Wednesday, March 22, 2017

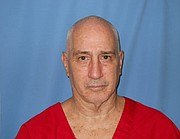

Richard Jordan, then 29, needed money, so he drove to Gulfport, Miss., looking for it back in 1976. There, he called the Gulf National Bank, asked to speak with a loan officer and was directed to Charles Marter. Once he had Marter's name, Mississippi Supreme Court opinions say Jordan ended the call, then looked up Marter's address in a local phone book and went to his house. He entered the home pretending to be an employee of the electric company, then kidnapped Charles' wife, Edwina, who was there alone with her 3-year-old son. The toddler was still sleeping upstairs as Jordan forced Edwina to drive them into a deserted area of the DeSoto National Forest.

What happened next in the woods is disputed in court records, but either way, Jordan shot Edwina in the back of the head. Jordan's defense team claimed that Edwina tried to run away, and Jordan attempted to fire a warning shot and missed. The State of Mississippi argued that Jordan killed Edwina as she kneeled in front of him "execution style." The bullet, court records say, entered her skull at the lower right area of her brain and exited her left eye.

Jordan left her body in the woods and disposed of the murder weapon in the Big Biloxi River. He called Charles Marter, claiming his wife was alive and demanding a ransom of $25,000. Charles was supposed to drop off the money on the side of Highway 49 on a blue jacket that Jordan left there for him.

When Jordan went to collect the money, two officers were waiting to arrest him. He escaped, but police later caught him at a roadblock. He confessed to killing Edwina and told the officers where to find her body. Jordan was first convicted and sentenced to death in 1976, and has been waiting to die for about 40 years due to multiple sentencing trials and shifts in Mississippi's death sentencing law as well as subsequent legal challenges to the use of certain lethal-injection drugs in the state.

The now-70-year-old has been sentenced to death four times as well as had five capital sentencing trials, litigation necessary because Mississippi law keeps changing. At one point, Jordan was sentenced to life in prison without parole—until the court determined that at the time, state law did not permit that sentence based on Jordan's case. Once the Legislature did change state law, Jordan asked for a life in prison sentence, but prosecutors decided to pursue the death penalty again instead.

The State might be able to kill Jordan and others on death row if an effort to change Mississippi's death-penalty law succeeds this legislative session. Still, litigation challenging several components of the state's lethal-injection procedures, including a drug the State plans to use, will likely keep the 46 inmates, by the state's public defender's count, on death row in limbo for the foreseeable future.

Time to 'Change the Language?'

The State of Mississippi is litigating legal challenges to the state's lethal-injection law directly. Mississippi last executed a prisoner in June 2012, Mississippi Department of Corrections records posted online show.

Currently, Mississippi's method of execution is lethal injection with a cocktail of three drugs. State law describes its chosen form of the death penalty this way: "The manner of inflicting the punishment of death shall be by continuous intravenous administration of a lethal quantity of an ultra short-acting barbiturate or other similar drug in combination with a chemical paralytic agent until death is pronounced."

Mississippi has struggled in recent years to comply with this law, largely due to an inability to find those drugs listed in the statute, state officials say. In court records, the State claims it has struggled to obtain an "ultra short-acting barbiturate" or a "similar drug" to use in its place, and it is litigating challenges its proposed use of a drug called midazolam in its place.

In July 2015, the Mississippi Department of Corrections abruptly changed its lethal injection-protocol policies, claiming that it could not acquire pentobarbital, what was supposed to be the first drug in the three-part series needed for executions. MDOC changed its protocol to include alternatives if it could not acquire the drug, including midazolam.

This change spurred the shift in focus in lethal-injection litigation for attorneys challenging the death penalty who argue that midazolam is not a substitute for pentobarbital, arguing among other things, that it's not in the same drug class. Midazolam is in the benzodiazepine drug class, while pentobarbital is in the barbiturate drug class that state law requires.

House Bill 638 would change this policy entirely. The language of the bill calls for "the sequential intravenous administration of a lethal quantity of the following combination of substances: an appropriate anesthetic or sedative, a chemical paralytic agent and potassium chloride, or other similarly effective substance."

Attorney General Jim Hood, the only statewide elected Democrat in Mississippi, has pursued the death penalty even in questionable cases, like that of Michele Byrom. He told reporters in January that the bill, which lawmakers also introduced in the 2016 legislative session before it died, is necessary for executions to resume.

