Tuesday, February 16, 2021

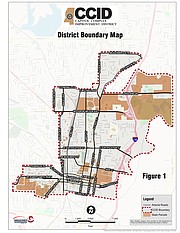

Mississippi Capitol Police originally patrolled the few blocks surrounding the Capitol building in downtown Jackson, but gained a larger area of jurisdiction in 2017 after the Legislature established the Capitol Complex Improvement District. If the bill becomes law, those arrested under misdemeanor charges starting May 1, 2021, in this area may be sent out of the county until they make bail or go to trial. Map courtesy MSDFA

Mississippi Capitol Police are set to gain lead jurisdiction in parts of Jackson, as well as the ability to eject those it arrests on misdemeanor charges out of Hinds County, if a bill that passed the Mississippi Senate last week becomes law. Senate Bill 2434, if successful, would move jurisdiction over parts of the city inside the entire Capitol Complex Improvement District from the Jackson Police Department to the special State police force.

Sen. Brice Wiggins, R-Pascagoula, says he authored the bill after watching the dust settle on the Jan. 6 storming of the United States Capitol.

“There was a question of who had primary jurisdiction,” Wiggins told the Jackson Free Press in a Feb. 5 interview. “Was it the U.S. Capitol Police? Was it D.C.? Was it Virginia? So what the bill does is it says if there is a question as jurisdiction then the Capitol Police would have primary say."

Wiggins says he wrote the legislation in order to prevent miscommunication at the Mississippi Capitol by placing the Capitol Police in the lead during any event that involves multiple agencies—namely the Jackson Police Department or the Hinds County Sheriff’s Office.

“I know from my experience in working in prosecutor's offices and in the court system that law-enforcement agencies can be very territorial,” Wiggins said. “And so that's what happened in the U.S. Capitol situation. He pointed to reports of jurisdictional questions, which led to the delay in the response. “And so we're trying to avoid that."

Capitol Police previously increased their presence around the Capitol the day after the events of Jan. 6 in Washington, D.C., though there were no reports of violent protest in Jackson.

The bill further streamlines Capitol Police by moving them from the Department of Finance and Administration to the Department of Public Safety, under the purview of Commissioner Sean Tindell. “After all, it is a public-safety agency, so we wanted to make sure that was going as efficiently as possible for public safety of the legislators, of the guests, of the staff, of everybody at the Capitol,” Wiggins said.

State Jurisdiction Over Crime, Arrests in Jackson

Lead jurisdiction for Capitol Police isn’t the only goal of the bill, however. It is also a way to involve state police more in a majority-Black capital city that has not always agreed with how state officials would police it. In particular, the Republican supermajority that runs state government can differ with capital-city officials, prosecutors, police, and citizens in the Democratic city over crime-fighting and detention, especially when it comes to non-violent misdemeanors.

To Wiggins, whose previous attempts to expand the state’s gang law have failed, his efforts are needed to please people in and outside the capital city who want to see more misdemeanor arrests, which are low-level offenses such as petty theft, prostitution, public intoxication, disorderly conduct, simple assault, or using or possessing marijuana.

“There's a frustration by people, including those in Jackson, that misdemeanor crimes are not being handled,” Wiggins said.

But before the crime-fighting bill could be put into action, there were two prominent flies in the ointment. The first is Jackson’s inability to house those charged with misdemeanors due to a federal consent decree—which Wiggins blamed on local Democratic officials. “The state wouldn't have to step up if it was being handled locally,” Wiggins told the Jackson Free Press. In a Feb. 3 debate on the floor of the Senate, Wiggins had more to say on the matter. “My understanding is next week right here in the State Capitol trials are going to be held for Hinds County because, quite honestly, Hinds County can't do their job,” he said.

The second problem facing Capitol Police was a lack of criminal-justice infrastructure. Capitol Police have held the jurisdiction to make arrests in the Capitol Complex Improvement District since 2017, but as Sen. Joey Fillingane, R-Sumrall, noted during the Feb. 3 debate, their capabilities have not always matched their authority.

“Do they have a Capitol Complex prosecutor?” Fillingane asked. “Is there a Capitol Complex judge or a Capitol Complex jailhouse even?”

“No, it doesn’t exist,” Wiggins replied.

The answer to these two problems lies in an extra subsection added to a committee substitute version of the bill, which became a singular point of contention during debate. The proposed language allowed Department of Public Safety Commissioner Sean Tindell, if he so chose, to enter into contracts with Madison and Rankin counties to essentially rent beds to to house those Capitol Police arrest and charge with misdemeanors.

Sen. Walter Michel, R-Madison, questioned the finances behind the bill. “We're going to allow the Department of Public Safety to cut deals with the sheriff of Madison County, or take bids on what a bed would cost per night to give a prisoner a warm bed and three meals?" he asked.

Wiggins replied: “It would be the normal course of what they do. I mean I think that stuff happens all the time, so I don't have any particulars about that."

