Friday, November 23, 2018

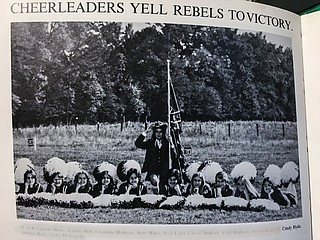

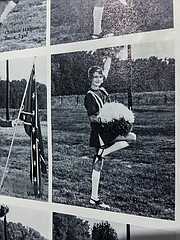

U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith appears third from the right in a 1975 yearbook photo of cheerleaders at Lawrence County Academy. The mascot appears in the middle dressed as a Confederate colonel holding a rebel flag.

JACKSON, Miss. — U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith attended and graduated from a segregation academy that was set up so that white parents could avoid having to send their children to schools with black students, a yearbook reveals.

A group photo in the 1975 edition of The Rebel—the Lawrence County Academy Yearbook—illustrates the point. High-school cheerleaders smile at the camera as they lie on the ground in front of their pom-poms, fists supporting their heads. In the center, the mascot, dressed in what appears to be an outfit designed to mimic that of a Confederate general, offers a salute as she holds up a large Confederate flag.

Third from the right on the ground is a sophomore girl with short hair, identified in the caption as Cindy Hyde.

The photo, and the recently appointed Republican senator’s attendance at one of the many private schools that was set up to bypass integration, adds historic context to comments she made in recent weeks about a “public hanging” that drew condemnations from across the political spectrum.

‘No Doubt That’s Why Those Schools Were Set Up’

Lawrence County Academy opened in the small town of Monticello, Miss., about 60 miles south of Jackson, in 1970. That same year, another segregation school, Brookhaven Academy, opened in nearby Lincoln County. Years later, Hyde-Smith would send her daughter, Anna-Michael, to that academy.

Hyde-Smith graduated from Lawrence County Academy in 1977, meaning she would have already been in school elsewhere at the time the academy opened.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court ordered public schools to desegregate in 1954 and again in 1955 to do so with “all deliberate speed,” Mississippi slow-walked the integration of its schools as long as possible, trying a variety of “school choice” schemes, state legislation and court cases to stop full integration, including arguing that white kids should not go to school with so-called "genetically inferior" black students.

Fifteen years after school integration become the law of the land, the Supreme Court ordered the immediate desegregation of public schools in 1969, and Mississippi Gov. John Bell Williams ordered that public schools integrate when students returned from Christmas break in early 1970. “So let us accept the inevitable that we are going to suffer one way or the other, both white and black, as a result of the court's decree,” he said at the time.

It is no coincidence that the academy Hyde-Smith attended opened the very year after the highest court’s ultimatum, as did others around the state. The day he announced his compliance, Williams made it a priority to focus on private schools as an alternative for white students whose parents were not keen on their children sharing classrooms with black children. The Legislature even approved private-school vouchers for white families to offset the costs of sending their kids to whites-only private schools.

“Lawrence County Academy started because people didn’t want their kids going to school with minorities,” Lawrence County NAACP President Wesley Bridges, who also serves on the local public school board, told the Jackson Free Press on Saturday. “That’s been evident.”

“Cindy Hyde-Smith was a product of that school,” he added.

Rep. Shows: 'I'd Do Anything for Her'

There’s “no doubt that’s why those schools were set up,” said former U.S. Rep Ronnie Shows, a Democrat who was Hyde’s junior high basketball coach at Lawrence County Academy in the 1970s. He served as the representative for Mississippi’s fourth congressional district from 1999 to 2003.

“She was always a great person back in those days,” Shows told the Jackson Free Press Friday. “I called Cindy and talked to her about this campaign, and I told her I loved her, and I’d do anything for her.”

He will not be supporting the senator’s bid for election Tuesday, though. When a video surfaced on Nov. 11 of Hyde-Smith saying she would “be on the front row” if a constituent asked her to go to “a public hanging,” it was just another black eye for perceptions of the state, he said today. If her Democratic opponent, Mike Espy, is not elected, Shows said, “it just reinforces” the worst stereotypes about the state.

Espy, a former congressman who served as U.S. secretary of agriculture from 1993 to 1994 under President Bill Clinton, would be the first black U.S. senator from Mississippi since the post-Civil War Reconstruction era.

