Wednesday, November 15, 2017

An African American first grader clutched his mother’s hand as he arrived for the first day of school at previously all-white Davis Elementary School in Jackson on Sept. 14, 1964. Black students could voluntarily integrate white schools back then, but local public schools would not fully integrate until 1970. (AP Photo)

It was a cold winter day in 1969, but Brenda Walker was not thinking about the weather when she put her coat in her locker. After all, Central High School in the middle of downtown Jackson had radiators to heat the classrooms.

Central was traditionally an all-white high school, but Walker was one of a handful of black students who opted to attend Central despite little encouragement from family or friends. Black students were allowed to voluntarily integrate white schools in Jackson after Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

When Walker walked into her biology class, she noticed all the students sitting on the side of the room nearest the door—but that was not unusual. She was usually the sole black student in her classes, and she was accustomed to her white counterparts never sitting in the same row as her due to her race. This day, however, she noticed that her classmates wore coats and hats.

As she took her place in a row of her own next to the windows, she realized the large glass panes were wide open. She had walked into a trap, and she was stuck.

"Oh God, they planned this," she thought to herself, realizing that she could not just get up to go to her locker for her coat and still get back to class on time.

The biology teacher, who Walker remembers was not white or black but cannot recall his name, came in and began teaching. Walker, the only black student in the class, was shivering. The white students, bundled in their coats and hats, were warm and smug. The biology teacher walked over to the window and began closing them one-by-one as he taught. Soon, the class was stifling hot, and the white students began to remove their gear.

"No, everybody that has a coat or a hat on leave them on until the next period," the teacher told the class.

Walker remembers that day with gratitude because her biology teacher at least in an indirect way acknowledged the discrimination she had experienced. She recalls her choral music teacher never saying a corrective word to her white classmates, who always managed to make sure that the books she placed neatly on a chair during practice ended up on the floor.

Jackson's public schools, like the majority in the state, remained solidly separate and unequal in the 1950s and 1960s despite the ruling in the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision in 1954, which struck down school segregation by race.

One look inside Central High School, and it was clear that Mississippi had no intention of integrating its schools. Walker knew this when she decided to enroll. Her parents, a cement finisher and a seamstress, worked hard to send her to an all-black Catholic school, Christ the King, for all of elementary and part of middle school. In middle school, she had to go to Blackburn, however, which was a shock for the somewhat sheltered, youngest child in her family. Blackburn was all-black.

For high school, Walker had the option to attend a white school, technically speaking. By then, students had the legal choice to go to white schools, but few black families were willing to send their children to all-white, potentially hostile schools.

Walker was determined, and based on her life experiences up to that point, she did not see any reason white classmates should treat her differently. All of the white people she had encountered had not treated her any differently on account of her skin color. And she was determined to show she could succeed in an integrated school. "I read an article, and I can't remember who it was by, but it said if you put a black student and a white student together, the black student couldn't keep up," she recalls.

That motivated the determined teen to tell her parents she wanted to attend Central. Once she enrolled, her father would pick her up every day right when school ended to make sure she did not linger in hallways or on the school grounds because he believed it was potentially dangerous for her. Walker says she found a group of white girls who befriended her and walked her to class every day.

The posse ended up protecting Walker, she believes, because no one would harass her or say anything to her after that.

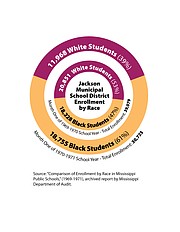

In Jackson's public schools, Walker was an anomaly at the time. The majority of students stayed in schools separated by race. By 1969, Walker's junior year, more than 39,000 black and white students were enrolled in the school district in Jackson, mostly attending separate but decidedly unequal schools.

Disseminating 'Racial Facts'

While much of the country grappled with how to integrate schools in light of the 1954 Brown decision, Mississippi doubled down on keeping public schools separate and unequal. Instead of combining student bodies or distributing students evenly across public schools in Jackson, school leaders here opted to raise more funds to give to the black schools—even though still less than the predominantly white schools enjoyed.

The Jackson Municipal Separate School District was separated by race into all-black and predominantly white schools. Brinkley, Jim Hill and Lanier High Schools served only black students, while Murrah, Central, Provine and Wingfield served predominantly white students. Central had the most black students voluntarily attending, with 84 enrolled in 1969, while Wingfield had no black students attending the fall before court-ordered integration, an archived report from the state auditor's office shows.

Historic public-school enrollment records from the Mississippi Department of Education show that, pre-integration, black schools in Jackson were overcrowded in comparison to the white schools. Charles Bolton notes in his heavily researched book, "The Hardest Deal of All," that in 1968, the district served 10,000 black students and 11,000 white elementary-aged students—but had 26 white elementary schools and only 13 black elementary schools.

