Tuesday, February 11, 2020

In recent years, Mississippi has increasingly favored large subgrantee organizations over individual recipients of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds. In the wake of alleged embezzlement of millions in TANF funds, Gov. Tate Reeves declined to say whether the state would rethink its funding priorities. Photo by Nick Judin

The State Auditor's office caused shock waves last week when it unveiled the largest case of alleged public embezzlement in Mississippi history, but the Jackson Free Press reported as far back as 2016 that then-Mississippi Department of Human Services Executive Director John Davis was not allocating $35 million in federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, funds to the poor people who were supposed to receive the money.

At the time, Davis argued that he had done all that he legally could to get TANF money to needy families, even with the additional funds left on the table.

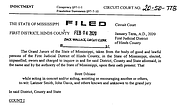

In the indictments, State Auditor Shad White and Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens accuse Davis of fraudulently diverting the public welfare funds through a series of educational nonprofits. They allege that defendants, including Mississippi Community Economic Center Executive Director Nancy New and former professional wrestler Brett DiBiase used diverted TANF funds to subsidize their own lifestyles. The Clarion-Ledger reported that DHS hired Brett DiBiase, paying him an annual salary of $95,000. The indictments allege that they laundered the money "through various fund transfers, fraudulent documents, at least one forged signature, and deceptive accounting measures."

The State is not allocating TANF funds to subgrantee organizations as the current investigation unfolds. Subgrantees like New's MCEC agree to use TANF funds in community development projects. Individuals may also apply for TANF funds, delivered as cash payments to underemployed or unemployed families with children.

Gov. Tate Reeves acknowledged to media last Thursday that DHS had ordered a near-total freeze on TANF distribution during the investigation of the alleged fraud. "We felt like the integrity of the TANF funds—and specifically the fact that they are almost exclusively federal funds—we had to get a handle on the use and the misuse of those funds," he said. Reeves, though, clarified that TANF funds for individual families were not subject to the freeze.

'Welfare Queen' Mythology

The State of Mississippi refusing to distribute money allocated to help the poor is not new. The Jackson Free Press reported in 2017 that the State has winnowed down TANF payments directly to needy Mississippians over the last decade, a trend that started when Republicans took over both houses of the Legislature back in 2012. Only 165 of the roughly 12,000 Mississippians who applied for TANF received it. The State denied thousands more.

A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities study revealed that, between 2001 and 2017, poor families with children in Mississippi receiving TANF cash assistance declined from 17 in 100 to six in 100. The State has argued in the past that no amount of funding could bridge that gap. In 2016, Davis publicly lamented the lack of funds in the face of the overwhelming need of impoverished children. ""We'll never have enough money to get people off the waiting list," he said.

Increasingly, restrictive spending on welfare has been a feature in state government, Senate Minority Leader Derrick Simmons, D-Greenville, said. "Over the years there has been a legislative disdain for assisting the most vulnerable populations in the state of Mississippi," he said in an interview.

The sudden smothering of individual welfare contributions is part of a much longer story, predating TANF itself. Originally, the program now known as TANF was Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC, a New Deal program created to support single mothers. Civil rights activists pursued legal challenges in the 1960s and 1970s to expand access to the program for black families. But broader access to the benefits came with a price: welfare opponents fabulized images of social parasites living large on the public dole, culminating in President Ronald Reagan's "welfare queen" mythologizing.

Before long, public policy toward the program reflected public fears that welfare bred complacency, and bit by bit states restricted the benefits through work requirements, prohibitions and extra complications. President Bill Clinton finally put AFDC out to pasture in 1996, replacing it with TANF. TANF is a block grant program, meaning states have much more flexibility in how they use the federal funds allocated to them.

Mississippians suffer from the stereotype of welfare dependence, Rep. Jarvis Dortch, D-Jackson, said. But in reality, he added, "we're the poorest state in the country. We have five of the most impoverished counties in the nation, and we aren't providing assistance to them."

From 2016: John Davis and MDHS' Dance with Privatization and TANF Funds

Reporter Arielle Dreher unpacked the reasons then-Mississippi Department of Human Services Director John Davis gave for not using TANF funds to help poor children.

Dortch says he questioned Davis personally, during the former DHS head's tenure, on TANF spending to assist Mississippians in poverty, but found few answers forthcoming. "There's no accountability for it. There are no reports for it," he told the Jackson Free Press.

Robbing Poor While Ignoring Rich Beneficiaries?

As the screws tightened in recent years on individual recipients of TANF funds, subgrantees like Nancy New's education center flourished, receiving tens of millions of public dollars with little to no apparent oversight. Last year, the state auditor's office found critical deficiencies in MDHS' monitoring of its large-scale beneficiaries. The report found significant failures to monitor the compliance of subgrantees' use of public funds in accordance with the law, and additional failures to submit even basic documentation on the recipients of grants and funds.

The day after the state auditor announced the arrests, the Jackson Free Press asked the governor if the news would change the State's policy toward individual recipients of TANF money.

"I can't comment as to whether or not there's a connection in terms of the percentage of individuals that have requested funds that have or have not received them," Reeves answered. "What I can tell you is that the auditor is continuing his investigation into the alleged actions of both former employees and grantees. As the picture becomes more clear, it may become easier for us to answer that question. But at this point, I can't do it."

Disclosure: Nick Judin attended New Summit School and in 2006 served as a production assistant on a project filmed at the school in partnership with MCEC.

Email state reporter Nick Judin at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter at @nickjudin.