Wednesday, May 4, 2016

Photo by Imani Khayyam.

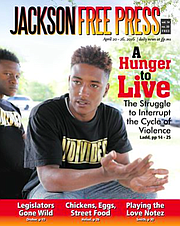

This story is part of the Preventing Violence series.

Oressa Napper-Williams' son Andrell was a victim of gun violence twice. The first time was when he was 16 and a student at Martin Luther King Jr. High School in Harlem. As he walked away from witnessing an altercation, where young people were looking for his cousin, a bullet struck him in the back, but he survived.

Not too long after that incident, Napper-Williams, then a single mother, decided to leave New York City, and move to New Jersey. She still worked at her church six days a week then, in East New York, a Brooklyn community filled with housing projects, police and gun violence. "We still were able to come back and forth (to the city), but I didn't want them to go to school in New York, so that's what moved us to New Jersey," she said in December, sitting in a Brooklyn Greek diner, sharing a plate of feta-covered French fries.

But on Aug. 7, 2006, Andrell was in the city after spending the night with family members. At about 10:35 p.m., the 21-year-old was waiting for his cousin outside a house in Brooklyn when a guy started shooting in front of the building, trying to hit two other men in retaliation for a family member they had buried that morning.

An NYPD detective called Napper-Williams with the news. "Mrs. Napper?" he said. "Your son, Andrell Napper, was killed." He told her about the circumstances, before adding, "I'll give you a call back and let you know if he was innocent or not."

"Excuse me?" Andrell's mother said. "You don't even have to call me back."

'All Blood Is Red'

Since her son's death, Oressa Napper-Williams doubled her last name by marrying a good man and became an advocate against gun violence. She runs her own nonprofit in New York City, Not Another Child, in her son's honor, which provides counseling for survivors of those killed in gun violence.

She is also the NYPD's "Voice of Pain" in its Operation Ceasefire call-ins of young gang members at high risk of gun violence. Working with Deputy Commissioner of Collaborative Policing Susan Herman, Napper-Williams believes in the process strongly. She wants the young men to see the pain of a mother who has lost her baby up close and personal.

After the various law enforcement and clergy talk to the young men, Napper-Williams stands before them. She is model-beautiful and talks like a Sunday preacher in the South with a comedic touch. Each call-in is a little different, but Napper-Williams pours out her heart and soul and pain to the usually black young men in front of her.

Napper-Williams is intimately involved in the Ceasefire process, and she believes in its potential, but she still remembers how the detective treated her. And even now, in her vaunted role inside the NYPD, police still disrespect her, she said, when they don't know that she's part of Herman's team.

Such disrespectful treatment of victims of color, even those who may have been involved with crime, only increases the divide between police and communities of color, she said, lamenting how many other mothers must hear the same thing from cops about their kids. "Their children may have been guilty, and it still does not take away that they were still killed. It doesn't take that away!" she said.

A 'Racialized Gulf'

Operation Ceasefire impresario David Kennedy calls the historic divide between the nation's police departments and neighborhoods of color a "racialized gulf" caused by years of bad, racist policing in those communities.

And the policing wasn't merely offensive, he says. "The things we were doing through criminal justice in the name of protecting these communities were actually causing a lot of these problems," he told me in his John Jay College office in December. "... Arresting all the men and breaking up their family structure damaged the natural fabric of the neighborhood by locking everybody up and churning them repeatedly through jail and prison and parole and probation, treating whole neighborhoods with disrespect."

During New York's stop-and-frisk era, African Americans often called the police the "jump-out boys," because they would screech up in their cars, jump out and stop random black men with no probable cause because of the way they looked, and them frisk them. The vast majority were doing nothing wrong and weren't arrested. They were also overwhelmingly black and Hispanic. "Stopping everybody was one of the reasons that the crime was high," he said.

Kennedy says research now proves that massive sweeps of poor neighborhoods—instead of policing that carefully targets high-risk individuals—actually increases crime in those areas, and makes residents afraid to call the cops.

Residents of a majority-black city like Jackson, with mostly black leadership and police, might shrug at the notion. But not so fast, Kennedy says. "The racial aspect is much, much, much less black-white than it is black-police," he said. It's wrong to think that law enforcement's bias against black citizens is the same "white vs. black racism that the country really, of course, did experience for most of its history."

"Where these issues are presenting themselves now is not really about black and white; it's about especially black communities and police departments," he said. "... What it's really about is the relationship between black Americans and black communities and the legal power of America, and the way that power has been exercised ... and the experience of black neighborhoods at the hands of those legal authorities."

"And that doesn't have to be white folks," he added.

'Implicit Bias Is Just Fact'

Kennedy argues that it's time to face the racist culture of most American police departments when it comes to how they treat who they police. "It's overdue and essential," Kennedy said, for police and other leaders to go to their communities of color and admit that they have not served them well, with sentiments like: "We know now that things that we have done with the best of intentions have made things worse. ... We now understand, for example, that when we lock all of your men up, we make things worse. We have crossed the constitutional lines with stops, searches, other things."

He also challenges cops who believe "implicit bias" isn't a real thing. "Implicit bias is just a fact. It's like gravity; it's just there." For police, he said, "it can produce exactly the same kinds of outcomes that outright racism produces without the person doing it having a racist bone in his body."

David Kennedy is part of the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice, which is calling for police reconciliation work. Read more at jfp.ms/coptrust.