Soon after the 1954 Brown decision—a day many white Mississippians called "Black Monday"—a former Mississippi State University football star, Robert "Tut" Patterson," started the Citizens' Council in Indianola, Miss., to push back on integration. The white-supremacist organization quickly attracted a strong membership of business owners and leaders from around the state, including Jackson. It fought integration, through economic boycotts and intimidation of black and white people who might go along with it, and eventually boasted more than 80,000 members in chapters across the South.

In 1956, the Legislature appropriated funds to the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, a state spy agency that investigated "suspicious" white and black citizens for any possible efforts at integration, including a white business owner allowing a black person to use their public restroom. The Sovereignty Commission also helped fund the Citizens' Council; both were supported by an extremely racist media network in the state, led then by The Clarion-Ledger and Jackson Daily News in the capital city.

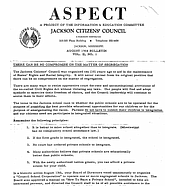

Early in its tenure in the 1950s, the Citizens Council used intimidation to keep citizens of all races from acting on their new federal right to integrate public schools. But by the mid-1960s, with more schools in surrounding states allowing integration, Citizens' Council leaders grew increasingly worried about integration actually occurring in the state's public schools, and began to plan accordingly. The Council disseminated a swath of public documents with "racial facts" and newsletters to Jackson parents warning them of the rising tide of integration. "It is better to miss school altogether than to integrate. (Mississippi has no compulsory [sic] attendance law)," a bulletin released by the Jackson's Citizens' Council in August 1964 said.

In a special session in 1964, the all-white Mississippi Legislature passed the tuition-grant law, allowing public funds to be used on private, non-sectarian schools. This allowed white people to send their children to "council schools" using taxpayer dollars. In the capital city, the Citizens' Council opened its first school in the fall of 1964.

The all-white Legislature implemented a "freedom of choice" program, enabling students to choose which school they wanted to attend and enabling some black students to attend white schools, if they dared.

Bolton describes "freedom of choice" as a delaying tactic for white officials in Mississippi that worked quite effectively in courts until almost the end of the decade.

"Freedom-of-choice desegregation was viewed by Mississippi segregationists as a way to bend their devotion to racial segregation just enough to satisfy federal laws and black demands while preserving as much of their dual school system as possible," Bolton wrote in his book.

Thus, for more than a decade after integration was federal law, Mississippi successfully kept most white and black children separate through a network of laws.

The Council schools, listed in archived non-public school records as "C 2, C 3, etc.," were mainly named after the streets they were built on. Council Manhattan was on Manhattan Road, for example. The Citizens' Council opened five schools in Jackson, records show. By 1979, the Council schools are listed as "academies" in archived data from the Mississippi Research and Development Center. In 1979, three "segregation academies" remained in Jackson: Manhattan Academy, Magnolia Academy and McCluer Academy (spelled McCleur in archived records). The academies faded out in the mid-1980s, some turning into or taken over by Christian academies. Woodland Hills Baptist Academy moved to the Manhattan Road address where the Council school previously sat. Gov. Phil Bryant's south Jackson alma mater, Council McCluer, became Hillcrest Academy in 1985, for instance.

Enter 'Scientific Racism'

After the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964—in response to racial violence including the murder of three civil-rights workers in Neshoba County—school districts were required to file desegregation plans. Jackson's white district leaders refused, and several black parents filed a lawsuit. They alleged that the Jackson Municipal Separate School District was "a compulsory biracial school system," which violated due-process rights of the black parents and students.

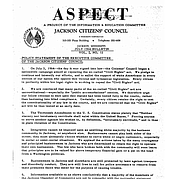

The school district mounted a defense, based largely on faulty science, that argued that the natural differences between black and white children were enough reason to keep the two races separate. In the Citizens Informer newspaper, The Citizen magazine and openly at public appearances, the head of the Citizens Councils of America, William J. "Bill" Simmons of Jackson pushed the myths of "scientific racism" that argued that black children were genetically inferior and, thus, could not learn as well as white kids and were more prone to crime.

"We have segregation because there are distinct differences between the white and black races that make it advisable. I am not talking about total inferiority or superiority—I am talking about differences," Simmons said at a speech he made at Notre Dame University in Indiana in 1963.

The federal U.S. District Court in the 1960s agreed with the scientific-racism "evidence" that Simmons and others pushed, saying the judges in the Brown case may have erred based on "evidence" presented at the Darrell Kenyatta Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District case.

"Defendants first presented evidence pertaining to the scholastic achievement and mental ability (I.Q.) of the members of the white and Negro races, as reflected by the records maintained by the Jackson Municipal Separate School District, and pertaining to such pupils within such District. These records disclose that there is a wide discrepancy between the scholastic achievement and the mental ability, as shown by recognized tests used nationally," U.S. District Judge Sidney Mize wrote.

"These records disclosed a noticeable and substantial difference in the scholastic achievement of the members of the Negro and white races and a difference in the scores attained on the nationally recognized mental ability tests, with the white pupils consistently scoring above the national average and the Negro pupils consistently scoring below the national average. The disparity between the members of the two races as reflected by the mental ability tests became more pronounced as the age of the pupils increased."

