Wednesday, August 4, 2021

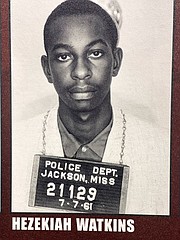

Hezekiah Watkins, now 73, landed in Parchman Prison in Mississippi at age 13 after trying to meet the Freedom Riders. Photo by Kayode Crown

Hezekiah Watkins was looking for a hero. As a 13-year-old middle schooler in 1961 in Jackson who had lost his father three years earlier, he thought that seeing and possibly touching a Freedom Rider would fulfill him.

U.S. Supreme Court rulings in 1949 and 1960 that racial segregation in interstate buses and route facilities was unconstitutional emboldened young Freedom Riders. In the summer of 1961, the mixed-race Riders braved severe beatings, imprisonment, maiming, and death from white mobs, supremacists, the Ku Klux Klan, and the government. They rode on interstate buses, trains and planes into southern states—Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana—stopping at various spots to integrate facilities and face arrest.

More than 400 Freedom Riders made the trip south, beginning on May 4, 1961. Twenty days later, they started a journey to Jackson, Miss. By the end of the summer, 328 ended in Mississippi’s Parchman Prison after police arrested them for “breach of peace” for moving into the segregated waiting areas of the bus stations.

On Saturday, July 10, Watkins, now 73 years old and a guide at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, met the Jackson Free Press inside the museum to talk about how he was arrested at such a young age.

How It Started

“My journey started on July 7, 1961, which was 60 years ago, I think Wednesday of this week, here in Jackson at the Greyhound Bus Station (at 239 N. Lamar St.),” Watkins said.

Before then, he had heard of the Freedom Riders, but he met a brick wall when he asked his teacher, mother and pastor about them. None of them wanted to say anything about it to the 13-year-old.

“I was interested in the Freedom Riders based on what I saw (happen) in Alabama on TV, and it became interesting to me seeing Blacks and whites work together, being beaten, all these types of inhumane things happening to them, and it just caught my attention,” Watkins said.

He and his friend checked the local news every day to keep up with the Freedom Riders and Alabama. “They eventually became our heroes and sheroes,” Watkins said. He did not name the friend.

“We thought they were just fighting against the police officers; we didn’t know their mission,” Watkins explained.

The Riders met violence as they reached the Deep South, with white mobs firebombing a bus in Anniston, Ala., beating Riders in Birmingham, attacking in Montgomery as police did nothing. Federal marshals were called in.

Watkins’ friend later informed him about a Freedom Riders’ meeting on July 7, 1961 at the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street. When they got there on their bicycles, the event was almost over.

“But the announcer was asking if there was anyone here who would like to join forces with the Freedom Riders? ‘If so, meet us at the Greyhound Bus Station,’” Watkins said as he related the story. “So I looked at my friend, my friend looked at me, and we both just nodded.”

The boys wanted to see what a Freedom Rider looks like, talked like, dressed like. “And if we’ve got an opportunity to reach out and touch one, man, you know, that’s glory,” Watkins said.

But they found downtown deserted. State authorities had already arrested the Riders and sent them to Parchman.

Two teenagers started goofing around at the bus station. “Being Black and you’re downtown, you don’t get a chance to enjoy downtown,” Watkins explained about the segregated capital city then. “You don’t get a chance to walk the sidewalk because if you walk on the sidewalk and a white person comes along, you have to step into the street. We didn’t have to do that because no one was down there,” Watkins said.

“So we—being 13-year-old kids—were really enjoying ourselves. There was a water fountain that read ‘White, Colored.’ We had never drunk from the ‘white’ fountain. We’ve been told that the water from the ‘white’ fountain was much colder, kind of had a better taste to it, and it was somewhat sweeter, and it reminded you of Kool-Aid.” They had their fill of the white-only water fountain and played with the water with no one around.

Then They Were Arrested

The teenagers went back to the bus station, and Watkins’ friend pushed him inside. They started laughing until a police officer grabbed Watkins on the shoulder.

“Why are you in here?” the officer asked Watkins.

“My friend out there pushed me in here,” he replied politely.

“What friend?” the officer asked.

“He’s out there,” Watkins replied.

The officer grabbed Watkins by the wrist and led him outside the bus station, and asked, “where?” Watkins looked left and right, but he could not find the friend, though the two bicycles were still there. His friend had run back home.

At the bus station, the officer asked Watkins his name and place of birth.

“It just so happened that my birthplace was in Milwaukee, Wisconsin,” Watkins told the Jackson Free Press. His father left for Wisconsin shortly before his birth; his mother returned with him after he died to be with her relations in Jackson.

