Friday, November 8, 2019

Another Mississippi media outlet “aggregated” Donna Ladd’s Guardian story about Benny Ivey with a man’s byline on it, then trashed her on Twitter for pointing out their error. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

What a week. The last 10 days saw not only the demise of the Mississippi Democratic Party, at least the way it's run and strategized now, but the period was filled with disillusioning encounters with local representatives of national media corporations for us, revealing a certain callous regard of other reporters and editors.

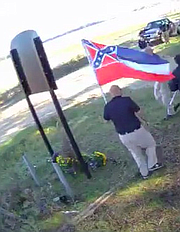

The most frustrating example came after our state reporter, Ashton Pittman, got a tip and video Saturday afternoon from a source I've known a long time at the Emmett Till Center about white supremacists gathering at the new, bulletproof marker for the 14-year-old boy racists killed in 1955. Ashton texted me that he had the video and was writing it up to get out by Saturday evening. I was out shopping with Todd and rushed back home to edit the story and to help get three videos on our website. Meantime, Ashton tweeted parts of the videos, which went viral quickly.

The Emmett Till Center soon posted the videos on its site as well, and its followers started swelling as Ashton's tweets and stories were shared. Contributions also started rolling in to the Till Center in Sumner, Miss.

By Sunday, of course, other media were following up the story, as they should. But oddly, outlets weren't crediting Ashton and the Jackson Free Press for breaking the story—even though Ashton's work Saturday was clearly the reason they knew about it. Outlets including the Associated Press and NBC News published stories Sunday that didn't mention the original story that others picked up on.

White Supremacists Caught at Emmett Till Memorial Making Propaganda Film

Read Ashton Pittman's breaking story and see video of white supremacists scurrying away from the Emmett Till marker when alarms went off.

To those outside the journalism industry, this may not seem like a big deal. But it's considered a breach of journalistic ethics to not credit the original journalism outlet that alerted you to an "enterprise" story. "Enterprise" means that a journalist got a story not because a press release went out and he slammed it online first; it includes doing the digging and hard work to break it yourself, and it includes the publication having the kind of sources that trust you with the story first. And a strong source network is the heart of good actually-local journalism.

The Till Center itself gave credit to Ashton's work on Sunday. "Thanks to @JxnFreePress for leading the charge on this important story," it tweeted with a retweet of one of my Sunday tweets: "Results of #EmmettTill piece: raised around $10K for @EmmeTillcenter since Saturday night; showed that there are cameras and alarms at site now; raised more awareness about young Emmett; and public helped figure out who was there (below) with, apparently, one more to go. #impact."

Then, on Nov. 5, The New York Times ran its story on the incident and handled the attribution professionally, naming the newspaper and linking to our story. (That wasn't so hard, huh, media?)

This isn't about ego: getting proper credit not only helps avoid charges of plagiarism but also helps amplify local journalists like Ashton and small newspapers like mine that can struggle for mindshare or page views among the national noise. In turn, it helps our other deep, award-winning reporting of the last 17 years get more attention, which in turn helps our community and state. And it makes it clear that there is excellence in home-grown Mississippi journalism. And, of course, Ashton's story gave more context than any other outlet managed to give on Sunday to the story because that's how we roll.

The ongoing problem of skipping attribution is part of a national dialogue over corporate media not giving proper credit to the journalists who actually originate a story. Often, those ignored journalists work for local media outlets like mine and, way too often, are women.

But when I called out those outlets, and a couple local TV stations, on Twitter for the need to add Ashton's attribution, one reporter for a national corporate-owned outlet in Jackson did something I've seen too many times to count now. He blamed us for trying to make the story about us rather than just saying "our bad" and adding the link (which we have done if told we left off an attribution; it costs us nothing to do the right thing). And then he responded to me with a personal insult that had nothing to do with my asking for proper attribution. Readers were backing up our request as well.

I can also add that women really get hit with this response if we ask for attribution, even though we watch male journalists fight over credit for who published a damn press release first. It's a form of gaslighting, rather than just saying "my bad" and adding a link. Years ago, an international TV producer partnered with me and photographer Kate Medley to investigate a cold Klan murder case in Mississippi. His pitch to us was that he would document Mississippi journalists seeking justice in a cold KKK case. My goal was to investigate a case not involving white victims as most media seemed to do, as Rita Schwerner Bender had pointed out standing on the lawn in front of the Neshoba County courthouse the day Edgar Ray Killen was finally convicted for helping kill her husband in 1964.