“I told her, ‘There’s nothing I couldn’t do for you, but I can’t do this for you,’” Shows said he told Hyde-Smith about voting for her.

Hyde-Smith’s ‘Public Hanging’ Quip Bombs in State with Most Lynchings

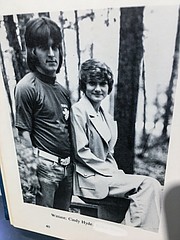

Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith created a firestorm with her remark about "public hangings" as she faces off against black opponent Mike Espy.

After Lamar White, an independent journalist who writes the Bayou Brief, published the “public hanging” video, people all across the state, including many African American leaders, pointed to the state’s history of lynchings that targeted African Americans. Mississippi was the worst perpetrator of racially motivated lynchings of any state in the South. Hyde-Smith’s campaign responded by saying the “public hanging” remark was just an “expression of regard” for a supporter and called the concerns “ridiculous.”

‘It Was All About the White Guy, Right?’

Many Mississippians scratched their heads. It seemed no one had ever heard the alleged colloquialism, “If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.” The New York Times, though, interviewed a southern linguist who said the expression was used in the late 1800s and early 1900s—when lynchings were most common—but had mostly died out by 1950. Hyde-Smith was born in 1959.

Shows, however, said he recalled hearing the expression growing up.

“I heard it in passing, not as a joke,” he said. “Coming up back then, I didn’t know the impact until I got older and started reading to find out, and I was shocked. You’ve got to remember that we didn’t study black history then—it was all about the white guy, right? I’m not making excuses. It’s crazy running for office in Mississippi to say that.”

Hyde-Smith refused to comment on the video for over a week, but finally offered a pre-written milquetoast apology at the Nov. 20 debate with Espy, only to cast the blame on him and accuse him of twisting her words for “nothing but personal and political gain.”

In fact, Espy and his campaign first learned of the video when the Jackson Free Press called them for a comment shortly after it surfaced.

Shows attributed Hyde-Smith's refusal to offer a proper apology to her “following Trump”—the president whom she’s clung to throughout the campaign and whom she reminds voters she has voted with “100 percent of the time.”

“Have you ever heard Trump back off something?” Shows said.

Even though Shows has endorsed her opponent and thinks her victory would be a stain on the state, he does not think of the woman he once coached as a bigot.

“I don’t think she’s a racist,” Shows said. “I just think she’s got a lot of constituents who are racist. You know we have them.”

She ‘Should Not Get a Pass’

The yearbook, provided to the Jackson Free Press by a former student who asked not to be named, is one of very few pieces of evidence still available that identify the segregation academy as the recently appointed senator’s alma mater. While Hyde-Smith regularly touts her subsequent education at Copiah-Lincoln Community College and the University of Southern Mississippi, her high school has been conspicuously absent from the senator’s official statements, speeches and public biographies. Even her Facebook account suggests her education began with community college.

In that reticence about her high-school years, Hyde-Smith is like the man who appointed her to the U.S. Senate seat, Gov. Phil Bryant, who attended one of the Citizens Council academies set up around Jackson by the virulently racist organization for white families fleeing newly integrated schools. Local newspapers treated announcements from those schools about sports and other honors the same as public schools, while running photos of children with a “Citizens Council: States Rights, Racial Integrity” placard in front of them.

Bryant also does not publicize that he attended Council McCluer School in south Jackson, which a local historian confirmed through yearbooks for a column in the Jackson Free Press last year.

Former Mississippi Democratic Party Chairman Rickey Cole, who knew Hyde-Smith when she was a Democratic state senator before she became Republican in 2010 to run for state agriculture commissioner, said Hyde-Smith would have known why she was at a school like Lawrence County Academy.

“When the public schools in Mississippi were ordered desegregated, many thousands of white families cobbled together what they could laughingly call a school to send their children to for no other reason except they didn’t want them to be around n-words or to be treated or behave as equal to black people,” Cole said.

Cole attended a public school in Ellisville, Miss., and recalls making fun of the kids in town whose parents drove them 26 miles to Heidelberg Academy and back—more than 100 miles a day—just so they could have a substandard education with teachers who often had little more than a high-school diploma.