"There's some language in there that says 'a fast-acting barbiturate,' and that's what we've been litigating all this time. ... Well, there are no more barbiturates out there that are fast-acting that are available for executions, so we want to take that out of there," Hood said at a press conference in January about his legislative priorities.

The legislation would also allow alternative methods of executions, including nitrogen hypoxia (death by inhaling lethal gas) and electrocution. Initially, Rep. Robert Foster, R-Hernando, had included firing squads as an alternative in the bill he authored. That version passed the House, but the Senate took the firing squads out.

Foster says lethal injection is the best option, and that the bill is broad enough to enable the state to continue to use the method to kill inmates. The State would only choose other methods like a gas chamber or firing squad if lethal injection is deemed illegal, he said.

"If lethal injection continues to be challenged in the courts, we'll go back and use some methods that have been used for decades," Foster told the Jackson Free Press. "I think firing squad would be just as good as any of them, I mean it gets the job done, and it definitely makes the message clear. It's pretty much foolproof—that's why I would prefer the Senate not (have) taken that out."

Rep. Andy Gipson, R-Braxton, invited conference on the bill, meaning he did not concur with the changes the Senate made to the bill. This means there's still a chance that the option to add firing squad as an alternative back into the bill. He told the Jackson Free Press that he is inclined to keep the legislation alive, but said he had not decided on specifics by press time.

Attorney General Hood seemed optimistic that the State would be able to begin executing inmates again in 2017 during a January press conference. "I think towards the end of the year, probably. I think it's teed up to (where) the courts need to move on (some cases)," Hood told reporters then.

Legal wrangling could stall that hope, however. The lethal-injection litigation saga has continued into the new year with new constitutional claims in federal court against Mississippi's lethal-injection law.

Stopping 'Botched Executions'

Mississippi's lethal-injection litigation nightmares are coming mainly from the MacArthur Justice Center in New Orleans where attorney James Craig, who represents several Mississippi inmates on death row, works. In September 2015, three inmates on death row, including Richard Jordan, filed a federal complaint against the state for violating their rights to due process and "to be free from cruel and unusual punishment" under the U.S. Constitution.

Lawyers amended this complaint just months after the Mississippi Department of Corrections changed its lethal-injection protocol that July to substitute a drug called midazolam as one of the three drugs in the series that creates the lethal injection. Midazolam, Craig and other attorneys allege, could create a substantial risk of harm to those on death row.

The State denies that midazolam creates a risk and but does admit in court documents that "MDOC intends to use midazolam as the first drug in Plaintiffs' executions and that midazolam is classified as a benzodiazepine."

The legal challenge against midazolam relies on the question of whether or not it is really "a similar drug" to the increasingly hard-to-get barbiturates, which Mississippi law currently allows. Midazolam is a sedative considered a "benzodiazepine" drug class—not a "barbiturate." Lawyers and advocates against the death penalty—and against the use of midazolam—argue that midazolam is not a true anesthetic, therefore not guaranteeing that it will render a person unconscious, which is its purpose.

Oklahoma state employees used midazolam in the botched execution of Oklahoma inmate Clayton Lockett in 2014; the procedure took 40 minutes before he finally died of a heart attack.

Arizona and Ohio officials also used midazolam in two executions where prisoners "showed visible signs of pain before dying," as Newsweek reported.

The U.S. Supreme Court did not deem midazolam unconstitutional in a case from Oklahoma, leaving the potential for future litigation about the drug open, since its ruling only applied to the evidence that Oklahoma inmates presented. In its 2015 Glossip v. Gross ruling, Justice Samuel Alito wrote that the prisoners failed to identify known and available alternative methods of executions that "entail(s) a lesser risk of pain." The 5-4 decision on June 29, 2015, came down just a month before MDOC announced that it would change its death-penalty protocols to include midazolam.

If House Bill 638 becomes law, this legal question will be moot—because the new wording broadens the language, allowing the state to legally use midazolam. Attorney General Hood sent a statement to the Jackson Free Press about the current bill to change the state's death-penalty law.

"Because we cannot obtain the first drug in the three-drug protocol and now are experiencing difficulty obtaining the second and third drugs, we have requested a change in the language on the types of drugs to be utilized, as well as alternative means," the statement said.

Advocates oppose the use of midazolam as well as the broad language in the bill, however. The ACLU of Mississippi, which opposes the death penalty generally, also opposes House Bill 638. Blake Feldman, one of the advocacy coordinators there, said midazolam is to blame for several botched executions—and that it is disturbing that state officials would want to use a drug that has been the root of problems elsewhere.

