Wednesday, June 24, 2020

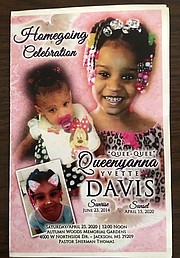

Queenyanna Davis would have been 6 years old on June 23, but she was murdered. She attended Watkins Elementary School in Jackson. Photo courtesy Davis Family

It was 9:30 p.m. on April 15, and Lukeitha Davis was getting ready to sleep in Wood Village Apartments in south Jackson. It was like any other night. She made a joke about her grandbaby, wore her night cloth and used the bathroom. As she was leaving the sparsely furnished living room for her bedroom in her low-income apartment complex, suddenly all hell broke loose.

"The next thing I heard gunshots. My brother was sitting right here, and my sister was lying down. I ducked and crawled right up to my room and laid on the floor," Davis told the Jackson Free Press later.

The gunshots startled her niece, 5-year-old Queenyanna Davis, who was there visiting with her mother, Elizabeth Davis. The little girl was sleeping on the living-room floor but jumped up at the sound of the booming sounds of the gunshots.

A bullet struck Queenyanna's head. But she was still breathing for some time afterward. Two medical emergency personnel came soon after Lukeitha's daughter called 911. An ambulance took Lukeitha's brother and another boy, also hit by bullets, away but left Queenyanna on the floor, bleeding, her aunt said. Another ambulance did not come for at least 90 minutes, Lukeitha Davis later told the Jackson Free Press.

"The ambulance came in about 11:30 p.m. or even midnight, and then they still waited. They didn't bring her out until the last minute," the aunt said.

"They said they could not move her, that they had to wait. I said 'wait for what?' That's my niece, take her to the hospital! So why do you have to wait one hour and 30 minutes to get my niece off the floor? She was bleeding, she was still alive," Davis said.

Queenyanna died in a pool of her blood right in the living room, her aunt told the Jackson Free Press.

That jump from the bed that night would be the last for the Watkins Elementary School kindergarten student. The school-loving girl left behind one sister and two brothers.

"That's my niece; she did nothing, why shoot her up, shoot my apartment when everybody was sleeping?" Lukeitha lamented.

Her own son Glen also told the Jackson Free Press that emergency workers delayed taking Queenyanna to the hospital. "She was still breathing," he said. "If they made it on time, they could have saved her."

An Ambulance Monopoly

Hinds County contracts with American Medical Response as its sole contractor for ambulance services. Jim Pollard, public affairs manager for AMR Central Mississippi, declined to provide the time that an AMR ambulance picked up Queenyanna Davis.

Instead, he emailed a statement to the Jackson Free Press stating: "We do not discuss matters under law enforcement investigation. Further, federal privacy laws prohibit our sharing patient condition or treatment. Our hearts are with all families who have lost loved ones to acts of violence. We prioritize trauma patients according to physician-approved protocols. When there are multiple patients, we send multiple ambulances."

JPD also declined to provide an incident report by press time.

Pollard did provide further information on AMR's services in Hinds County, saying it receives remuneration not from the county but from patients it serves, with the most significant portion of its income coming from Medicare and Medicaid clients with transportation needs. AMR operates in more than 40 states and the District of Columbia. "It is the largest company providing ground transport in the U.S.," Pollard said.

AMR is the largest ambulance provider in the country with outposts in most U.S. states. The company has changed ownership many times since its creation as a business to consolidate ambulance services in 1991. It is headquartered in Greenwood Village, Colo., and its current owner is privately held Global Medical Response, which also owns Rural Metro Fire, Air Evac Lifeteam, REACH Air Medical Services, Med-Trans Corporation, AirMed International and Guardian Flight.

Even as the company provides services to many urban and majority-Black cities like Jackson, the website indicates that GMR's leadership is all white.

AMR Central Mississippi serves the nine municipalities of Hinds County with a total population of 231,840, 16,002 in Smith County, 26,658 in Simpson, as well as 20,758 in Grenada County—more than 100 miles north of Jackson in north Mississippi.

Pollard informed the Jackson Free Press that the company operates 58 ambulances, and employs 128 emergency medical technicians and 97 paramedics spread across those four counties. It responded to 71,000 calls for ambulances in 2019. Global Medical Response owns AMR, including AMR Central MIssissippi. Five different AMR companies operate in 19 counties in Mississippi.