I Want Justice, Too: Re-opening KKK Cold Cases in Mississippi

Investigation by Donna Ladd and Kate Medley of 1964 murders that sent an old Klansman to prison

"You're here, you're interested in this trial as the most important trial in the Civil Rights Movement because two of the men were white," Bender told the media standing under a big magnolia tree after the long-overdue verdict. "You're still doing what was done in 1964." Those words inspired me to look into the never-solved Dee-Moore case—and not just to put someone in prison. Both the Associated Press and Mississippi's most famous cold-case reporter had long reported the main suspect, James Ford Seale, as dead.

The producer later claimed full credit for finding a suspect alive, although he'd been reported dead, although we all figured it out while reporting together on the same trip, and on the same day—and we reported it long before he put anything out on it. Finding his alive wasn't hard at all; he was living in a trailer next to his brother's house, and everyone there knew it. All it took was hitting the ground and talking to people. An old Klansman told Kate an me during an interview.

Finding James Ford Seale was a collaborative effort, as my files and stories prove. We didn't expect or want full credit, but we also didn't anticipate efforts to cast our role completely to the side, to the point of someone constantly editing Wikipedia to write out our role early on. It was eye-opening.

Later, it felt good, though, to watch James Ford Seale's defense attorney work so hard in the James O. Eastland federal courthouse in downtown Jackson, and unsuccessfully, to keep our long series of stories out of evidence, however. Our goals were fulfilled, both with overdue justice, but also by publishing the kinds of stories that made the two young men the Klan killed come alive and show the inhumanity of not taking their deaths seriously.

I decided then, perhaps naively, not to make a big deal about being shut out precisely because I didn't want to make the story about me and my team; after all, we were all following a family member looking for justice after decades. It was his story. So I took the high road.

Like a Screechy, Crazy Woman

Last year, the Mississippi outlet that NBC News Chairman Andy Lack founded here decided to "aggregate" my Guardian piece about Benny Ivey and white gangs in Mississippi that I spent months reporting and writing—a story that was about as "enterprise" as you can get. "Aggregation" is basically summarizing another outlet's story to fill space on your website and to get easy page views. (It's something we don't need to do. Besides, we pay to subscribe to the Associated Press for stories we can't get to.)

But they didn't follow ethical aggregation standards. For one thing, one of their editors' bylines appeared under the headline, making my story look like his story. Then there were several paragraphs summarizing the story without attribution to me, just lifting content from my story without my permission. At the very bottom a subtle link was tucked in.

It was the worst attempt at "aggregation" I've ever seen. It was more like a blatant page-view grab. And it not only shocked and angered me, but also the subject of the profile who had spent so much time with me for it, and the local photographer, who put worked hard on the package for The Guardian.

I couldn't get anyone to pick up the phone in their Ridgeland office to tell them to take it down, so I posted in the comments underneath my work on their site. Then I heard from the managing editor whose name was on it, and he apologized kindly and took it down. That should have been the end.

But another editor and a reporter, both men, decided to punish me for calling out their mistakes. One claimed on Twitter that it was aggregated correctly, which was just absurd when you read best practices on aggregation, including from the Society of Professional Journalists. ("Always attribute information not independently gathered.")

The Rise of America's White Gangs

Donna Ladd reports for The Guardian on the largely ignored rise of white gangs in America, and how they're treated differently from black and Latino gangs. Photo: Imani Khayyam

Then get this: The reporter guy actually then dug around in my tweets looking for something to try to make me look bad—and like a screechy, crazy woman, I guess ("gaslighting"), instead of the professional journalist they tried to score page views from. The reporter found a years-old tweet about an incident with a national client where another editor (no longer there) had pulled out a quote from an exclusive interview I did and had another story written around it, mischaracterizing the original quote. That outlet apologized to me, and all was well.

But, somehow, my even briefly mentioning people mishandling my work—I had declined to talk to media about it then—to these men was outrageous behavior deserving punishment. Women really don't get to speak up for our work or that of our team? And from the examples we see around the country, women constantly get cribbed, plagiarized and then gaslighted for pointing it out—and not just journalists, but historians, scientists and others. (Follow women historians on Twitter to hear about this constantly.) The difference now is that we're speaking up about it. They've gotten away with it for so long precisely because we've stayed quiet—clearly a mistake. It's just license to keep doing it.

