Wednesday, December 9, 2020

Jasmine Watson is a registered nurse at the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s 2 North unit, which is consumed entirely with COVID-19 patients. The immense stress of the pandemic is a constant pressure on Watson and her colleagues. Photo courtesy UMMC Communications

Jasmine Watson recalls bringing her patients perfume. It is an odd memory, out of place juxtaposed against other scenes in her medical-surgical unit. "They want that sense of normalcy," she says, laughing warmly as she remembers. Perfumes and colognes, to fill in what is left of her patients' sense of smell with a taste of home, rather than the cloying scent of the hospital.

Perfume is common; so is fruit. Apples and bananas, anything bright and fresh to keep their spirits up. Some of the objects she carries up to her floor are utilitarian—phones and chargers, devices to distract, to keep in touch. She shepherds them from families outside the University of Mississippi Medical Center, where she works as a registered nurse, to her patients in a unit that coronavirus has swallowed completely. All of her charges are afflicted with it.

In the beginning, she told the Jackson Free Press in an interview, each nurse dealt with one COVID-19 patient. At this point, each of them is managing three. Their systemic symptoms make treatment significantly more taxing than typical cases. "They're still med-surg patients. But on top of that, they have COVID," Watson says.

Her charges are cocooned in technology, telemetry and pulse monitors to watch for a dangerous turn. Watson knows how quickly the disease can claim a life. She has seen it firsthand.

She has a patient in mind. The law bars her from sharing fine detail, so the portrait is a silhouette.

The patient was young, healthy, the kind for whom a hospitalization should have been a brief detour on the road to recovery. She left for the weekend, expecting her patient to be ready to discharge when she returned. When she did, her patient was gone.

That person's memory is still with Watson. But it carries less currency outside the boundaries of the hospital, where she finds herself surrounded by deniers not even willing to wear a mask. "People feel like you're telling them what to do," she said. "But we just don't want you laying in the hospital bed unable to breathe."

Time and the worsening crisis have worn the nurse's patience away. The last squabble she had was in the grocery store in line with someone looming behind her without a mask on. "I'm not really nice about it. I yelled 'COVID is real! Can we get a few feet behind me?'"

Paradoxically, the pushback against public health has only seemed to worsen with the crisis. Watson only experienced the final apotheosis of denialism last month. A patient in her unit refused to believe their diagnosis was real. "They told me I tested positive, but I don't believe it," the patient said. "I'm ready to go home."

Watson stays above the vitriol and does what she can for her patients, regardless of what they believe. "If people are convinced that they don't have something, you can't convince them they do," she lamented. But while the virus is invisible, the symptoms are undeniable. She treats them, and hopes to see them get better, knowing that the most important messages are often those left unsent.

"The people who can talk about their experience with the disease are the lucky ones," Watson says. Some stories, like the young patient who passed, have no one left to tell them.

'Into The Fire'

Dr. Aaron Browne is a physician at UMMC, and for most of 2020 he has lived in hell. He is a resident, a doctor in the final stage of training. The designation has placed his cohort on the front lines of the pandemic as it has ravaged Mississippi.

"Our ER is run by residents. Our hospital is run by residents. You often get four days a month off, max. You work weekends. You come in at 6 in the morning and see COVID until you leave at 7 at night," Browne says.

When he spoke to the Jackson Free Press in the first days of December, using a pseudonym, Browne mixed metaphors, fruitlessly searching for a way to describe the relentless struggle of the residents in a pandemic year.

"There's this undertone," he said. "Like worker bees thrown into the fire." There is no suitable poetic language for it. "We don't get hazard pay, or anything like that." He found a way to laugh, in spite of it all. "Actually, we're lucky we don't make enough to get a pay cut."

Others at UMMC did, with the hospital facing a sharp drop in revenue due to limitations on lucrative elective surgeries.

Every part of his work day exhausts the body and soul. In the mornings he sees his patients. "When it started we'd have one or two COVID patients that we were taking care of. Over the last couple of weeks, that's jumped up to half of our lists—six, seven of the patients we're taking care of," he said.

"You go in, you gown up in all the protective gear. You talk to them, try to provide the best care that you can. And their family can't come. So you're the line of communication."