Last October, Jackson allocated $500,000 to rent additional space for inmates in other counties. So far, Jackson has contracted with Yazoo County to house 25 inmates and Holmes County to house 12 inmates. Starting from Oct. 13, 2020, the contracts last one year. These beds cost the city of Jackson $25 per day, per bed for Yazoo County and $31 for Holmes County. Aside from a bed per inmate, the costs include health screening, blankets, clothing, food, and water. Over the course of their year-long contract, this adds up to $228,125 for the Yazoo contract and $135,780 for the Holmes contract for a year each, adding up to $360,905.

“The people are complaining that the misdemeanor cases are not being handled, and so it needs to be handled somewhere, and if it ain't being handled in Hinds County or in the city of Jackson then it needs to be handled somewhere,” Wiggins told the Jackson Free Press.

‘If It’s a Misdemeanor, You’re Not Entitled to a Jury’

With this revised bill, Wiggins could kill two birds with one bill. Capitol Police would be able to solve its lack of space and infrastructure at the same time—by sending those arrested out of Hinds County. These county contracts would see the State paying those counties to house those charged with misdemeanors. And, of course, those who want to see increased incarceration and criminal penalties for non-violent offices would consider the legislation a victory.

Many, though, including elected officials from the capital city, disagree.

“From whence will be drawn the jury of my peers?” Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson, asked Wiggins.

“Well, if it’s a misdemeanor, you’re not entitled to a jury,” Wiggins replied.

With that comment, the bill’s sponsor from the Gulf Coast inadvertently named one of the many concerns with misdemeanor arrests and subsequent jail time and costs—too little oversight over how they’re handled and who they can disparately affect: poor people of color.

University of Michigan Law School professor Eve Brensike Primus addressed this issue in 2012 in “Our Broken Misdemeanor Justice System: Its Problems and Some Potential Solutions.” She cites Harvard Law professor, and 2016 Guggenheim fellow, Alexandra Natapoff’s work on misdemeanors in the U.S., writing: “(Natapoff) rightly points out that legislative overcriminalization coupled with conflicting police responsibilities and vast police discretion has created a system in which poor people of color are routinely arrested for misdemeanor offenses even when there is little evidence to support their arrests.”

Due to poor legal representation available to most accused of non-violent misdemeanors, Primus and Natapoff write, many defendants end up pleading guilty to crimes they did not commit—which “leads to the conviction of countless innocent individuals, and contributes to the racialization of crime in America,” Primus writes.

Arrests and jail time for low-level, non-violent crimes can also have the opposite effect from reducing worse crime and violence. The 2016 BOTEC study of Jackson crime and violence, funded by the Mississippi Legislature, made it clear that police and jail contact for young people is one of the top precursors for committing more violent crime as they get older, urging other research-based options for reducing crime instead whenever possible.

Primus cites Natapoff’s suggestion for structural change, which is the exact opposite of what Wiggins is pushing for the majority-Black capital city: “make more misdemeanors nonarrestable, nonjailable offenses.”

“It would discourage police from using misdemeanor offenses for order-maintenance purposes, reduce jail populations, and remove some of the pressure that the system currently exerts on misdemeanor defendants to plead guilty,” the Michigan law professor writes before going on to offer additional misdemeanors reforms.

Police ‘Been Going Through Hell Lately’

Sen. Blount of Jackson decried the sudden appearance of the revision during Feb. 3 debate over the bill, noting that in speaking to them that morning, “the senators for Madison and Rankin don't know anything about it.” Blount explained how he had asked whether the senators were aware of whether their counties would even be willing to house more people in their jails, to which they replied, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out.”

Wiggins replied that these contracts are not mandated, but only an option. “All it's doing is saying it is authorizing for a contract to be entered into,” he said. “It does not mandate it, it does not require it, it is simply providing an option. So if Madison and Rankin County don't want to do it, they don't have to do it. It's authorizing the Capitol Police to enter into a contract.”

“If the bill that has been taken up today had been the bill that we had discussed and the bill that was originally introduced, we would have passed this thing unanimously in one minute,” Blount said. The original bill did not give Capitol Police extradition authority to house those charged with misdemeanors in other counties.

Sen. Chuck Younger, R-Columbus, defended Wiggins’ bill, which he helped craft. “What good is it going to do if Capitol Police arrest somebody, and Hinds County won't accept them?” he asked of Sen. John Hohrn, D-Jackson.

“All of our officers, they've been going through hell lately, and you know they're only human. Sometimes there's not good ones, sometimes there's real good ones,” Younger said.

In reply, Horhn said “I would say that if the problem is space in jails, then why don't we help Hinds County get more space for its jails?”

Horhn, who helped bring the mostly ignored BOTEC reports on Jackson crime into fruition, repeatedly questioned the new bill’s efficacy: “If the problem is it's misdemeanors not coming up for trial because there's a misdemeanor backlog, there doesn't appear to be a criminal justice backlog, then why don't we provide more resources to Hinds County to deal with this problem and not put the problem off onto another county to the east or another county to the north of here?”

