Friday, January 14, 2022

Dr. LouAnn Woodward, vice chancellor and dean of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, held a press conference warning, yet again, of rapidly filling hospital capacity and an ongoing staff shortage. Photo by Nick Judin

Dr. LouAnn Woodward, vice chancellor and dean of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, addressed the media Tuesday in a press event both familiar and dire, another warning from the state’s flagship hospital in the depths of a wave of COVID-19.

“Welcome back to the party nobody wants to attend,” Woodward opened. “I wish I had some new answers for all of you. But the answers continue to be the same thing—to get vaccinated, to get a booster, to wear a mask. This new virus is very infectious.”

The surge has become severe enough, considering the latent damage to the state’s health-care system from nearly two years of pandemic care, that MSDH has restarted the mandatory rotation protocol that allows centralized diversion of high-severity cases.

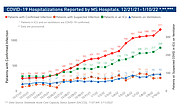

Omicron has now overtaken Mississippi, driving transmission to levels beyond imagining and possibly beyond the ability to accurately detect. The Mississippi State Department of Health announced 5,737 new cases of COVID-19 on Tuesday, right in line with the weekend’s 16,484 three-day total. Hospitalizations are on the rise as well, with 1,211 total patients across Mississippi with COVID-19.

“When the hospital is full,” Woodward warned, “whether all of the beds are taken, or all of the staffed beds are taken, the ultimate place that all the patients end up is the emergency department.”

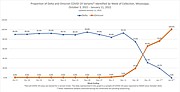

Toward the last days of 2021, providers worried about a dual surge—patients seriously ill with the delta variant and health-care workers out with omicron. But MSDH’s genomic sequencing has revealed that for Mississippi, the significantly more infectious omicron has outcompeted delta.

MSDH charts show the dizzying rise of the omicron variant. By this day in December, only 3% of sequenced cases were omicron. Today, omicron accounts for 100% of all examined infections.

Staffing Remains Bottleneck

Staffing shortages, even more than rising numbers, are plaguing the states’ hospitals, reducing bed availability beyond what physical infrastructure could otherwise support.

Dr. Alan Jones, UMMC’s vice chancellor for clinical affairs, explained the gap at yesterday’s press event. “In a normal state, before the pandemic, we may have 70 or so nursing openings across our system. We would shudder at that, say we’ve got to hire more nurses,” Jones said. “The attrition out of the workforce we’ve seen out of nurses … we’re faced with a nursing shortage (up to) 360 openings.”

Jones added that the temporary measures—incentives, internal transfers of nursing staff, for example—are no longer proving effective at backfilling openings. “(Nurses) at this point just say ‘I’m good, I’ve had enough. I’ll work my normal shifts but I can’t continue to work more,’” he said.

The nursing shortage, the most visible damage from a health-care system battered head to toe, is not a feature of any individual surge, and hospital leadership does not expect that number to replenish with the abatement of omicron or even the end of the pandemic itself. Jones anticipated a two- to three-year cycle before staff positions could be refilled.

At UMMC’s press event, health leadership confirmed that the omicron variant maintains the relatively lower virulence seen in earlier outbreaks across the world. But no relative comparison can deny the tidal wave of new cases and intensive-care shortages that plague the state as the omicron deluge continues.

In response, the Mississippi State Department of Health re-instituted a centralized system of hospital transfers for severely ill patients. This system was previously established in the delta surge when hospitals ran full with critically sick adults in need of intensive care.

“Due to the current wave of COVID-19, Mississippi has reached a point where hospitals can no longer accommodate acute clinical demands,” MSDH warned in its health alert. This new “focused ICU rotation” requires hospitals across Mississippi to report their ICU availability on a daily basis. Patients in need of higher tiers of care will be distributed to more substantial ICUs across the state.

Providers from rural hospitals have recently asked for such a system, warning that severely reduced capacity statewide has patients stuck in health-care settings unsuited for the severity of their conditions. Emergency-room caregivers have spent countless hours trying to find units willing to take them on. Now, MSDH’s order empowers MED-COM to evenly distribute these patients: alleviating some of the burden, but not increasing the overall capacity for care.

Omicron’s rampant infectiousness has increased the proportion of patients in hospitals with incidental infections—individuals hospitalized for reasons other than the virus. But Jones said the distinction was immaterial to the fact that overall capacity was declining, and a COVID-19 positive patient demanded the same effort from hospital staff.

“We have to take the same precautions, it’s the same extra work for our staff, it’s the same amount of (personal protective equipment) we’re burning through,” he explained.

The now-total dominance of omicron also provides challenges for therapeutic responses to COVID-19. Only certain forms of monoclonal antibody treatment work for the omicron variant, treatments with far more limited capacity than all forms combined.

This story originally appeared in the Mississippi Free Press. The Mississippi Free Press is a statewide nonprofit news outlet that provides most of its stories free to other media outlets to republish. Write [email protected] for information.