Tuesday, November 23, 2021

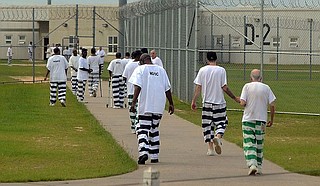

Parolees in Mississippi must pay a $55 monthly fee, which can become an added burden on those released from prison, respondents say. Photo courtesy MDOC

Simone Windom was waitressing at O’Charley’s Restaurant and Bar in Pearl, Miss., a few years back when she received a call that she had to spend the weekend at a halfway house located in Brandon because she had not paid $55 in monthly supervision fees as someone who was out of prison on parole. That happened to her a few times.

“I would literally be working, and I would just get a random call that says, ‘Because you didn’t make your monthly payments, the probation officer is requesting that you report to the halfway house; you need to report there at such and such time, and this is the time that you can leave.’ And that was that,” Windom recalled in a Wednesday, Nov. 17, interview with the Mississippi Free Press.

Windom said that her crime was stabbing someone who was attacking her pregnant sister in Madison, Wis., in 2013. She fled to Mississippi a year later and, after a few months, the Jackson Police Department flagged during a road check that she had a warrant out for her arrest.

After she spent three months in the Hinds County Detention Center in Jackson, the Mississippi Bail Fund Collective bailed Windom out. She later spent 18 months in prison for her crime. After her release, Windom had to be on parole for several months, and she paid $55 monthly to the Mississippi Department of Corrections as a parole fee.

In a phone interview with the Mississippi Free Press on Nov. 16, former City of Columbus Councilman Kamal Karriem related the story of his neighbor’s daughter. He did not reveal her name. She lived in Columbus, but ran to Florida in 2018 at age 25 after coming out of prison because she could not pay her supervision fee. She would eventually return in 2019, thinking the coast was clear.

“She didn’t have a job, and she could not pay her parole,” Karriem said. “And so she went on the run, and she went down to Florida.”

“And she thought things were alright and cool, and she came back home,” he added. “I don’t know if someone called (the authorities) or if they saw her, but they came and picked her up.”

Karriem’s neighbor’s daughter was initially in prison for two out of a four-year sentence for shoplifting. Therefore, apart from paying the parole fee, she had to pay restitution. “When she was released for two years of probation, she couldn’t get a job to pay (the parole fee),” he said. “So after about 90 days of nonpayment, they came looking for her.”

“And she hid, and then she ran, and she left, and then she came back,” he added. “And they arrested her, and they made her do the rest of that time.” She spent 13 more months in prison.

Karriem said that he knows another young lady who stole clothes to pay her parole fee.

“She would get up in the morning and walk through the shopping mall and steal shirts or anything that she could sell and come back down on the street and sell these items in order for her to meet her needs to pay her parole officer,” he said. He did not name the woman.

State Law on Paying Parole Fees

Mississippi Code § 47-7-49 creates the legal framework for paying the parole fee.

“Any offender on probation, parole, earned-release supervision, post-release supervision, earned probation or any other offender under the field supervision of the Community Services Division of the department shall pay to the department the sum of Fifty-five Dollars ($55.00) per month by certified check or money order unless a hardship waiver is granted,” the state law reads.

Fifty dollars goes into the Community Service Revolving Fund at the state treasury to fund the supervision program, $3 goes to the Crime Victims’ Compensation Fund and $2 to Training Revolving Fund for the prison training program.

“The offender may be imprisoned until the payments are made if the offender is financially able to make the payments and the court in the county where the offender resides so finds, subject to the limitations hereinafter set out,” the state law says. “The offender shall not be imprisoned if the offender is financially unable to make the payments and so states to the court in writing, under oath, and the court so finds.”

Marlow Stewart retired in August 2020 after spending 24 years with the Mississippi Department of Corrections parole section. Gov. Tate Reeves appointed him as a member of the Mississippi Parole Board beginning Nov. 1. In a Nov. 7 phone interview, Stewart told the Mississippi Free Press that everyone under supervision had to pay.