“The only reason people of my generation and Cindy’s generation went to segregation academies was to keep the white kids and the black kids apart,” said Cole, who added that he is about six or seven years younger than Hyde-Smith.

The student who provided the Jackson Free Press with the yearbook said she realized her parents had sent her to Lawrence County Academy to keep her from going to school with black students sometime while she was still a student.

“That was just between the family, and we found out when we were old enough to question it,” the student said. “That’s how our parents felt. I didn’t learn it from anyone in the administration.”

The student was younger than Hyde-Smith, and though she knew of her, she said she was too young to have any sort of relationship with the future politician.

Lawrence County Academy shut down in the late 1980s due to dwindling attendance—one of the now-defunct early schools that sprang up in response to integration. Among those that survived, though, was Brookhaven Academy, where Hyde-Smith chose to send her daughter, Anna-Michael. Many started recasting themselves as Christian academies, later admitting students of color; Council McCluer, for instance, became Hillcrest Academy.

Cole said Hyde-Smith “should not get a pass” for her attendance at a segregation academy, nor for later sending her daughter to one.

“Socially, instinctively and intuitively, I know why these things happened, because it’s what we all lived through,” Cole said. “For the younger generation, though, this will be big news to them. Hell, it might even be big news to Cindy’s daughter. That’s the way it always was, and we were very much separate and unequal.”

As of Friday night, the Hyde-Smith campaign was not prepared to comment on this story because it was too late for campaign communications director Melissa Scallan to speak to the senator, but this story will be updated if Hyde-Smith does decide to comment.

The Academy and the Council

Even to this day, Brookhaven Academy, from which Hyde-Smith’s daughter graduated in 2017, is almost all-white. In the 2015-2016 school year, Brookhaven Academy enrolled 386 white children, five Asian children, and just one black child, the National Center for Education Statistics shows. That’s despite the fact that Census statistics show Brookhaven is 55 percent black and 43 percent white, per 2016 Census estimates.

"That pretty much tells me that she’s a true conservative," Bridges, the NAACP president, said of Hyde-Smith's decision to send her daughter to a private school. "Conservatives do not really care for minorities or poor white people. A child doesn’t have a choice of where their parents send them to school, so she grew up as a child in a private school that was set up so white parents could keep their kids from going to school with African American children, and then sent her child to a private school. This is a broad generalization opinion, but I think 90 percent of the people that send their kids to private schools do it so their kids don’t have to go to school with minorities."

Facts about Mississippi, Secession, Slavery and the Confederacy

The JFP’s archives of historically factual stories about slavery, secession and the Civil War in Mississippi, with lots of links to primary documents.

In Trent Watts’ 2008 book, “White Masculinity in the Recent South,” the historian and Brookhaven native recounts an episode in which tensions over the local private academy came to the fore.

“People, white and black, but whites especially, did not want bad publicity for Brookhaven,” Watts wrote. “They didn’t care if someone threw a rock, as long as nobody saw who threw it.”

In 1988, Brookhaven High School hired a football coach named Hollis Rutter, who had worked previously at Brookhaven Academy, and the veneer of colorblindness was rent in two. White Brookhavenites were taken aback when black residents decried the decision to bring in a coach from a segregation academy.

"This association with noxious institutions caused practically all black Brookhavenites to perceive Rutter as at least a tacit supporter of segregation,” Watts wrote. “In their eyes, his authority as coach and his privilege to mold young men was fatally compromised; what masculinity gave, race (or rather, black perceptions of his racism) took away.”

Black ministers, NAACP leaders and black students banded together for a 10-week boycott of every facet of the town. That April, 200 black students in the school district walked out of class, with students at Brookhaven High removing the state flag from the flagpole outside the school as they went.

The high school’s boys’ basketball team was reduced from 24 players to just eight, and the ninth-grade basketball team’s entire season was cancelled because there was no longer a team at all. White nationalists descended on the town to counter-protest. White business leaders, though, panicked, and soon convinced the school board to rescind its decision to hire Rutter so that regular life could resume.

While the town’s white residents felt blindsided by the outrage over the hiring, it did not happen in a vacuum. Even before desegregation brought the advent of segregation academies, Brookhaven had inflicted its own special brand of pain on its black residents.