Under its contract with Hinds County, Pollard said ambulances must arrive within eight minutes, for 85 percent of priority-one calls—the ones judged to be related to the imminent loss of lives or disability—in Jackson and Clinton. The time increases to 12 minutes for Byram and 18 minutes for other locations in Hinds County, with fines leveled for noncompliance as indicated in the contract.

"When we entered into a new contract with the Hinds County government in 2016, we voluntarily increased the fine from $1,000 per whole percentage point below standard to $2,500 per whole percentage point below standard (85 percent)," Pollard wrote in a follow-up email to the Jackson Free Press. "We made that offer to the County, and the County accepted the offer."

Pollard points to exceptions to this rule. For example, if the company receives seven simultaneous priority-one calls, the eighth is viewed as outside its control. He said that the number of ambulances on the streets of Hinds County at any given time ranges from seven between midnight and 4 a.m. and 30 between 4 p.m and 5 p.m.

None is dedicated to Jackson alone. Pollard said drivers respond to different needs as they occur across Hinds County. They are not all situated in one place, but are spread out based on the prevalence of 911 medical emergency calls in different areas for previous weeks.

Scary Billing

The Better Business Bureau, with the stated goal of engendering trust between companies and people, did not accredit AMR as a national company. The bureau's website indicates that AMR has a pattern of complaints across the country, concerning billing or collection issues, and customer-service issues.

"Regarding billing or collection issues, consumers allege that the business continues to bill consumers, although the consumer or insurance has paid the bill," the BBB website states.

"Consumers also allege that the business sends late billing notices, or are delayed, and that the business does not work with the insurance that is provided to resolve billing issues. Lastly, consumers allege that the business does not provide efficient customer service when consumers contact the business to request information. That includes information that is inconsistent, and requested documentation is not provided."

AMR told BBB in response that "EMS has many processes that are challenging to understand that often can lead to consumer confusion and misinterpretations."

The company has a one-star rating on the BBB website, which is the average from 55 customer reviews and riffed with complaints of surprise billing.

One customer wrote on June 1: "Once you are 'helped' by them, the harassment begins. First, they may not contact your insurance provider but send you emails that the insurance was declined. The invoice would be outrageous—for a 20 minute (10 miles) ride for a non-serious condition (where I did not need support other than for saline water), I was charged over $1,100. And then they may quickly send the case to a collection agency (can they legally do that?!) after just ONE bill! Imagine riding on a vulture!"

Another customer complimented the emergency workers, but blasted the billing practices. "AMR EMTs were very good," the person wrote on May 18. "Billing appears fraudulent, inaccurate arithmetic, indecipherable billing layout, payments not delineated. Awful. I will contact our local hospital and ask them NOT to use their services."

Still another addressed billing on May 7: "The experience felt very much like they are systematically misrepresenting the payment situation from the patient and the insurance company to over-collect money, presumably thinking they will repay at some point down the line. Felt incredibly hostile, unprofessional and potentially illegal."

The size of the bill for an ambulance ride depends on the distance traveled and medical services rendered, Bruce Baxter, who runs a different EMS service, New Britain EMS, told courant.com in Hartford, Conn., which is only 13% white and has a 30.5% poverty rate, which is only slightly higher than Jackson's at 28.9%.

Baxter said the cost for people who can pay jumps up to make up for the losses incurred on calls from patients who cannot. Medicaid reimburses only a fraction of the cost of an ambulance ride, he said.

At press time, the Jackson Free Press is unclear the status of fines AMR might have paid in recent years for missing performance benchmarks. This reporter filed a public-record request with the county, and has not received a response.

However, AMR has been in the news in recent years across the county for fines it has paid for not meeting specific performance benchmarks.

In DeKalb County, Ga., in 2018, "AMR agreed to pay almost $600,000 in fines and nearly $1.3 million to increase service to help alleviate slow response times," 11alive.com reported.

The company paid fines and damages of $168,780 in 2014 and $212,200 in 2015 to the City of Spokane, Wash., where ambulance providers are allowed 10 minutes to respond.

"For every minute beyond 10 minutes, the fine is $60 per minute. For non-emergency calls, AMR has 20 minutes to respond, and the same late fees apply. AMR also faces fines if their on-time arrival rate for the month dips below 90 percent," KREM.com reported.