“They do have to pay unless they have what is considered a hardship waiver,” he said. “If you have a way that you can prove that to your agent and the court agrees to why you can’t pay your supervision fees, they petition the court to get a waiver.”

Stewart was a parole and probation officer for six years, 14 years as associate parole and probation officer, and two years as the regional director. He oversaw 19 counties and 130 staff before he retired.

He said that those on ankle monitors will pay more than $55. Stewart said before the prisoner leaves on parole, the individual appears before a government official for an assessment to determine the frequency of appearances before a parole officer and the amount to pay for a monthly fee.

“Based on your assessment before release, the parolee may have to appear weekly with a parole officer, monthly or quarterly, but regardless the payment is monthly,” Stewart said during the interview, “Ever since I’ve been working for the agency, they’ve been paying supervision fees.”

The punishment for nonpayment of the parole fee might include an appearance before a judge for possible reincarceration, he said.

Stewart said the Mississippi Department of Correction does not usually take a person back for a revocation of his freedom solely for failure to pay supervision fees.

“That’s not normally the case,” he said. “(But) if you have other violations with a failure to pay, you might be put back in prison.”

‘A Very Terrible Process’

Former Columbus Councilman Karriem, however, slammed the requirement to pay for supervision. As someone who spent eight years on parole, he had to pay $55 per month for that duration.

“Yeah, that’s a very terrible process because then it’s sort of like they used to have debtors’ prisons a long time ago in this country,” he said. “If you couldn’t pay your debts, they would throw you in prison.”

“And the courts abolished that because they said it was unconstitutional,” he added. “(In) this process here, you’re a victim of your own poverty. You can actually have done your time, get released for your good behavior, and then be penalized or even incarcerated again because of your inability to pay.”

Karriem said that the requirement to pay for incarceration drives people deeper into criminality. He knows many people on the run from their parole officers.

“They run all the time,” he said. “They run to be free, or either sell dope or participate in prostitution.”

“It drives a great segment of impoverished people, particularly people in the lower disadvantaged neighborhoods, into the underground economy,” he said. “And what I mean by that is selling dope, prostitution and doing illicit schemes.”

Karriem said that he knows several people who buy and sell illicit drugs to pay parole fees. “(They) go out and buy $50 worth of crack,” he said. “It’ll give you about five or six stones, and they’ll sell these stones for $20 each, enough for them to have a place to stay, get something to eat and pay that parole officer.”

Windom said in the Wednesday interview that when she had to be at the halfway house for nonpayment of a supervision fee, she had to arrange for some people to be with her kids for that weekend.

“If you missed the payment, there were three options—either you go to the (Hinds County) work center for the weekend, or you go to jail, or you go to a halfway house,” she said.

In a phone interview on Nov. 12, a law-enforcement officer, who asked to be unnamed in this article, recalled that while working at the Hinds County Detention Center some years ago, she booked people into the jail for nonpayment of supervision fees.

“It does happen,” she said. “It does happen for nonpayment, but a person has to be so far behind.”

“You have to understand that when a person gets paroled, it can be difficult for them to find work because of the crime, and a lot of people don’t want to hire them.”

‘I Don’t Think It’s Fair’

Mississippi Bail Fund Collective official Halima Olufemi said that requiring parolees to pay for supervision of their release condition puts them in a difficult situation.

“I don’t think it’s fair,” she told the Mississippi Free Press in an interview on Tuesday, Nov. 16. “Once someone has gone through whatever process, they’ve paid their debt to society, for lack of a better word. They are then able to be placed in a situation that makes you have to figure out, ‘Do I feed my family, or do I go in and pay this fee so that I can stay out of jail?’”

“I don’t think that people should ever have to be put in that type of situation,” she concluded.

Another official from the organization, William Sansing, who has worked with numerous people who have struggled with paying supervision fees, said in a phone interview on Nov. 16, that the situation imposes further punishment.

“And then if they don’t pay their fee, they’re subject to having their probation violated and then going back to prison,” he added. “I’ve seen it multiple times over the last 20 years.”

This story originally appeared in the Mississippi Free Press. The Mississippi Free Press is a statewide nonprofit news outlet that provides most of its stories free to other media outlets to republish. Write [email protected] for information.