Browne will never be able to share the private moments and intimate messages the virus forces him to relay, even as they linger in his mind. "There's a kind of emotion that passes between a patient and their family when they're sick," he says. "And now we're—us and nurses—tasked with being that emotional bridge. On the worst days of these people's lives."

"If you could pinpoint what's emotionally draining about all of this," Browne says, "that would be it."

Browne's long days inside the hospital are filled with grief manifested. But the moment he steps outside UMMC the repetitive indignity of disbelief confronts him. "You leave, and you can't even get home before you hear it on the radio," Browne says. "Downplaying what you just saw for the last 12-hour shift."

The new doctor is aware of the intense weight of the virus, pressing down upon him and his colleagues at every turn. "Suicide rates among physicians are incredibly high. Especially training physicians," he said. "Adding the increased stress of coronavirus onto that, plus the constant barrage of people acting like it doesn't exist." His voice trailed off.

"You have to be the mouthpiece for your friends, your family, people you don't even know. You have to convince them that it's real." He has tried that route, and even the glaringly obvious proximity he has to the catastrophe itself is not enough to sway many. "Eventually it just becomes too tiring. You have to learn to tune it out."

But he immediately acknowledges it is a poor remedy. "It keeps eating away at you," Browne said.

'So-Called Experts'

These stories have been a constant in the medical profession during the long months of coronavirus. Health-care workers are caught between two realities. One is the floating world of the hospital and the clinic: logical and antiseptic. Misgivings about the virus' immense danger wither here, buried between rows of the sick and the dying.

The second reality contains everything beyond the emergency-room doors. There, truth becomes a struggle of willpower, not reason. Across Mississippi, a crop of belligerent denialists assert falsehoods and conspiracies to the detriment of their own kinfolk. A north Mississippi mayor divides the deaths against the state's entire population and thus declares the crisis too minimal for the Stafford Act, a federal law that expands executive authority in emergencies. A clinic director downplays the December surge as a phantom of triple-counted tests.

"What a bunch of bullcrap," State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs raged at a Dec. 2 press event, pushed beyond his usual calm by another repetition of the debunked lie about inflated test numbers. "How many times do we have to tell people this? Quit buying into crazy nonsense!"

The misery apparent in the daily lives of frontline health-care workers shows in the fatigue of public-health leadership. There is only so much soothing they are capable of—the country's collective inability to join together and crush the virus seems more incomprehensible with every passing day.

Dobbs had a desperate plea for the state at a Dec. 4 press event. "What would you do to save a life? What would you do to save 1,000 lives?" He estimated that this might be the cost of the present surge in the span of only a month.

The timeline of an outbreak is set in stone. The health-care system is capable only of mitigating what failed policy and a general disregard for human life has caused. After infection, after hospitalization, comes death. The winter surge has already claimed enough lives to push Mississippi's official COVID-19 death toll above 4,000. And testimony from the state health officer indicates that the true number, based on excess deaths, is already above 5,000.

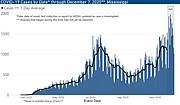

As of Dec. 8, skyrocketing transmission has driven the seven-day average of new cases to 1,931, higher than virtually any single day prior to December. The week after Thanksgiving was a dizzying rush of unprecedented growth, with over 2,000 cases reported three days in a row.

New hospitalizations—and especially the velocity with which they are arriving—are unlike anything seen in the pandemic in Mississippi so far. Over 1,100 Mississippians afflicted with COVID-19 crowd the state's hospitals, in a lurching upwards climb that has shown no signs of stopping.

"This wave is growing much more quickly than the summer surge (as predicted)," Dobbs tweeted on Dec. 8. "But our future is in our own hands."

And yet, after months of relative cooperation with the state's public-health establishment, Gov. Tate Reeves himself has joined the ranks of the skeptical as the crisis has reached its highest peaks.

It began in late November, as a unified chorus of public-health leaders begged him for a statewide mask mandate ahead of the Thanksgiving holiday. Reeves brushed their concerns off, refusing to expand the restrictions beyond the piecemeal county-level mandates that have proven insufficient to curtail the spread of the virus so far.

The governor declined even to plead with Mississippians to forego the upcoming family gatherings known to be conducive to mass transmission.

"I'm not gonna stand up here and tell you that you can't be with family," Reeves said. "Because each Mississippian has to make their own decisions."