Watkins tried to explain that he lived in Jackson. “He told me to shut up,” Watkins said. “At 13 years old, I was arrested and taken to Parchman prison and put on death row. Not only was I on death row, but I was put in a cell with two other inmates; those inmates had been tried for murder. They had been convicted, and they had been sentenced to die.”

Ross Barnett, the Mississippi governor in 1961, thought sending the Freedom Riders to Parchman would stop the movement, but it did not work.

‘Confined Creature’ at Age 19

Jackson resident Frederick Douglas Moore Clark Sr. was 19 at the time of his arrest in 1961 at Tri-State Trailways Station on West Capitol Street soon after Watkins’ arrest. He would eventually spend more than 40 days in Parchman. Clark told the Jackson Free Press of his experience on June 19, 2021, at a Black Voters Matter event at Tougaloo College.

Clark went to Georgia, where the Southern Christian Leadership Conference trained him in their non-violence principles in 1958: “I was indoctrinated in understanding the philosophy of direct action and peaceful, peaceful demonstration as Martin Luther King Jr. practiced.

Civil rights icons James Bevel and Diane Nash later sought him to desegregate the bus stations’ waiting rooms. He took 10 people with him to the Trailways station. He said those younger than 18 in his group did not go to prison.

“I had just turned 19. I went to prison, and we were placed on death row,” he said. “We stayed on death row for approximately 40 days where they tried to kill us—they cut our food in half, and they put out cold air on us at night.”

“The only things we had were Salvation Army shorts and shirts and nothing else,” he added. “They took all of our sheets and pillowcase, mattress and everything we had in our cell.”

Clark related how correctional officers beat them with sticks and locked 38 of them in a 6-feet-by-8-feet steel vault, where they could hardly breathe with the only ventilation coming from under the vault’s door. “So I called on the guards for four or five hours and got us out,” he said.

The others did not like that he cried for help because they were “not supposed to give in. I was breathing on the crack under the door, and I was able to call those people to get us out of there,” he said.

“We had to say, ‘yes sir’ to get out of there,” Clark added.

After getting out of jail, he could barely walk and suffered health problems. “When I got out, it took me two months to be able to walk the streets because we hadn’t been walking; we were just confined creatures,” he stated. “All of us got pneumonia. I had double pneumonia, both lungs.”

“I was glad to get out, very glad to get out,” Clark added.

How Watkins Got Out

Watkins said he was at the prison for five days, which he felt was as long as five months. “And here I am in the midst of these two (he paused)—am just going to say two brothers—who gave me the blues at 13 things that I had to go through being in jail with them,” he said, sighing heavily.

Watkins remembers Gov. Barnett, who died in 1987: “Ross Barnett was the most racist person, in my opinion.”

“He hated all Blacks. And he hated poor whites. I can recall him being on television or radio uttering these words: ‘If you are white and you’re poor, ain’t got nothing for you because that’s your fault. And if you’re Black, I surely don’t have nothing for you,’” Watkins said.

“And during the sixties, Parchman prison was the worst prison in these United States,” he added. “It was still being run as a slave camp; you were working, people were being beaten. All of these things are still happening. I’m told that the governor wanted to send a message to the Freedom Riders, and that message was, ‘if you come to Mississippi, this is the type of treatment you’re going to get.’”

Watkins believed Barnett asked for him to be released after President John F. Kennedy called him. “I’m told that the governor made a call to the prison for my release, and I was released and brought back to Jackson,” he said. “They called my mother to come pick me up.”

Before then, his mother thought her young son was dead, having not seen him for days after spending much effort to search for him. “I’m told that when she received a call from the Jackson Police Department … she thought she was going to identify my remains.”

When his mother came into the jail, Watkins, with bruises, was in handcuffs standing against the wall at the back of the room. She jumped over desks and chairs in Fa flash and hugged him tightly.

“And since I couldn’t do anything because I’m handcuffed behind my back, we fell to the floor, and we both were crying and just enjoying each other.”

One day, after school later that year in September, Bevel sought out Watkins. Under his tutelage, Watkins participated in various protests for the next six years, starting with picketing the A&P Grocery Store in west Jackson and forcing the manager to employ Black people. He went to various counties for such civil rights work and was beaten, jailed and shot.

“I was the youngest person arrested at 13, and I had the most arrests at 109, so they say. To be honest with you, it could have been 110, maybe 99, I don’t know.”

“It was a good run. I’m 73 as we speak. Ask me, could I do it again? The answer is yes. I can do everything except Parchman prison. Never, ever want to go there again. I wouldn’t wish that on my greatest enemy.”

Email story tips to city/county reporter Kayode Crown at [email protected]. You can also follow him on Twitter at @kayodecrown.