, said that voter turnout showed that at least those who voted agree that the educational system in Mississippi is not working.

"How to solve it (the system) is a point of debate—and how to fix it," Callen said. "I see a majority of people who do not think that money is the answer to our education system."

Callen says the formula itself is problematic. MAEP is setting the bar high because even when state revenues are at all-time highs, the formula can't be fully funded, he said.

"That tells you something is wrong with the bar," Callen said.

Potential education funding plans from the Republican leadership could include tampering with the MAEP formula, or broadening voucher laws that would give parents a voucher to use for a private school instead of their child attending public schools.

Loome believes neither strategy would benefit public schools, siphoning funds away from where they are needed most. Callen disagrees, saying he would love to see the special-needs education voucher bill, which Empower Mississippi fought for, expanded to the entire student population.

"We think every kid in the state who is in a situation where the public schools are not serving their needs ought to have the ability to have an education scholarship account (voucher) so their parents can customize an education that meets their needs," Callen said.

Last session, Sen. Gray Tollison, R-Oxford, proposed changing the "Average Daily Attendance" component in the MAEP formula to "Average Daily Membership." The change could have potentially bolstered school-attendance numbers used to allocate funding per district by taking a year-long average of attendance in schools instead of counting students in September and October. However, other proposals like those found in Auditor Stacey Pickering's report on MAEP suggest that the formula itself is ineffective.

"You hear people say they don't like the formula, but you don't hear them say what they don't like," Loome said. "But they are going to find it difficult to come up with a different formula that is both adequate or equitable."

Some legislators are confident that the Republican leadership is going to continue to push voucher legislation in the upcoming session, trying to divert potential MAEP dollars toward voucher accounts to allow families to transfer their tax dollars away from public schools.

Callen, who said the Republican leadership that was re-elected does care about education and spending more money on it, argues that vouchers will allow families to have more choice in their child's education, a key goal for his organization.

Bryan said the Republicans' overall strategy is to replace public education with vouchers. As for the public's role in education funding in the future, Bryan echoed what Loome and Johnson said.

"The public needs to demand funding, and not stop demanding it," he said.

Judicial Remedies, Still?

With the defeat of Initiative 42, education proponents wanting to strong-arm the Legislature into fulfilling its own mandate to provide adequate school funding still have a glimmer of hope in one pending lawsuit in Hinds County.

The case started last August when former Gov. Ronnie Musgrove filed suit on behalf of 14 Mississippi school districts (five more plaintiff districts eventually joined) against the state. The goal was to recoup millions those districts say they were shortchanged as a result of the state ignoring MAEP, the formula created in 1997 to provide a baseline of funding for all school districts but that the Legislature has ignored all but two years since.

In 2006, legislators passed a bill to require full funding by 2010 with a phase-in period between 2007 and 2009. Since 2010, Mississippi has underfunded public education by $1.5 billion. Collectively, the districts Musgrove is representing—now totaling 19—are seeking more than $240 million they said they were shortchanged during six state-budget years.

The suit suffered an initial setback in July when Hinds County Chancery Judge William Singletary ruled against the districts, writing in his opinion: "This court is sympathetic to plaintiffs' untenable position of being required to educate the students of Mississippi with less than a fully funded MAEP. However, this court is unable to interpret the relevant statutes as imposing a mandatory annual duty on each legislator to automatically vote to apportion and allocate to each district 100 percent of the funds estimated under MAEP."

Singletary subsequently allowed Musgrove to make a fresh round of arguments in mid-October, but had issued no new ruling as of press time. Gov. Musgrove said his clients would appeal if Singletary doesn't reverse his July order. (He also expects the state to appeal if the judge does reverse the ruling.)

Musgrove said the 2006 law is unambiguous, saying that lawmakers "shall fund" MAEP. If lawmakers believed they did not have a responsibility to fund the formula, he questions why they have not eliminated it.

"There is nothing right now keeping the Legislature from amending the MAEP statute, and they chose not to," Musgrove told the Jackson Free Press in an interview.

Even if the Legislature scraps MAEP, Musgrove said his clients would still deserve the money they were shorted because, he argues, lawmakers have an obligation to fully fund MAEP until they decide to change it.

Matt Steffey, a constitutional law professor at Mississippi College School of Law, said even though the "one Hinds County judge" meme of Initiative 42 opponents is a red herring, courts are a tough place for public-education litigation unless constitutional issues are present. Initiative 42 sought to amend the constitution specifically to give the courts more power to enforce school-funding laws.

"Funding decisions are discretionary," Steffey said. "Under the principle of legislative sovereignty, every time the Legislature opens for session, it's a new sovereign; it's a new day. One Legislature can't really bind another one if that Legislature decides that the money isn't there or shouldn't be allocated in that fashion."

Besides, Steffey adds: "Courts aren't designed to make decisions about what's adequate (or) what's efficient because, like beauty, that's in the eye of the beholder. Those words imply discretion so I've always thought that if (Initiative) 42 passed, judicial intervention would be limited to extreme cases—no textbooks, not enough money to hire a first-grade teacher."

A federal civil-rights challenge, for example, would face similar obstacles in part because the Legislature created MAEP to address equity issues. A successful federal lawsuit would have to prove intentional, overt race discrimination, which has become increasingly rare since the 1970s.

"There is no readily apparent judicial remedy. That isn't to say there isn't one, but there is no easy way to force the Legislature to fund your school," Steffey said.

Read more about Initiative 42 and MAEP at jfp.ms/maep. Email reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected]. R.L. Nave contributed to this story.