The governor acknowledged that those decisions came with risks. But with so many choosing to take those risks, the oncoming surge has pressed Mississippi's hospital system against its limits and beyond them.

Reeves' hard break with medical expertise has grown beyond a difference of opinion—the governor has begun to use his position to belittle and deny the brutal realities of treating COVID patients in the middle of the surge.

When leadership from UMMC, the Mississippi State Medical Association, the Mississippi Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Pediatrics' Mississippi Chapter issued a joint statement calling for a statewide mask mandate on Nov. 24, the governor mischaracterized their plea for one measure among many others as a "silver bullet," doomed to failure. "I get frustrated when so-called experts decide that if we just did one more thing, that we could change this," Reeves complained when confronted with the letter on the same day.

Only a week later, with the Thanksgiving surge looming above the already overextended hospital system, Reeves again challenged the seriousness of the pandemic by undercutting UMMC's concerns about capacity in an interview on WAPT News.

"That particular institution has over 10,000 employees. Do you know how many patients they had in ICUs with COVID last week? Fourteen. ... I don't think that there are very many people in our state that believe that 14 patients with COVID in a hospital of that size and magnitude should have the kind of significant impact that it's having."

Every part of Reeves' conception of the problem is incorrect. As of the beginning of this week, over a fourth of all ICU patients at UMMC were suffering from COVID. Still, the majority of the severely ill coronavirus patients are in the medical-surgical floors, where a conscious decision to intubate patients at a later stage is leaving a massive burden for the med-surg floor to handle. And the inevitable seasonal crowding of the hospital has removed the limited runway the institution had in the summer.

Furthermore, "10,000 employees" refers to the entire UMMC presence across the state of Mississippi, including support staff, administrators, researchers, accountants, food service, among others. To suggest that this entire body of workers is capable of taking on the extremely technical project of treating COVID-19 is absurd.

A UMMC official confirmed to the Jackson Free Press on Dec. 8 that the hospital is presently at -27 beds, meaning almost 30 patients without proper placement.

Nineteen patients crowd the halls of the hospital, awaiting ICUs capable of handling their critical condition. Some of those are COVID patients. More await beds in the med-surg floors. The hospital is packed full, with transfer requests and surgeries backed up as more patients flood in.

These transfer requests represent the unspoken danger that has arrived with the new peak. It is not enough for UMMC to be operating at max capacity, instead of beyond it. UMMC, as Mississippi's only Level 1 trauma center, is a keystone in the state's entire health-care system.

Without UMMC's flexibility for transfers, and with other states equally maxed out on capacity, it is no longer hypothetical: the immense stress of COVID-19 will greatly harm patients needing care for completely unrelated conditions.

One More Day

Dr. Justin Turner, the CEO of TurnerCare, a Jackson internal medicine clinic, has emerged as an outspoken voice for the medical profession and his patients in the difficult days of the winter surge. In an interview, he acknowledged the pain and the emptiness of serving in a pandemic that has become a conduit for a metastasized political war.

"In April, when things were getting bad, I thought we'd lose some battles, but come together. Because that's what America does," Turner said. In December, that hope is fading. "At this point in history," he added, before a long pause, "we have forgotten who we are."

Turner knows the pain of loss. "My clinic experienced its first death from COVID in late July. And at that point my mental health took a very sharp decline." He follows the admission up quickly. "It's not that I've never experienced death in my clinic before. It was the straw that broke the camel's back, after all the time, the energy ... it felt as if those efforts were pointless, because we are fighting against a systemic mindset."

There, finally, arrives a metaphor suitable for this stage of the pandemic—the proverbial straw. One more patient gulping for oxygen in an overpacked emergency department. One more resident pushed over the brink by a surge without an end in sight. One more lie, one more conspiracy, one more crack in the communal reality that binds a society together.

For Watson and the nurses of 2 North, the only answer has been to look to each other. "What are you feeling? How are you treating your patients? How crazy is all this? Sometimes we're just there to make each other laugh in the middle of a very stressful shift," she said.

A moment of laughter. The support of a friend. A familiar bottle of perfume. Anything, with the weight of the world bearing down, to get through one more day.

Contributing reporter Julian Mills assisted with this report. Email state reporter Nick Judin at [email protected].