Add that to recent research that shows that male journalists retweet each other and lift other men's work up often, but not women's, and it is clear that women cannot keep being martyrs about theft of our own or that appears in publications we own. We should not suffer such disrespect in silence. That hurts women coming behind us.

Be clear: In no way does following journalistic ethics somehow take away from the impact of our work—the Klansman went to prison, the Emmett Till Center raised $30,000 within six days and drawn thousands more followers—to demand that we, too, get credit for spending months, or a Saturday night, doing a story others knew nothing about.

The effects of good work—whether funding, awards or career-building—should not just belong to a handful of men who didn't do the work in the first place or who want to claim collaborative work for themselves. It's time to call it out for what it is.

Not to mention, men have to learn that it is not acceptable to respond to a woman's legitimate concerns with personal attacks or by digging for dirt on us. Be bigger and more professional, guys. And apologies never hurt a flea.

Of Goliath and Localwashing

I also got interesting responses from some local male reporters recently when I noticed that The Clarion-Ledger, owned by a mega-corporation now merging with another one, has a new marketing phrase to try once again to claim the "local" mantle.

Now under their stories, a box appears that says: "LOCAL JOURNALISM MATTERS: Our journalists live, work and play in Mississippi. We are striving to make it a better place to live through the stories we tell. Please click here to support quality Mississippi journalism with a digital subscription."

On the surface, that's a pretty innocuous sales pitch, of course. It's also an obvious one. Where else would its journalists be living, working or playing, pray tell? (Although, the Ledger did move its copy editing and design operation to Nashville at one point, leading to some very unfortunate errors.)

With due respect, the fact that reporters eat locally does not make Gannett or now Gatehouse Media a "local journalism" outlet. I was in Cambridge, Mass., in June working on a story for The Guardian, and I ate a lot of great food and even visited a prominent cemetery for my piece, but that alone doesn't mean my journalism was local.

If you've read my paper for a long time, you already know that I know and have published a great deal about the corporate nightmare that The Clarion-Ledger, under Gannett, became after the purchase and Gannettification of so many actually locally owned newspapers a few decades back. In fact, the period just before Gannett bought the Ledger in was its hacylon era, sandwiched between its decades-long run of horrific racism and its current corporate ownership. (I think it's had six publishers since we launched 17 years ago; we know one found out he was fired when his key card didn't work.) Read a great piece Valerie Wells did about the "News Wars: Rise and Fall of The Clarion-Ledger."

After I first moved back to Mississippi in 2001, I remember two major things about the Ledger: It was all over helping Republicans pass "tort reform" in the state (which helped lead to today's GOP supermajority by lessening campaign funds to Democrats), and it was a statewide paper that was rabidly anti-Jackson, running the capital city's crime woes often on page 1 and with events listings that mostly sent people out of Jackson to do stuff.

Ironically, the Ledger by then was famous for its coverage of KKK cold cases, but its current reportage was ignoring ongoing systemic and structural racism as it was fixated on confirming the GOP's effort to use a "greedy black people" campaign to limit lawsuits. Not to mention, it turned local district attorney Ed Peters and his assistant district attorney Bobby DeLaughter into national heroes in the Medgar Evers case, even as they were engaged in the kinds of prosecutions of young black men that could ruin lives. Too bad they couldn't report both past and current racism or be held to that higher standard.

We launched in 2002 with a defiant think/live/shop local theme with the goal of helping rebuild pride in our majority-black capital city. We even ran a Best of Jackson ballot in our first issue—something that seemingly hadn't occurred to the Ledger or anyone else. Jackson—best?!? (Although we would have fights with them later over trying to name their own Jackson "best" contest similarly to ours. Sigh.)

Since then, what's fascinated and often disgusted me about Gannett and its various divisions is how hard they have tried to re-establish its paper as "local" in its satellite cities, even as it keeps laying off well-loved staffers (like Orley Hood here), and now openly runs USA Today sections instead of more local news it could be covering and putting into print.

In 2009, a Gannett property even trademarked ShopLocal(TM) and tried to use it on sites like the Ledger to hawk ... wait for it ... flyers from big-box outlets like Target. I called this out, the guy responded to me, a woman in Forbes came back at me, and we responded again. Let's just say, they were sensitive about the "localwashing" effort.

