Wednesday, April 20, 2016

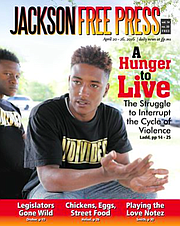

Linda Knight grew up poor in the Washington Addition and got out as soon as she could, even if it meant a life of prostitution and leaving her son behind and, eventually, crack addiction. Throughout it all, though, she pushed her children to get a good education. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

JACKSON — Linda Knight was only 18 when she snuck into the Afro Lounge on Lynch Street one night in 1973 and met the man who would take her out of the Washington Addition. Sitting in her easy chair in the small house she now owns on Hill Street, where she looks out the front door at the Lincoln Cemetery, she laughs when she remembers how much that mystery man excited her. He was unlike anyone she had ever met, growing up in a poor, strict Christian home on Dansby Street, where her parents wouldn't let the kids leave the yard, and her mother traveled to Whitfield every night to work as an intake clerk.

"He was so handsome. He was from another world," she says, cackling at the memory behind her dark-rimmed glasses. She wasn't so bad herself, a beauty, tall like her son John Knight is now.

"Y'all want a ride?" the man asked her and her best girlfriend.

They slid into his white convertible El Dorado with white leather seats and a sassy red dashboard. They dropped her girlfriend off and continued on to where he stayed out in Hinds County where a certain amount of debauchery was common. "He took me on down the road! ... I stayed with him. That was the first real love of my life," she said, or at least she thought then. "When I met him, he's the one who turned me out. He's the one I prostituted myself for. He pimped me."

Literally. They started traveling to military bases where he would line up johns for her. She gave him all the money, but he took good care of her, providing for all her needs. "They get you. They wine and dine you, and they gradually get you into that kind of a life. They say, 'I'm right here. I'm not going to let him hurt you. He's only going to be there for two minutes.' That's how it goes." And this was a "common" kind of prostitution, she said. She didn't get beat up or involved with drugs.

She got pregnant by someone else. By the time the two of them hit the road to Oklahoma and other states, Knight decided to leave her 6-month-old baby boy, John, with his grandmother in the Addition. She would come visit and brought him out to see her, and sent money back for him. She promised herself that she would return by the time he started school.

Gradually, as she entered her mid-20s still under her pimp's control, she decided to make good on her promise and return to Jackson. She was also tired of the lifestyle and the fact that he kept taking on more girls who she had to train and look after. "I woke up and I said, 'listen, I don't need you. You're full of S. You get out of my life. You come get these hoes because I'm outta here. It's over, baby," she said.

She left that lifestyle behind. But life back in the Addition was about to get even tougher. She got pregnant with her second child, a daughter, when she returned—they didn't use condoms then, she said. She started working at Whitfield, doing laundry, and later started working at St. Dominic's as a housekeeper, determined that her kids would get a good education.

By the late 1980s the neighborhood started going to hell around her. The crack-cocaine epidemic was heating up. "It was a real, big mess what the drugs started," she said.

As her boy John, whom she worshipped, got older, he started hanging out on the streets. The drug trade, and apparently easy money, lured the bright, charming young man because there wasn't anything else to do. By his mid-teens, he was dealing drugs, hanging out in crack houses that "looked like they rotted from the inside out." He became a Vice Lord back in the days when it was part of the national street gang started in Chicago. He was hit by a police car trying to run from the cops. He was shot six times, arrested often and go to prison three times.

"He was so addicted to that lifestyle that he couldn't see the pain he was inflicting," she said or the "brutal" attitude he carried then.

It was a hard time, Knight said, with crack houses popping up all around, cars lining up and down the street to buy the harsh drug.

One day, a friend at work invited her to her house. There Knight smoked crack for the first time. She became badly addicted. She'd go to work during the day, and then come home to Hill Street, in the home she didn't yet own, lock herself in her bedroom and get high. Meantime, she insisted every day that her kids do their homework and stay in school.

She was addicted to crack for two years before entering rehab in 1994. She was gone for 42 days, leaving John, then about 17, to take care of his siblings; by then, she'd had two more sons. "I was living in my mama's house on Hill Street. I had to raise my brothers and sister," John said. He also used the house as a headquarters of sorts for his business. "I had women living in the house, my home boys, everything. But I made sure one of them women ironed my brother's and sister's clothes, and we got them to school."

While she was in the hospital, John took an overdose of pills and spent three days in the hospital.

Knight says she came home clean and with a spiritual awakening. She now understands that she and her son came up in a community that hadn't been trained to expect success. People there were beaten down and couldn't legally vote until the 1960s; her first job was going house-to-house registering people to vote, funded by a group outside the state.

"They were glad to see somebody," she remembers of the first-time voters.

The mother doesn't blame her family or her neighbors for her mistakes. "Growing up in this neighborhood, we were not motivated to want to pursue careers of any kind," she said. "... It was never discussed. The only thing that was discussed when we were growing up was service in the church."

"Our parents did not encourage us to do our homework," she said. Her parents weren't taught to or expected to do that, either, because they were poor and uneducated themselves, working menial jobs in a city with few opportunities.

After rehab, it wasn't easy or solved immediately, but Knight went to work trying to save her kids, even as all three boys would end up in prison (one is still there now). She went back to school at Jackson State and got a social-work degree and helped run a dorm there. She bought her home on Hill Street.

Now, she's the matriarch of the family, with her little Jack Russell terrier named Bobo that likes to bark at all the family members and friends who come in and out of her house now, or her granddaughter as she leaves to buy clothes for career day at school the next day.

Recently, Knight sat in her big chair and shared her story of trying to help her son in his mission, as he stood outside with several of the young men he is trying to steer to a different life and, at one point, came in and planted a big kiss on her as she told her truth. She is cheering for her boy to change the Addition, to interrupt the violence, to build hope, she said.

"God put it in his heart to mentor with these kids," the mother said.

Read about John Knight's efforts to interrupt violence among young people in the Washington Addition.