After the Evers ruling, black parents continued to fight segregation in the courts. One of the federal lawsuits, Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, ultimately produced the desegregation plan for the state's largest district in 1970.

Outside the courtroom, Jackson's local school leaders attempted to keep the peace with their black counterparts in local public schools during the Civil Rights Movement. Black schools did see an influx of money in the 1960s, but it still did not equal the funding in white schools.

Jackson spent $149 on each white student in 1962 and $106 per black student, data from an unpublished Mississippi Department of Education document Bolton uses in his book shows. School funding decisions became tense, as black Jacksonians began demanding their rights to more taxpayer funds for their schools. William Dalehite, an educator and administrator in the district at the time, notes in his book, "A History of Jackson Public Schools," that the NAACP helped successfully block the district from making planned classroom additions to white schools in the 1960s.

In 1969, a bond issue to make Lanier High School, which was black, also a junior high school and to convert Callaway, a white school, into a senior high school failed. Dalehite notes this was the first time a bond issue failed. White and black taxpayers in Jackson suddenly were not willing to increase funding for their public schools in the face of the uncertainty that came with impending integration.

Culture Shocks

Fifteen years after Brown v. Board, the patience of the U.S. Supreme Court had worn out, and it lowered the boom on resistant states in the Alexander v. Holmes case—which included dozens of Mississippi school districts resisting integration—saying on Oct. 29, 1969, to integrate now.

"Continued operation of racially segregated schools under the standard of 'all deliberate speed' is no longer constitutionally permissible. School districts must immediately terminate dual school systems based on race and operate only unitary school systems," the Supreme Court said.

The ruling forced the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to mandate school-district leaders involved in the Singleton v. Jackson case to complete an integration plan immediately. This meant an extended 1969-70 winter break for students in Jackson as district leaders submitted, then re-submitted their integration plans to the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Superintendent John S. Martin, staff and attorneys met with federal officials in Atlanta over the break, Dalehite writes, and hammered out the re-districting plan.

"The superintendent and three staff members flew to Atlanta on Dec. 21 for a two-day meeting. Armloads of cumbersome maps and much pupil data were carried to the borrowed work space. A plan acceptable to HEW representatives was hammered out within hours of the Christmas Eve rush out of Atlanta," Dalehite wrote.

The district closed schools for two weeks near the end of January to implement the plans, but students at the time remember the initial desegregation plans in spring 1970 as mainly a mix-up of teachers with a few students switching schools. The noticeable integration plan kicked in when students were districted for different schools come fall 1970.

Robert Gibbs' world was completely segregated from the white world in Jackson. He attended all-black schools. Now a prominent trial attorney and former circuit judge in Jackson, Gibbs lived in the Virden Addition and attended an all-black church. He had no white friends or any real contact with white people, except the two white students who came to Brinkley in spring 1970 after the integration order took effect. But that fall, Gibbs was forced to leave the familial warmth of Brinkley, an all-black high school known for its culture. He lived four houses away from being slated to attend Callaway, which is where his best friends would go. Gibbs, however, was slotted into the Murrah zone.

Gibbs' school experience—from Brinkley to Murrah—was a huge shift for the 11th grader. He had played drums in the band at Brinkley and recalls the upbeat, soulful music with majorettes who danced to almost every song with swag.

"My band at Brinkley went from playing songs by James Brown to doing the 'Good Ship Lollipop,'" Gibbs told the Jackson Free Press. "You talk about a culture shock, that was a culture shock."

Murrah also meant that Gibbs was now on his own in the classroom—not that it mattered. Gibbs says he got good grades at both Brinkley and Murrah, but the attention he got from teachers changed.

"The teachers that we had at Brinkley were nurturing. They wanted to make sure we did well, and if we didn't do well, they would pick up the phone and call our parents," Gibbs recalled. "Then when we integrated into Murrah, you didn't have that kind of nurturing, you know, it was like if you get, you get it and if you don't get it, that's tough. If we didn't do well, you didn't have to worry about nobody calling your home or coming to talk to you parents. You just got a bad grade and that was it."

Angering Bill Simmons

Alan Huffman, a local writer and researcher who was attending Chastain as a ninth grader in 1969-70, remembers disarray after winter break. He said while things did not get violent, it was more just disorganization and confusion at the administrative level after court-ordered integration.

From 1970 to 1971, Dalehite notes in his book that 56 teachers left the Jackson school district.

Huffman asked his parents to attend Council Manhattan because that was where his best friend at the time was going. Huffman attended the Citizens' Council school on 5055 Manhattan Road for his 10th-grade year. Huffman said as a 15-year-old white kid, air conditioning and the ability to drink Coke in a Council school was enough to convince him to go. However, he did not last long there.

Huffman found Council Manhattan in the same disarray as Chastain, he recalled. He had two study-hour periods back-to-back with no instruction, and he began reading copies of The Citizen, a magazine Simmons and the Citizens' Council produced, that sat in the school's library.