Led by the (White) Citizens Council

A major force behind the segregation academies was the white-supremacist organization officially called the Citizens Council and routinely referred to as the "White Citizens Council." Brookhaven was the home of Judge Tom Brady, a white supremacist who authored “Black Monday,” the organization’s 92-page semi-official handbook soon after the Brown v. Board decision. In it, he made the case that those with “negroid” blood were inherently inferior to white people. The booklet functioned as a guide for the founding of the Citizens Council in July 1954 by Robert “Tut” Patterson, a former Mississippi State University football star.

The Lies Scientific Racists Told About Jackson’s Children

The Citizens Council, based in Jackson, published lies about the inferiority of African Americans for decades. It also ran whites-only academies.

In the February 1972 issue of the Council’s official publication, The Citizen, the racist organization described its work to enroll white children in private schools.

“It is in Mississippi that thousands of white parents have enrolled their children in the Council School Foundation's private school system rather than accept the degradation of forced race-mixing, and mass bussing of pupils as ordered for public schools by the federal courts,” the article reads.

In a 1974 issue, The Citizen touted a program to help white parents in Brookhaven pay for their children to attend Brookhaven Academy.

The Citizens Councils of America, based in Jackson and run for years by William J. “Bill” Simmons, the previous owner of the Fairview Inn, officially folded in 1989. By that time, another organization started using its national mailing list. The Council of Conservative Citizens, launched in 1988, held similar white-supremacist views against miscegenation (insisting that race-mixing would destroy “racial integrity”) and pushed stories about black-on-white crime to hype the violence of African Americans. That group raised money to support the state’s segregation academies every year at the Blackhawk Rally in Carroll County, one of the state’s two most popular gatherings for political campaign speeches, alongside the Neshoba County Fair.

Mississippi politicians from former U.S. Sen. Trent Lott, Gov. Haley Barbour and Gov. Kirk Fordice, to current Mississippi Senate Tourism Chairwoman Lydia Chassaniol have spoken to or had close associations with the CofCC.

The Council of Conservative Citizens is also the organization that Dylann Roof cited in his racist “manifesto” as the inspiration for his massacre of nine black worshipers at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C., in 2015.

‘She Was Scared to Death of Race’

Brookhaven’s oppressive race history, like anywhere else in Mississippi, did not begin with the academy.

On Aug. 13, 1955, Lamar Smith, a black civil-rights activist, was helping black voters fill out absentee ballots for a local election so they could avoid the harassment of voting in person when three men began shouting at him. An altercation broke out, and one of the men, Noah Smith—an unrelated white man—drew a pistol and shot Lamar Smith in front of a crowd of dozens of witnesses.

Neither Noah Smith nor the two men who were with him were ever indicted for the slaying; the witnesses all told a grand jury they had not seen a crime.

Against this backdrop, Cindy Hyde was born four years later.

Brookhaven at the time of her birth and youth might seem like a crucible for the story of race in America, but according to the ex-chairman of her former party, race has always made Hyde-Smith uncomfortable.

Cole recalled her time as a Democratic state senator, and said he believed the demographic makeup of Brookhaven is part of the reason why she is uncomfortable. It was also during the time when members of the old racist Democratic Party were still transitioning into the new Republican Party that realigned to welcome old “Dixiecrats” frustrated that national Democrats supported civil-rights legislation in the 1960s.

“She was scared to death of race because she was a Democrat in a district where she depended on black votes, and she knew that she had to at least give the appearance of being friendly to African American constituents, but she was mortally terrified of being overly identified with black constituents,” Cole said, adding that “the legislators she hung with were white legislators.”

After getting elected to the Mississippi Senate in 1999, Hyde-Smith took up an effort to pass a law to rename a highway after Confederate President Jefferson Davis. While some have pointed to that as evidence of her affinity for the “Lost Cause” revisionist romanticization of the Civil War, Cole takes a more pedestrian view of her actions. More likely, he said, someone from the Sons of Confederate Veterans asked her to do it, because “it wouldn’t occur to her” to do it on her own.

“If you asked Cindy what time it is, she would say, ‘I don’t know, what do you think?’” Cole said. “Playing both sides, that’s what she does.”

Cole said that probably explains why Hyde-Smith is one of just two U.S. senators not to display the state flag outside her office in the Washington, D.C., Capitol. Because of its Confederate symbolism, Mississippi’s other U.S. senator, Roger Wicker, does not display the flag either, and called for it to be changed in 2016.

