Wednesday, September 2, 2015

Yolanda “Lala” Kirkland has been at Stewpot Neighborhood Children’s Program for 17 years, working with homeless middle and high-school students to make sure they graduate high school and, hopefully, college. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

Shamberi Horton found the after-school program at Stewpot Community Services through a friend in seventh grade. A big bus came to her middle school to pick up kids at the end of the school day, and Horton got curious.

"My friend told me to just get on the bus," Horton said. "So I got on the bus—I was ready."

Yolanda "Lala," Kirkland called Horton's mother to tell her that her daughter had shown up unannounced, but from then on, Shamberi and her sister were allowed to get on the bus every day after school.

Horton was not homeless growing up, but she was raised by a single mother and understands the importance of having a program for children to hold them accountable for their schoolwork.

Now Horton, 29, leads the elementary-school side of the after-school program., while Kirkland, who has been with Stewpot for 17 years, leads the middle and high school side. Horton's students grow up and go to Kirkland's building when they get to middle school. Horton said she makes sure to fuss at them and check in on their progress. "I know what they're capable of," she said. "It takes a village."

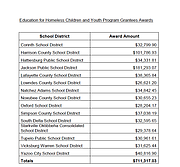

Stewpot Community Services is one of several programs that serve homeless youth in the Jackson area. More than 3,000 students in Jackson Public Schools are homeless. Services for those students should improve in the coming year because the Mississippi Department of Education has approved additional federal funding for homeless youth in 15 school districts, including $181,290 going to JPS.

The funding comes from the federal McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program. Fifteen school districts will receive more than $23,000 per district depending on the needs and number of homeless youth. The grant lasts 15 months and can go toward tutoring needs as well as medical, dental or mental-health services that homeless youth likely cannot access on their own. The state will reimburse districts monthly.

"We can't do anything about what's going on at home, but we can make sure academically you can stay strong and that you become a successful adult," Kirkland said.

The Stewpot Neighborhood Children's Program currently serves 88 students from kindergartners to high-schoolers, primarily students who live in shelter programs through Stewpot, with the goal of helping them graduate from high school. Not all the students in the program are homeless; it is open to all students and completely free, so the staff relies on JPS to provide tutors and counselors to students. Depending on how JPS allocates its additional funding, Stewpot might be able to serve more students with more tutors and support from JPS.

Engaging with homeless families can be difficult, but the end result makes it all worth it, the staff said.

"Getting those parents engaged can sometimes be difficult because they have other issues: no home, no food, no clothing," Kirkland said.

Stewpot Neighborhood Children's Program started in 1991, and the after-school tutoring program in 1997.

Initially, the program struggled as kids would leave and never come back, but as the program grew, so did the consistency of the staff and students alike.

Academics are difficult for homeless students because they are often moving and sometimes already behind a grade level with nowhere to get the homework help—or motivation—they need.

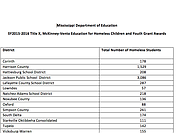

Marcus Cheeks, the director of federal programs at the Mississippi Department of Education, said there are more than 10,000 homeless students in the state.

"Homelessness is a real barrier," Cheeks said. "If a child doesn't have a regular nighttime residence to deal with their regular social needs, that rolls over into the school and not (being) able to focus on the regular academics of the day."

The Mississippi Department of Education is required to track the amount of homeless youth in the state in order to receive Title I funding and now the McKinney-Vento funds. School districts give their numbers to the department each month, but the districts can only do so much with the money; often middleman organizations like Stewpot's after-school program must supply the actual services.

Congress passed the McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Assistance Act in 1987. The federal funding is conditional, and the states must agree to the conditions set by the U.S. Department of Education to receive funding.

At Stewpot, students' families have access to shelters, health care and other services that schools cannot provide for homeless youth, although JPS can supply tutors.

The Stewpot Neighborhood Children's Program works largely because of the relationships the staff builds with the kids' parents, Kirkland said.

If kids in the program are homeless, it's likely because their parents are homeless, so maintaining relationships with parents to keep track of the kids is crucial.

The staff consists of four women—Lesley Collins and Horton work with the elementary-school students, while LaQuita White and Kirkland work with the middle-school and high-school students.

Students take buses or get rides from the staff after school and come to two buildings in the back of the Stewpot Community Services complex. There they work on homework in a structured environment, with tutors from JPS and the Stewpot staff. The program for middle- and high-school students helps them get ahead on schoolwork, providing materials for bigger projects if needed.

The program is continuously taking students in, and the model works largely because when a child comes in, he or she is in for good.

"Once you're a Stewpot baby, you're always a Stewpot baby," Collins said.

The program hinges on the belief that graduation is a child's ticket out of homelessness. The first question Kirkland asks students she hasn't seen them in a while is "Where's my diploma?" After graduation, the Stewpot team encourages students to go on to college and get a job.

Kirkland and White have graduated all their students in the past six years.

Cheeks said eight of the 15 districts that will receive the funding are lower-performing districts. The school districts receiving grants are: Corinth, Harrison County, Hattiesburg, Jackson, Lafayette, Lowndes, Natchez Adams, Noxubee, Oxford, Simpson, South Delta, Starkville Oktibbeha, Tupelo, Vicksburg Warren and Yazoo City.

Number of Homeless Youth by CITY-County Receiving McKinney-Vento Grants

Jackson Public Schools: 3,086

Harrison County: 1,529

Yazoo City: 335

Lafayette County School District: 287

Simpson County: 261

Natchez-Adams School District: 218

Hattiesburg School District: 208

Corinth: 178

South Delta: 174

Vicksburg-Warren: 155

Tupelo: 142

Noxubee County: 136

Starkville Oktibbeha Consolidated: 111

Oxford: 88

Lowndes: 57

*Data from the Mississippi Department of Education. The 2014-2015 Consolidated State Performance Report indicates that 10,131 students in the state are homeless.