"It was all about how black people are genetically inferior to white people and that their mental capacities were less, and all that kind of stuff ... but it was so shocking to me," Huffman recalls.

Huffman knew only a few black people growing up, he said. His parents were reasonable people, he said, but not so liberal that they were interested in going to newly integrated restaurants. He has fond memories of Helen, the family's housekeeper, but never learned her last name. Huffman said his parents never used her surname that he remembers. Reading the Citizen magazine, however, Huffman realized the writings seemed to imply Helen was inferior, too.

"They were saying Helen was biologically and mentally inferior to me, and it just bothered me so I started writing letters...rebutting all of these articles," he said.

Huffman's letters made their way to William J. Simmons, who called Huffman's father in for a meeting and told him that Alan needed psychiatric help. Huffman's father asked to see one of his letters, and after reading it, told Simmons, "I pretty much agree with everything he said."

The confrontation with Simmons meant the end of Council school for Huffman, who was excited to transfer to Murrah High School. By fall 1970, Murrah still had a majority of white students, but 44 percent of the student body was black, archived data from the state auditor's office show.

White Rush to Academies

Integration in Jackson meant students could only attend certain schools within the geographic vicinity of their houses. For Dana Larkin, this meant attending Brinkley for 10th grade, after school district officials converted the formerly all-black high school into a 10th-grade attendance center. Larkin was at Bailey, on the corner of State Street and Woodrow Wilson, when the integration court order came down the spring before. Larkin's mother, however, decided public schools were out of the question after she attended a meeting at Brinkley.

"The story goes, my mother went to orientation at Brinkley for me. ... She said that they really scared her and said that the dads should drive them, and it's a bad neighborhood, 'be careful.' So she said that she left there, took her car, and went to Jackson Prep and registered me, and that was that," Larkin says.

Larkin was unhappy at the then-all-white Jackson Prep, which opened its doors in August 1970, because all her friends from the synagogue were in public schools. During her junior year, Larkin lobbied to go to Murrah, which she was slated to attend as her family lived in Eastover. They conceded, and Larkin graduated in 1973.

The private Jackson Academy had opened back in 1959, but the opening of Jackson Prep, Woodland Hills Baptist Academy and two Council schools coincided with court-ordered integration, nonpublic school records show. The school names are all handwritten into the back of the 1969-1970 nonpublic school enrollment records stored in archives. The schools began recording enrollment numbers during fall 1970, when they opened their doors to white students. Jackson Prep's enrollment grew in those first years from 652 students in the fall of 1970 to 968 students the following school year, archived state department of education records show. The other private schools, including Jackson Academy and Woodland Hills, saw a bump in enrollment after court-ordered integration too.

"Some of Jackson's wealthiest citizens established Jackson Preparatory School, which had ample resources and soon developed into a top-notch school, although it was only available to those who could afford the tuition," Bolton wrote in his book. Prep today is still majority white, but recruits black students and teachers.

Private-school enrollment shot up overnight after forced integration. The Citizens' Council increased to five schools in Hinds County, serving more than 5,000 students by the 1972-1973 school year.

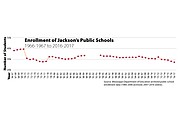

Huffman and Larkin are two of thousands of white students who fled Jackson's public schools in the face of integration immediately, but both returned to graduate from public schools. The majority of white students who left would never return or bring future generations back, at least to date. In 1969, 39,205 students attended public school in Jackson, and the very next year, enrollment dropped to 30,713 students, historic enrollment records show. Nearly 9,000 white students pulled out almost immediately after the Supreme Court decision, an auditor's report shows.

While Jackson's public-school system would swell to more than 33,000 students in the early 1990s, the district's population has not reached pre-integration levels since 1970. The district's white-student numbers continued to decrease every school year following court-ordered integration, based on anecdotal and census data.

Dalehite estimates that in the three years after integration, more than 11,000 whites fled the district, mostly for private schools where black students were then not welcome nor could afford the tuition.

Both St. Andrew's Episcopal School and Jackson Academy began adding grade levels starting in 1971, nonpublic school enrollment records show. Eventually, both schools grew their student-body populations to include high school-aged students—and still serve those grade levels today, with majority-white student populations. Like Jackson Prep, St. Andrew's and Jackson Academy works to recruit and maintain diverse student bodies today.

'Constant Conflicts'

As white families fled to academies and private schools, many black families were forced into new schools or feeder patterns. While the black public schools by then were mostly overcrowded, the black community made do with them, and many students lamented seeing the traditions of the schools dissipate with integration.

Under the desegregation plan, Brenda Walker was forced to attend Provine High School in her neighborhood in west Jackson when the court order took full effect in fall 1970. She could not continue attending Central downtown. Walker was entering her senior year at previously majority-white Provine. "I don't remember so much hostility towards me. I think it was a mass (opinion) thing. Here were these students, we're coming in their school and stuff like that, so it was just conflicts at the school in a big way," Walker said. "I don't really remember anyone saying or doing anything (drastic) ... but just that it was constant conflicts in the school. We would end up leaving school early almost every day."