“Wicker doesn’t display it, so she doesn’t display it,” Cole posited. After the Nov. 20 debate, Espy spoke with the press. Hyde-Smith, though, sent Wicker out to speak on her behalf, insisting she had to get back to her husband.

Cole suspects Hyde-Smith left the Democratic Party and ran for agriculture commissioner as a Republican because she realized it had become “too closely identified with black people,” he said. “Republicans were either going to beat her in that state senate race, or she was not going to get that nomination again.”

'The South Was Right'

Gov. Bryant, who appointed Hyde-Smith to the U.S. Senate after Sen. Thad Cochran resigned due to health in April, is a dues-paying members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Every April, the Jackson Free Press revealed in February 2016, Bryant proclaims “Confederate Heritage Month.”

Gov. Bryant Proclaims Confederate Heritage Month

The Jackson Free Press revealed to the world in February 2016 that Gov. Bryant had declared April "Confederate Heritage Month," but with no mention of slavery.

When Hyde-Smith’s daughter graduated from Brookhaven Academy in 2017, Bryant appeared to give a commencement address to her class of just 34 students as a gift. A story from The Daily Leader at the time features a photo of Bryant, Anna-Michael Smith and Cindy Hyde-Smith all astride horses as they take part in the Dixie National Rodeo. It is an event Hyde-Smith’s farm-raised family participates in yearly, alongside people of other races, including African Americans.

Hyde-Smith shared a series of photos on her Facebook page in 2016 of her and her daughter at the parade. In several of the photos, though, other attendees carry Confederate flags. Her photos included a group of men dressed as Confederate soldiers marching with the flag of the Dixie Alliance, a group that maintains that the South was right to secede from the union to enter the Civil War.

“Since the end of the War for Southern Independence (some call it the Civil War),” reads the Dixie Alliance website, “decades of time, Leftist influences, and unconstitutional federal actions have proven that the South was right to exercise its moral and legal grounds to declare independence.” Through its work, the group says, “Leftist influences will decline, division and hatred will subside, and the symbols and monuments of the Confederacy of America will be preserved.”

Earlier this week, a photo Hyde-Smith posted on Facebook in 2014 surfaced, showing her wearing a Confederate uniform as she toured Beauvoir in Biloxi—the historic home of Confederate President Jefferson Davis where you can buy books like “The South Was Right.” “Mississippi history at its finest,” Hyde-Smith captioned the photo. Beauvoir is owned and managed by members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who, like the Alliance, seek to recast the South’s role in the Civil War in a positive light.

Hyde-Smith has made no explicit endorsement of groups like the Dixie Alliance, nor has she made it a cause to defend the state flag or Confederate monuments. Like segregation academies, Confederate uniforms, Dixie parades, and colloquialisms that recall Mississippi’s history of lynching, however, it is another detail of her life that demonstrates the ubiquitous, and at times banal, nature of the role of white-supremacist culture in her upbringing and adult life.

Hyde-Smith Faces Espy in Debate, Nov. 27 Runoff

No matter who wins, the Nov. 27 runoff will be historic. When Gov. Phil Bryant appointed her, Hyde-Smith became the first woman to represent Mississippi in Congress and could be the first duly elected come November. If Espy wins, he would be the first black U.S. senator from the state since Reconstruction, when Sens. Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce represented the state in Washington, D.C., until the end of Reconstruction brought the disenfranchisement of black voters.

Around 900,000 Mississippians voted in this year's election—a midterm turnout record of 40 percent, up from 29.7 percent in 2014. Anyone who registered to vote by Oct. 29 will be eligible to vote in the runoff, even if they could not vote in the Nov. 6 election. Voters must have a valid form of photo ID, such as a driver's license or student ID. The Secretary of State's website has a full list of acceptable forms of ID. Polls are open in Mississippi from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Ashton Pittman covers politics and elections for the Jackson Free Press. Follow him on Twitter at @ashtonpittman. Email him at [email protected]. Read more 2018 campaign coverage at jacksonfreepress.com/2018elections.

Donna Ladd also contributed to this report. Read her story about white Mississippians who have changed their minds about racism. To learn more about the Confederacy, and its myths and facts, see jacksonfreepress.com/confeds.