In its home state of Colorado, AMR paid $300,000 in penalties in 2017 to Colorado Springs and El Paso County for more than 4,200 instances in which ambulance crews failed to meet their required response times under separate contracts with the two governments.

"In February 2017, one crew surpassed the city's 12-minute limit by more than 43 minutes," The Gazette reported.

"In addition to the $300,000 in penalties, under its new contract, AMR has reimbursed the city $1.17 million each year for fire crews' time waiting for an ambulance."

Colorado Springs was one of the places that saw a bitter fight over privatizing ambulance services in the mid-1990s rather than keeping emergency transport as part of municipal services run through the local fire department. Privatization of ambulances there was a political battle over shrinking local government.

At the time, AMR was headquartered in Colorado, but owned by Laidlaw, the Canadian school-bus company, which later sold it. Detractors then accused the company then of cutting costs and increasing profits by reduced services and even sending pickup trucks out instead of ambulances in some cases.

Need for Speedy EMS

Bobby Gray, who lives on Holmes Avenue in northwest Jackson, said her nephew almost died because AMR did not show up when he went into a seizure. It was a few days after Queenyanna Davis died.

"We called them, and the fire truck came. He (nephew) was just flat out," Gray told the Jackson Free Press.

"They told the mother, 'well, just put him in your car and drive him to the hospital. We don't know whether the AMR is going to come or not.' They never did. He almost died."

An emergency doctor who has been working in Jackson for four years but prefers not to have his name in print told the Jackson Free Press that a true emergency is time-sensitive.

"So if you have a heart attack, you want to be seen, evaluated quickly, the same thing with stroke and gunshots," he said. "All those are very time-sensitive."

He said it is a big problem if a child is shot in the head, and there is any delay in the ambulance response. He posited that this happens because sometimes the hospitals are full.

"You have patients on a stretcher that cannot get into a room, and ambulances can't go on 911 calls. A lot of times that is the case. Those services are not available because they are spread so thin," the doctor said. He revealed that such situations are frustrating and that a lot of times, people who do not need to call 911 do so.

"They are taking services away from people that do need timely responses," he said. "For a sprained ankle, don't call 911. But it is a hard thing to navigate because a lot of people don't have rides to the hospital, and if they just want to come up to the hospital and be evaluated for their cough or something, then, how are they going to get up here? They just call the ambulance.

"I don't know. There is no easy fix to the problem, unfortunately."

The phenomenon of people calling ambulances because they have no other way is relevant when it comes to response times of ambulance services. Courant.com in Hartford, Conn., reports that for many, a visit to the emergency room by calling 911 is the only means of getting to hospitals for something like an ear ache in a city where one of every 3.3 residents live in poverty. The estimate is that between 25 and 45 percent of the people who call 911 for an ambulance have no other way to get to treatment for minor needs.

An increased number of non-emergency calls bogs down the system and puts those who need the service in danger as there is a delay in their emergency assistance. As the number of calls has increased, it affects response times, making it longer to arrive at a call, Steve Hansen, fire service chief in Racine, Wis., told the Journal Times.

The Jackson-based emergency doctor reacted to Queenyanna Davis' aunt's description of the event of her death and especially the delay in emergency response, saying that the emergency personnel might have treated it like a crime scene.

"You don't want to disturb any evidence with people who are coming in and out of a crime scene," he said.

Even though the rate of survival for someone with a gunshot to the head is 1 percent, he said, some people can be talking afterward.

Journal JAMA Surgery, a publication of the American Medical Association, reported in October 2017 that emergency-medical service units average seven minutes from the time of a 911 call to arrival on the scene. That median time increases to more than 14 minutes in rural settings, with nearly one of 10 encounters waiting for almost a half-hour for the arrival of EMS personnel.

"Longer EMS response times have been associated with worse outcomes in trauma patients. In some, albeit rare, emergent conditions (cardiopulmonary arrest, severe bleeding, and airway occlusion), even modest delays can be life-threatening," the journal says.

Would Queenyanna have survived with a better ambulance response? It is impossible to know. But she will not be resuming this fall with her classmates at Watkins Elementary School.

A message about her death is on the school's Facebook page.

"WE love you, Queenyanna Davis," it says.

She would have turned 6 on June 23, but her life and the promise it holds was cut short.

Email city/county reporter Kayode Crown at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @kayodecrown. Donna Ladd contributed historic information about the ambulance controversy in Colorado Springs in the 1990s.