With so little productivity in a school day, Walker asked to transfer to Lanier High School, which had a 99-percent black population even after integration. Walker participated in a work program at the district's film library, so she only spent half-days on-campus then. Still, when she graduated in 1971, students selected her as class representative to speak at graduation.

"I really felt like what I went through—all that stuff—was to get to that point," she says. "I felt appreciated."

Gibbs said he and his black classmates stunned his Murrah teachers. "They were surprised at how smart and how bright and how advanced we were," he said. "I know most of the people I hung out with, we did extremely well academically at Murrah. I think it really shocked some of the (white) teachers because I do not think they expected we would perform at a level as the students who were already there."

Gibbs, who went on to Tougaloo College and later law school at the University of Mississippi, says he believes his education at both Brinkley and Murrah got him to where he is today. He does not believe that the courses at Murrah got more academically challenging than the ones he had at Brinkley, and his grades stayed constantly solid throughout his high school education.

Generally, black students in the district had to do the hard work of integration, leaving homogenous schools and integrating white ones. Still, Gibbs said he understands why black students had to integrate. As a son of two parents who fought for equal rights in the Civil Rights Movement, Gibbs said his parents were proud of the fact that he, and later his siblings, were able to attend integrated schools.

"I understand why we had to integrate into the white school because I don't think they could have integrated into a black school because if they had to come into the culture that we had, I don't think they could have adapted as well," Gibbs said of white kids.

Huffman and two of his white classmates co-edited a book called "Lines Were Drawn" about the Murrah class of 1973. While writing the book, he realized through interviews with his black classmates what a sacrifice integration was for the black community in Jackson.

"We thought, as white people, that integration was all about us. It never occurred to us that it was about black people," Huffman said. "It was about us needing to let black people go to our schools. That's how we saw it, which goes back to privilege. Realizing that it was just as challenging to them was eye-opening."

Even in an integrated school system, interactions and life could be awkward as black and white teens mingled for the first time, experiencing and learning from their classmates in ways they never had before. Jackson was segregated in most public spaces prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and for a few years afterward. In a way, black and white students brought integration to their households with birthday parties and the social scene. Larkin remembers inviting several of her friends from Murrah to her pool at home.

"My parents ... it's hard to admit but they were definitely prejudiced," Larkin said. "One of the rebellious things I did is we had a swimming pool in our backyard, and my senior year, I invited my African American friends to come swimming because I knew it would push every button my mother had, and it did. It was a scene—she didn't do it in front of them—but it makes me feel guilty because I used them to ... rebel against my mom and my dad."

As several of Huffman's Murrah classmates echo in "Lines Were Drawn," those first graduating classes in the early 1970s in Jackson experienced a special situation.

"We were very, very fortunate. It (Integration) opened our eyes to so many things," Huffman said. "... It made us all better people, and now when you talk to your classmates, they recognize that."

Re-segregation Sets In

The Mississippi Department of Education began publishing student enrollment data by race in the early 1990s, but anecdotal evidence as well as national trends show that integration, while it lasted, peaked in the 1980s. City and county census, school-district and private-school population numbers suggest that white flight set in immediately in 1970 and continued throughout the decades following, with white families fleeing both the public schools and previously white neighborhoods such as neighborhoods around Westland Plaza and Metrocenter in west Jackson and south Jackson.

Some groups, like Mississippians for Public Education—a group of mainly white women fighting for better, integrated schools—worked to keep white families in public schools and fought for the funding and resources needed throughout the district in the 1970s. Parents for Public Schools picked up their work in 1989, attempting to convince middle-class white and black families to consider staying in Jackson Public Schools and continue living and investing in the city to keep it from decaying and failing from flight and disinvestment.

Susan Womack led PPS of Jackson from 2000 to 2012, where Larkin also worked. Womack would give school tours and talk to families about options in Jackson's public schools available to them, showing them the benefits of public schools.

"We continued to see people just leave in droves because they weren't happy for one reason or another. It's too easy for families who have needs to give up and go somewhere else if they don't like what they're getting," Womack said. "(Families gave mainly) reasons that could have been translated to 'I'm not comfortable in this environment once the population became majority-black,' and I fully believe that's what landed us where we are today."

When the Mississippi Department of Education first published race data for school districts in 1994, the district was already a majority-black district by a large margin: By then, 27,868 of the district's 32,731 students were black or 85 percent of the student body, historic MDE enrollment records from the Department of Archives and History show.

Before the court order in fall 1969, black students made up 47 percent of the total student body, archived race data from the state auditor shows, but by fall 1970, 61 percent of the student body was black. Private-school enrollment skyrocketed as a result, and as the decades ticked by, Jackson schools steadily lost white students—and total enrollment numbers.