In a Feb. 11 statement to the Jackson Free Press, Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba made it clear he opposes the bill.

“We strongly oppose SB 2434 which would allow individuals arrested within Jackson city limits to be taken outside Jackson’s jurisdiction for prosecution,” Lumumba said. “While we appreciate the Legislature’s concern about incidences of crime in the City of Jackson and its interest in providing assistance, we do not want to abridge the constitutional rights and entitlements of our residents.

“Instead, we ask that the Legislature work with us to provide funding to advance our law enforcement and prosecution efforts, and funding for technology to advance the Real Time Command Center.”

The irony is that the State of Mississippi is trying to usurp arrest and prosecution powers from Jackson and Hinds County during a time when Mayor Lumumba, the Jackson Police Department and the Hinds County Board of Supervisors have all agreed on increased surveillance, the need to rent jail space from other counties for misdemeanors, instituting a youth curfew and joining U.S. Mike Hurst in the federal Project EJECT, a policing effort designed to “eject” convicted Mississippi felons into federal prison outside Mississippi, far from their families.

The collaborating local, state and federal agencies announced Project EJECT in Jackson in December 2017. Since then, violence has increased dramatically in the capital city.

More Power to Arrest ‘Black Lives Matter’ Protesters?

The extradition revision also drew scrutiny from State Public Defender Andre de Gruy, who voiced his concerns to the Jackson Free Press in a Feb. 3 interview and previously pushed back on Sen. Wiggins’ efforts to expand the gang definition in Mississippi. “So essentially what that means is if there were say, just trying to think of something random, like Black Lives Matter gathering in front of the governor's mansion, and Capitol Police decided to make a bunch of arrests, they could do that,” de Gruy said.

“And essentially tell the Jackson Police Department to stand down, transport those people to Rankin and Madison County, and then they would be tried in Madison County or Rankin County and not in the city of Jackson or in either the Jackson municipal court or the Justice Court of Hinds County. It's just really odd to me that this is being proposed in our Legislature. So yeah, that does raise a few questions.”

In a Feb. 8 letter to all state representatives from Jackson, de Gruy elaborated on the problems of out-of-county detention and trial. “If this becomes law, people arrested in Jackson could be taken before judges in Madison and Rankin County for the setting of bail. These counties have an economic incentive to hold these people in jail. Not only will the cost of detention be paid by the state but if convicted any fines accessed would go to the county coffers,” de Gruy said.

Those who make bail would be able to return to Jackson and have their trial in-county, but for those who couldn’t afford bail, they could be stuck in a different county awaiting sentencing. “Our concern is for those who would not make bail,” de Gruy said. “These would be the poorest of the poor. They would certainly not be able to afford to hire an attorney to represent them.“

Third Amendment Passed Late in the Night

During that same Feb. 3 debate, Jackson Sens. Horhn, Blount and Hillman Frazier, all Democrats, put forth an amendment to delete the extradition subsection, while Sens. Horhn, Frazier, and Michel offered an amendment to repeal the entire bill. Neither amendment passed in the Senate.

Late that night, however, the Jackson delegation finally got an amendment passed to do away with the sticky subsection. Sen. Blount spoke with the Jackson Free Press this morning describing the process. “All of us in the Jackson delegation were united on this," Blount said.

The amendment changes two parts of the bill—first, it removes the option to hold trials in counties other than Hinds for those charged with misdemeanors in Jackson. “We all recognize and welcome the support of the capital police in helping us address our crime problems,” Blount continued. But we were concerned about this venue language, and we worked with the Senate chairman, and we were able to get it removed."

The second change opens housing contracts to all counties, and not just Madison and Rankin.

“The other person who did a lot of work on this was Senator Horhn. He spoke to our district attorney, the county prosecutor, the mayor, about the bill,” Blount said.

"Senator Horhn and Senator Michel talked to the mayor, and the mayor, as I understand it getting it from them, has talked to other counties to look for help with the fact that our jail is overcrowded and under a court decree,” Blount explained. “So we just felt like if there's a county that wants to help us with that, it shouldn't be limited."

The legislation as it stands after the amendment, however, is still fixated on what the Michigan law professor would call “our broken misdemeanor system. Primus calls for more federal civil rights investigations into misdemeanor systems and the decision-making by police and prosecutors, as well as the type of legislation that would root out abuse and discrimination.

Fewer arrests for misdemeanors would have a stronger effect than more, she argues. “State legislatures should consider removing some of the discretionary power that police currently have by decriminalizing many misdemeanor offenses and altering the definition of other offenses in ways that limit police discretion to determine when there is a violation,” Primus writes.

Email Reporting Fellow Julian Mills at [email protected]. Additional reporting by Donna Ladd. Also see jfp.ms/preventingviolence.

Additional Reading:

Read the 2016 BOTEC Analysis reports on crime and violence in Jackson, which the Mississippi Legislature funded, and then-Attorney General Jim Hood ordered:

Precursors of Crime in Jackson: Early Warning Indicators of Criminality