News Wars: The Rise and Fall of The Clarion-Ledger

Valerie Wells charts the history of The Clarion-Ledger from virulent racism, to a period of glory, back to darker corporate-journalism days under Gannett ownership.

Worse, many of you remember what we and other locally owned publications went through after a Gannett property called The Distribution Network, or TDN, started sending Ledger staffers around to our distribution spots acting like local publications were all in on them controlling our distribution there. Some distribution points signed agreements based on misinformation, and then The Clarion-Ledger physically removed our boxes (with papers in them) to an uncovered-but-locked local lot near the downtown post office if we wouldn't agree to pay them to distribute us. Several of our distributors cancelled the agreements when they figured out they'd been misled about our supposed participation.

Read lots of stories about the TDN debacle here.

Local publishers, led by my partner Todd Stauffer, fought back and drew national media attention. This cost actually-local publications—from Metro Christian Living to real-estate publications—a lot of resources and time we didn't have to fight, but we weren't going to let Goliath just take over and control (and thus diminish) our distribution. This also drew readers closer to us, helping to speak out against the corporation that thought it could walk all over the little guys. Eventually, we won, and TDN quietly picked up their boxes. It's why you still see the JFP along with other publications in big multi-boxes at gas stations and at grocery stories. We banded together to fight back.

Publishers of actually-local publications such as ours have long wrangled with Gannett and other corporate media in various ways—as several books detail like this classic and this on the Gannett disaster in Arkansas—and as I studied in-depth while at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism right before I came back to Mississippi and started the Jackson Free Press.

The big difference, beyond content, is that their business moves are about shareholder value, and ours are to make payroll, support actually-local businesses, build community and report truth to power, just as we did about Gannett throughout the TDN effort. We still appreciate the reader support we got in return.

When I saw that "local journalism" notice the Ledger and I'm sure other Gannett publications are putting under stories, this tough history and what it put us through flashed through my head. After I saw a good story by a newish Ledger reporter factchecking campaign ads, I retweeted it and an image of the "local journalism" box under it, adding, "Good to see Mississippi reporters factcheck TV ads. But, no, @clarionledger, you are decidedly not 'local journslism.' (sic) Just stop. No one believes that."

Even though I distinguished between the reporter's work and the corporate newspaper, some of its reporters took offense, responding that they eat and drink here, visit tourist sites and so forth. Look, that's great, and these new reporters are doing some good journalism (I share their stories often), but they missed my point, which was not directed at them. This is about the Goliath corporation they work for—the one that has laid off so many reporters with little dignity, including the best investigative reporter they ever had, who is winning awards with impactful work in another state now. And it's the corporation that tried to control my distribution using an unsavory and misleading strategy precisely because it thought it was too big for little local guys to stop.

Another (freelance?) reporter in the state quickly chimed in after my "local" tweet to take me down a notch or two. "Damn Donna, I bet you're a rage at parties," he quipped. I guess he hasn't seen those pics of me dancing on various bars or spinning records with hundreds of people sweating on a dance floor. I've always done OK at parties. I even used to make money by hosting them in New York City.

But Donna-the-party-girl is woefully irrelevant to this conversation.

That childish insult brings us full circle, though. Why such fragility toward a woman editor with decades of experience asking for proper attribution? Pointing out a mistake? Calling out hypocritical "local" corporate outlets? And now, I figure they will all talk about how "obsessive" I am to engage in this bit of media literacy with my readers. Whatever, boys.

Journalists can be an awfully skin-skinned bunch considering that we poke and prod constantly into other people's lives, often looking for their flaws and slip-ups. I always tell my students and reporters to develop a tough skin. Criticism happens, and people will try to discredit you, especially when you're right. Journalists must own our mistakes, and learn something from all feedback. Vitally: Never respond to discussion of real issues with an ad hominem attack, because it just makes you look silly. And always stay focused on what matters.

Oh, and never forget: Excellent work is always the best response.

Editor-in-chief and CEO Donna Ladd's Dossier appears every Friday at jacksonfreepress.com. Read more Dossiers at jacksonfreepress.com/dossier. Follow Donna on Twitter at @donnerkay. Read her blog at donnaladd.com and email her truth-to-power tips to [email protected].