Womack, who is now the associate vice president for developmental operations at Millsaps College, saw many white families who sent their children to private schools who had left public schools themselves as children after integration.

"Over time, families became so accustomed to going to private schools that it became a generational thing. You know, Mississippi is such a legacy place, so that if my parents went to Jackson Prep, St. Andrew's or Jackson Academy, that's where I'm going, and now we have two generations of people who have never been inside public schools," she said.

Families who left the city altogether likely account for the growth in public-school populations in Madison and predominantly Rankin County. Today, however, despite 20 percent of Jackson's population being white, white students make up less than 5 percent of the student body at JPS, indicating that they are enrolled in private institutions or home-schooled instead.

'It's What You Model'

Brenda Walker adopted an infant daughter in 1991. Initially, Walker thought about sending her daughter to Christ the King but when she got laid off from her job, she sent her to JPS, unsure of being able to pay for private school. Her daughter, Alexis, grew up in the predominantly black Jackson Public Schools, attending Pecan Park, Hardy Middle School and then participating in the IB Program at Jim Hill High School. Walker said Pecan Park felt like a small, private school, noting how much she appreciated the principals Alexis had there during that time.

Alexis had almost the opposite experience as her mother. Brenda estimates there were about four to five white kids in Hardy Middle School, but said her daughter was involved in enough programs and clubs outside school to expose Alexis to kids who do not look like her, like Girl Scouts.

"The reason why I love integration is because that's the world," Walker says. "(In segregated schools) you really, you know, you're leaving your kids to not really seeing what it's going to be like when you get out and get a job or go to college or you know, just do these things, because it's just not a true look of what's out there."

Larkin and her husband, Jonathan, sent their two daughters to JPS schools all the way through high school with them later attending Brown University and George Washington University. She says public education and fighting for her kids to have the best education possible is connected to the practice of her faith. One of the tenets of Judaism, tikkun olam, means to "repair the world." Larkin said this belief drives a lot of her justice work currently but also influenced her parenting.

"(It's) what you model, not what you teach your kids or preach to your kids. It's what you model, so they saw me fighting for public schools and volunteering on the PTA and at the temple," she said.

Womack and her husband have one son, whom they sent to JPS, while she was still working at PPSJ. She said when they enrolled her son in Casey Elementary, his classes were much more integrated then when he later graduated from Murrah. He was one of no more than 20 white students to walk across the stage in 2014.

"People would say, 'where does your son go to school?' I would say Casey Elementary in JPS, and they would say 'Oh,' and walk away," Womack said. "It's really disturbing that the (white) community and the public have abandoned public schools so drastically in communities like Jackson, and in other communities where the majority population is black."

Why Integration Matters

The story of the re-segregation of Jackson’s public schools is not unique to Jackson or Mississippi. School districts across the country’s urban centers are becoming increasingly segregated along race and socioeconomic lines—and often, both.

Gary Orfield, a researcher at UCLA who has studied integration and re-segregation in public schools extensively, says segregating housing policies and a lack of follow-through on integration court orders has stalled integration attempts in the U.S. In 1991, the U.S. Supreme Court authorized school districts to stop enforcing integration, which largely ended any efforts to integrate schools on a national level.

"There hasn't been any effective desegregation plans on the demographics for a quite a long time, but the demographic changes continued because it was mostly driven by the housing market all along," Orfield told the Jackson Free Press.

Orfield and a team of researchers work on the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, which produced the "Brown at 60" report in 2014. The report found that enrollment trends in the schools between 1968 and 2011 show a 28-percent decline in white enrollment, a 19-percent increase in black enrollment, and a 495-percent increase in the number of Latino students. As resources track lower in those schools due to decimated tax bases to support them, the quality of the education and the teachers tend to drop, keeping an under-educated generational cycle going for populations who were not originally allowed access to quality education.

"One of the reasons that racial segregation is harmful is the strong connection between schools that concentrate black and Latino students and schools that concentrate low-income students," the Brown at 60 report says. "Prior Civil Rights Project reports have referred to this as double segregation (e.g., segregation by race and class), and we continue to see the strong relationship between the two when examining segregation in schools in 2011-12.

"In 2011-12, 45.8 percent of all public school students were classified as low-income, meaning that they were eligible for free and/or reduced lunch."

In JPS, 99 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced lunch, as determined by federal poverty guidelines. Orfield and his team found that in deep southern states, including Mississippi, black students make up at least one-third of the states' enrollment in public schools.

This data matters because it affects black students' performance in school and then keeps the cycles of poverty and under-performance going for future generations.

A 2010 study, "Schools and Inequality," analyzed student performance and race data, mirroring the Coleman Report, published following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to document the correlations between race and student performance. The report unearthed the lack of "equality of educational opportunity" in the country.

University of Wisconsin researchers in 2010 found that "going to a high-poverty school or a highly segregated African American school has a profound effect on a student's achievement outcomes, above and beyond the effect of individual poverty or minority status. Specifically, both the racial/ethnic and social class composition of a student's school are 1-3/4 times more important than a student's individual race/ethnicity or social class for understanding educational outcomes," Geoffrey Borman and Maritza Dowling, who published the research, wrote.