"We can't ignore that what this bill does is it very seriously increases the chances of a botched execution. ... The death penalty is a gross injustice, but a botched execution by the State paid for with tax dollars in our name is as bad as you can get," Feldman told the Jackson Free Press.

While Richard Jordan, Ricky Chase and Thomas Loden's midazolam complaint will be moot if House Bill 638 passes, the three death-row inmates will continue to challenge the use of a three-drug lethal-injection procedure as unconstitutional.

That is, the state's legal problems over the death penalty are far from over.

Likely 'More Delay'

Craig and lawyers representing Jordan, Chase and Loden still allege that Mississippi's three-drug protocol is unconstitutional. Craig said he was surprised that Mississippi's proposed legislation does not change its death penalty more drastically. States embracing the death penalty use lethal injection, but the majority that actually executed prisoners in 2016 used a single-drug lethal injection, often made up of a high dose of pentobarbital. That is the kind of drug that Mississippi claims it cannot get, saying it needs to use midazolam in its place.

If House Bill 638 becomes law, Craig said he expects to amend Jordan, Chase and Loden's complaint in federal court accordingly. Discovery materials in the case are due in September 2017, meaning the trial will likely not be held until 2018, but amending that complaint could delay that litigation even longer and keep the three inmates alive until it is resolved. Craig said he could amend the complaint to add that nitrogen hypoxia and electrocution, both listed as alternative methods of execution in the proposed legislation, also violate his clients' constitutional right to no cruel or unusual punishment.

"I think we would end up bringing a different set of claims in Judge (Henry) Wingate's court. Assuming he doesn't immediately ban it, that's another almost year, two years delay to what's already going on right now," Craig said.

Judge Wingate himself was temporarily blocked from handling new cases last week after Chief U.S. District Judge Louis Guirola directed court clerks to assign any new civil cases to three semi-retired judges instead of Wingate, the Associated Press reported. Wingate has a backlog of pending cases that need to be ruled on before he can take on any new cases.

Texas, Georgia and Missouri executed prisoners in 2016 using one-drug lethal injections that Craig says are more humane than the three-drug cocktail in Mississippi. He added that around 90 percent of his legal claims against Mississippi's lethal injection procedure would be moot if the State moved to using a single-drug pentobarbital lethal injection.

State officials, including the attorney general, claim they have had trouble getting their hands on pentobarbital, however, but a recent public-records request by the MacArthur Center seems to challenge this.

MDOC released its lethal-injection drug inventory forms showing the state is in possession of midazolam—but does not have any other drugs necessary for the three-drug injection.

Additionally, MDOC said that no records exist showing "any and all efforts or attempts made by MDOC to acquire" any such drugs. That is, it is unclear how hard the State is working to get the additional drugs in order to proceed with executions.

The 'Alternative Methods'

Mississippi would be the second state in the country to enact a method called nitrogen hypoxia if House Bill 638 becomes law. Rep. Foster, aware that the lethal-injection litigation is stalling the death penalty, added several other measures the State could carry out in lieu of the lethal injection. Originally his bill added nitrogen hypoxia (lethal gas), firing squad and electrocution in that order as alternatives to lethal injection—if that method is deemed unconstitutional.

Most states with the death penalty use lethal injection to execute people. Oklahoma, after all its negative lethal-injection headlines seems to be moving forward with a new method: nitrogen gas.

In 2015, Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin signed a bill to allow the state to use the method to execute its prisoners on death row, and last September, the attorney general there suggested that the state needs to develop a protocol for the new method, the Tulsa World reported.

The only hang-up for nitrogen hypoxia is that there are no reports of it ever being used to legally execute a human, the Associated Press reported in 2015. In May 2016, a grand jury in Oklahoma issued a report about what went wrong in another botched lethal-injection execution, and in that report, suggested that nitrogen gas could be a better alternative for the state to use, The Oklahoman reported.

Robert Dunham with the Death Penalty Information Center, which tracks death penalties and executions nationwide, confirmed that Mississippi would be the second state to add nitrogen hypoxia to state law. Dunham said no scientific evidence supports the method because it's never been done on humans before. Gas chambers that were previously used for the death penalty used different gas, usually cyanide, Dunham said. Hypoxia is sometimes used to put animals to death, but the American Veterinary Association guidelines say it is not appropriate for all species of mammals.

American Veterinary Medical Association developed guidelines in 2013 that describe hypoxia. "Some animals may exhibit motor activity or convulsions following loss of consciousness due to hypoxia; however, this is reflex activity and is not consciously perceived by the animal," it said. "In addition, methods based on hypoxia will not be appropriate for species that are tolerant of prolonged periods of hypoxemia."

Nitrogen hypoxia would most likely be subject to Eighth Amendment challenges for cruel and unusual punishment, Dunham said, as would electrocution. Tennessee lawmakers added the electric chair in 2014 as a back-up execution method, but courts there chose not to rule on if it is cruel or unusual punishment until the lethal injection method there is deemed unconstitutional. Mississippi switched from using an electric chair to a gas chamber to execute inmates on death row in the 1950s through the 1980s to kill 35 death-row inmates. In 1984, the Legislature first added lethal injection as an option, and then by 1998 removed the gas provision from state law.

'Let God Sort It Out'

While some lawmakers do not believe in the death penalty, based on how House and Senate members voted on the bill this session, most agree that the state needs to follow its own laws. Hood said in January that it is his job to enforce the law, and if the law is going to be changed, the Legislature will need to do that.

Based on the support for his firing-squad amendments in 2016 and this year, Rep. Foster says the House seems to be overwhelming for the death penalty in the state. House members passed his bill by a vote of 74-44 this session, and the Senate passed its amended version (with no firing squad) by a vote of 38-13.

Foster said he is in favor of executing those who commit the most egregious crimes with undeniable evidence.

"When people do just horrible acts of evil, not crimes of passion, but just terrible acts of evil, then I do think (there should be a death penalty). It does save us money if we do it earlier than drag it out for 50 years, but it's not so much about the financial side," he told the Jackson Free Press.

"It just sets a precedent. I don't think it's right for them to be able to live their life out in jail and get three meals and have access to workout equipment and access to medical care potentially better than we're giving to some of our veterans in some cases, for the rest of their lives. ... I think we need to send them on for their final judgment at that point and let God sort it out."

Dunham said national public opinion is not on the Mississippi Legislature's side when it comes to alternative methods of execution. Public support for lethal injection as a method of execution is waning, but a majority still favors it, however, over the alternatives. A YouGov poll from 2015 shows that a majority of those polled about methods of execution including hanging, gas chambers, firing squads and the electric chair believe that they are all cruel and unusual. Dunham said Mississippians' support of those alternatives could lead national public opinion—and business development in the state—to suffer as a result.

"Even if the public in Mississippi thought that (alternatives) were OK, it's bad for business because it creates an image of the state as being barbaric," he said.

"That is not a good atmosphere for economic development."

Mississippi is one of 31 states that have a death penalty. The number of state executions nationally has declined in recent years. The Death Penalty Information Center reported 28 executions country-wide in 2015 and 20 in 2016. Other states use different lethal-injection protocols, some using single-drug injections, while others use three-drug injections like Mississippi. Dunham said House Bill 638 signals Mississippi is in line with national trends with states dealing with how to execute its prisoners by legal injection when drugs they want are no longer available or just difficult to obtain.

"Some states are looking to change the chemicals that they use, but not the process," Dunham told the Jackson Free Press. "Others are looking to move from multiple to single drugs, and others are looking to back-up methods of execution."

An Exhausting Legal Process

A person sentenced to the death penalty technically gets a chance at one federal and one state appeal, but several inmates in the state were able to file additional petitions after Mississippi created the Office of Capital Post Conviction Counsel that did not, in some cases, raise the proper claims, leading to more litigation.

Andre de Gruy, the state public defender, said only about two of the 46 inmates on death row have exhausted their appeals outside of a lethal-injection claim, meaning the rest of inmates on death row are challenging their death sentences for other reasons.

"The vast majority of cases are not being held up because of this," de Gruy said.

Craig filed a separate post-conviction relief petition on Richard Jordan's behalf last summer. Because Jordan has had to wait four decades and is now 70, executing him should be considered "cruel and unusual punishment," the petition argues.

At one point, Jordan was eligible for an agreement to a sentence of life in prison without parole, but the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled that the "life" sentence was unlawful under law at the time of his crime. Craig argues that Jordan was at a disadvantage in court even in 1998 during his fifth sentencing trial.

"Jordan had to confront a jury that would, because of the deaths of (his) family members in the intervening years ... never experience the emotional force of testimony of those who loved him dearly," Jordan's latest petition to the Mississippi Supreme Court says. "In short, Jordan was denied the very type of evidence that routinely spells the difference between life and death in capital trials in Mississippi."

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected] and follow her at @arielle_amara for breaking news.