Their research found that racially segregated schools are hindering African American students' ability to achieve.

"(It) is clear that racially segregated schools compromised African American students' opportunity to achieve educational outcomes equal to those of their peers at majority-White schools," the study says.

"... (T)his analysis suggests that both within-school interactions among students and educators, and racial segregation across schools deny African American children equality of educational opportunity."

School composition, and what happens inside the walls, can affect the performance of that school, in other words, as well as outside factors contributing to students' well-being including poverty.

Richard Kahlenberg, a writer and senior fellow at the Century Foundation, cites a study on housing policies in Montgomery County, Md., where low-income students were allowed to attend fairly affluent schools and live in middle to upper-class communities with remarkable results. The study compared those students to their peers living in majority low-income neighborhoods and attending schools with new and innovative resources.

"The results were unmistakable: low-income students attending more-affluent elementary schools (and living in more-affluent neighborhoods) significantly outperformed low-income elementary students who attend higher-poverty schools with state-of-the-art educational interventions," Kahlenberg writes in a paper titled "From All Walks of Life."

Ultimately, the Montgomery County housing policy had the most significant, positive educational impact for low-income kids in that county. It follows that black students attending more affluent schools, largely outside Jackson, perform better than low-income students in predominantly low-income schools in the city.

Clinton, Pearl and Madison County public school districts, the three most integrated districts in the Jackson metro, received "A" grades in the 2017 accountability results. The median household income in Clinton is $55,486, in Pearl is $42,323 and $64,376 in Madison County. The median household income in Jackson is $32,250.

Back to 'Separate But Equal'?

Hispanic students outnumber white students attending the 58 schools in JPS today, although 96 percent of the school district is African American. At some point in the mid-2000s, Womack says PPSJ shifted its focus, while still fighting to ensure the best education for everyone attending public schools. It was clear that keeping middle-class families, both white and black, in the school district had become too difficult.

"It would start around middle school and parents whose families who were die-hard public-school people would move to Madison County. Parents who wanted to stay in Jackson would choose a private school," Womack said.

Orfield says that while private-school enrollment is trending downward nationally, those institutions are getting whiter. The decline in private-school enrollment is among predominantly minority students, so while private schools get whiter, the public schools get less integrated—leading to the re-segregation of public schools.

While the racial composition of Jackson Public Schools stayed solid throughout the 2000s, the academic performance of students deteriorated. Then, despite bringing in an out-of-state superintendent, Cedrick Gray, the district persistently received a "D" grade for most of his tenure, until 2016 when it received its first marks as a "failing" school district. During this time, enrollment data show that white students, as well as some black students, steadily left JPS to go elsewhere.

Rankin County School District's population jumped from 13,663 in 1994 to 19,205 today, and while the majority of the student body there is white, the number of black students steadily increased every year. Similarly, Madison County Schools increased in student population each year.

Indigo Williams' son has seen the difference between schools in Jackson Public Schools and Madison County Schools. She is one of four mothers suing the state in federal court for failing to provide a "uniform system of public free public schools."

The lawsuit, brought by the Southern Poverty Law Center, points out the difference in facilities and academic rigor between the two schools. The lawsuit is not asking for integration, however. "Our case really isn't about segregation as much as it is about a lack of uniformity," SPLC senior staff attorney Will Bardwell said. "When you've got these schools that are overwhelmingly black, and you compare those to schools that are overwhelmingly white, and you can see dramatically different results, then something has gone wrong."

Uniformity for Williams' son would mean that he could attend a school that is equal to that of Madison Station Elementary School's academic rigor and resources.

"While at Madison Station, J.E. had access to experienced teachers, fresh food in the cafeteria, a host of creative classes, an array of afterschool programming and a modern computer lab," the lawsuit says.

"In contrast, at Raines (Elementary), J.E. first-year teacher had 32 students in her class at the beginning for the school year and not enough resources to support the needs of her students."

The lawsuit seeks declaratory relief for the court to declare the State of Mississippi adhere to its 1868 constitutional educational clause to provide a "uniform system" of public schools. "Uniformity means offering kids, no matter where they are in the state, the same chance to get a meaningful education that prepares them to participate in the political process," Bardwell said.

John Sewell and his wife, Kim, who are both white, made the conscious choice to send all three of their children to Jackson Public Schools at one point despite both attending private schools in Jackson themselves. Two of the couple's three children currently attend JPS in the Murrah feeder pattern, and Sewell says his kids attended McWillie Elementary and then tested into Bailey APAC Middle School.

Even though his kids are minorities in their classes, he said they do not see it that way and believe going to schools where they are the minority is important for their futures. "Building a healthy worldview is not something that should happen when you go to college. I think, you know, just being in a diverse group of people from the time you're 7 years old is not an unhealthy thing, and it just builds a mindset that's healthy," Sewell said.

One of Sewell's children attends St. Andrew's, he says, to take more challenging math courses like pre-calculus that were not offered at the right grade level for him to benefit in JPS. "Him moving to St. Andrew's is not saying JPS is not a good place to get an education," Sewell clarified. "I think it's a compliment to JPS that he's moving to a place that's harder because of the foundation that he's built."

Similarly, Sewell says he does not disparage parents who choose private schools.

"I don't knock anybody who does the private-school route. Everybody is going to do what they think is best for their child or children, but for us it comes down to our core beliefs and our faith," he said. "We think Jackson is a great city, and the people who live here are good, and we want to support things that make more good people."

Not all kids in JPS have the option of looking at private schools, and the now second-largest district in the state recently fended off state control, at least for now.

Walker, who was heavily involved in her daughter's education on both her middle school and high school PTAs, made sure Alexis participated was exposed to different kids. Alexis participated in clubs like the Civil Rights and Liberties Club, where she was able to meet and befriend some white kids. By and large, however, the district is homogenous in nature with a scarce chance of changing any time soon.

Today, some JPS students, especially at schools such as Jim Hill, say they seldom interact with white people at all.

Orfield suggests regionalism or magnet schools as a way to integrate schools, but regionalism requires the appetite for busing kids across district lines and for predominantly white communities to opt to attend majority black schools. If a community is fairly integrated itself, then bridging the school integration gap gets easier.

"If you can manage to hold so the neighborhood stands to be integrated, what many whites want isn't just to just flee continuously, they just want to be in a school that gets their kids ready for college," Orfield said. "(They want) a school where their kid isn't the only white kid. You have to plan to do it."

Black families in Mississippi, however, want a chance at a school system and resources they were promised over and over again, but ultimately never received on an equal basis—as majority politics in Mississippi since 1969 have increasingly focused on rewarding "good" districts and giving fewer resources to "failing" districts.

Walker mentioned DeSoto County Schools as the state’s largest district (JPS was the state’s largest district, until with enrollment declining, DeSoto surpassed JPS in student population in 2008) with adequate resources. DeSoto County Schools is also 52-percent white, a number that has steadily decreased over the past decade. Walker also pointed to school districts like Madison, Rankin and Pearl.

“They have a lot of money, and we don’t have the money,” Walker said. “So, I think integration would be great if we could bring those students into our population because the money would be different because the schools would be looked at differently.”

Walker, Huffman, Gibbs and Larkin experienced the beginning of a short-lived integrated Jackson Public Schools, which re-segregated rapidly in the next 47 years. At present, the district is focused on turning around academic performance, amid a governor-run takeover, involving multiple organizations and nonprofit groups. The problem of re-segregation by both race and class, however, remains untouched.

Gibbs and his wife, Debra, who is now a state representative, chose to send their two children to JPS schools despite their financial ability to send them elsewhere. Gibbs said the re-segregation of public schools in Jackson by both race and economics is disappointing.

“It started back with integration because a lot of the white parents then took their kids out, and now that has continued. … It’s not only separation by race but also separation by economics,” he said.

“I think some of the challenges we’re having in our public schools now is because people of economic means and educational means and people who have the experience that can go in the school and help with some of the issues that they’re having, they all pull their kids out and put them in private schools. That means that the population that we have in Jackson is not only mostly African American but it’s also lower socioeconomic, which also has some bearing on the ultimate results.”

Investigative journalist and MacArthur fellow Nikole Hannah-Jones has thoroughly documented the interaction of segregation by socioeconomics and race in her rigorous reporting on segregated schools. Hannah-Jones, who is black, chose to send her daughter to a segregated school, on the premise that at least they would be integrating it economically. She found in her reporting that many white parents would not even give that option a chance.

The State Takeover of JPS

JFP's stories about the state takeover of the Jackson Public Schools district

“True integration, true equality, requires a surrendering of advantage, and when it comes to our own children, that can feel almost unnatural,” she wrote in a 2016 piece for the New York Times Magazine.

That societal need is a main reason Gibbs said he and his wife made the decision to keep their kids in JPS.

“(If) all people of means took their kids out of public schools, there would be no parents or people who had the time to leave work and go to the school and volunteer or push the teachers to do better, push the administration to do better,” Gibbs said. “It would leave our parents, who are usually working two jobs or just don’t have the time, to do those things, so we just kind of felt a mission that we were going to be advocates for public schools, and we were.”

Today, Gibbs said he wants to see an integrated JPS in every way because everyone involved, and society over all, would benefit. "I would love to see the schools become more integrated, not only racially, but economically as well," he said.

Correction: A previous version of this story story mis-named the song "Good Ship Lollipop" as "Bishop Lollipop," in a quote from Mr. Gibbs. We apologize for the error. The print version of this story said Huffman and his classmates who edited "Lines Were Drawn" graduated in 1971. They graduated in 1973. We apologize for the error--it has been corrected online. Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected].